Joshua Gordon is returning to love

Words: Carla Jenkins

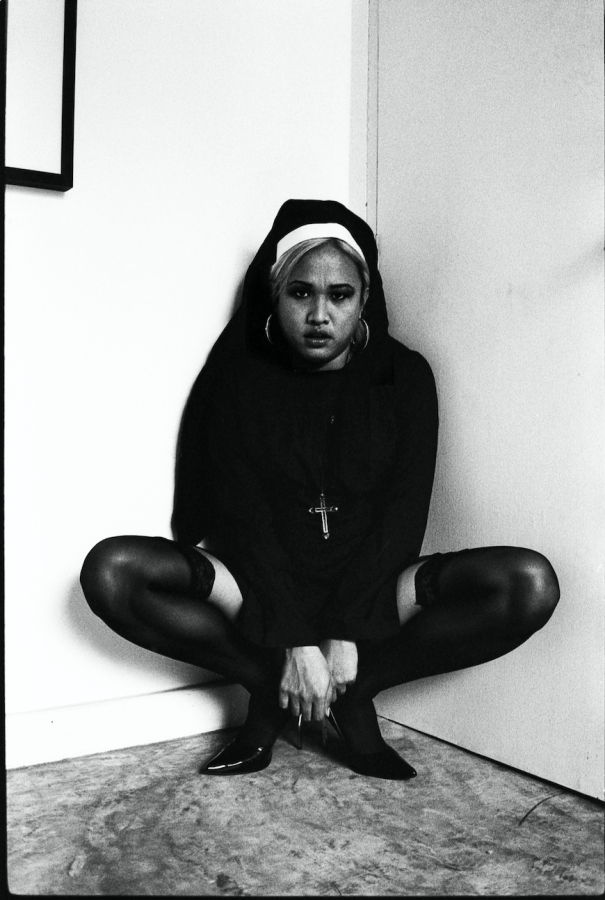

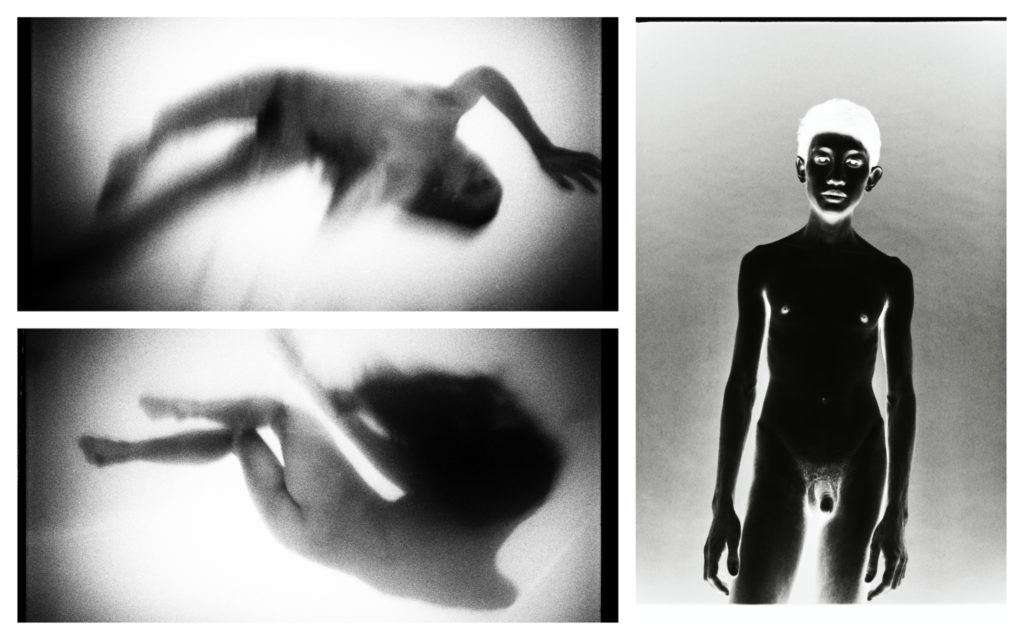

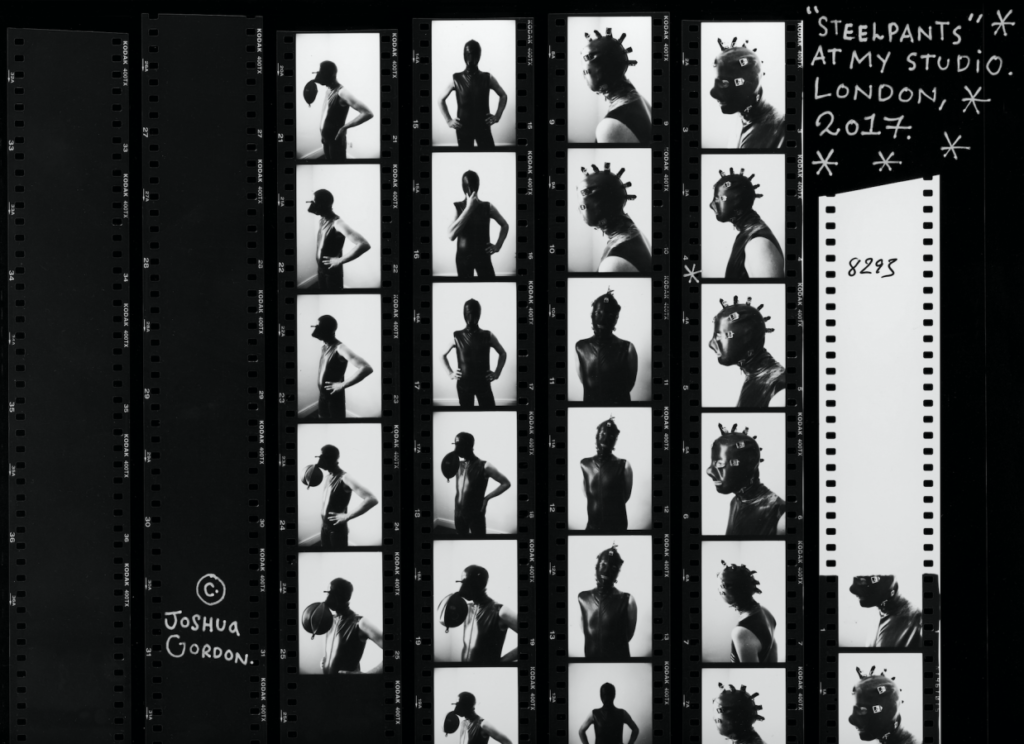

Photography: Joshua Gordon

Joshua Gordon’s latest film, ‘The Wicked Shit’, was published with NOWNESS in September. It’s a veritable visual feast of colours and sights as Juggalos come together for their annual gathering in Ohio. Gordon captures scenes of bare-knuckle fighting and smoke tricks alongside tender moments between people who, as a group, the FBI have classified as a ‘gang’.

Words always come with attributed meaning, and as time progresses there are certain words that are signifiers of a greater purpose, belonging or characteristic.

Take the word ‘gang’, officially defined as an “organised group of criminals”. Or, the word ‘subculture’, “a cultural group within a larger culture, often having beliefs or interests at variance with those of the larger culture”. ‘Communities’ are defined as “a group of people living in the same place or having a particular characteristic in common”.

So far, so good. They’re all similar and simultaneously different. Small groups within bigger groups, jarring ways of thinking and being. What if we flip it the other way; what associations come with the words ‘bikers’, ‘dominatrix’, ‘Grenfell’ or ‘Calais’?

This is where Joshua Gordon’s work comes in: it encompasses all of those words. A London-based, Dublin-native artist, Gordon’s work spans a variety of platforms, from film and documentary-making to photography and publishing. ‘Krahang’, Gordon’s portrait of young bikers in Thailand which dropped on Dazed, was sold with an accompanying photobook and audio mix, all neatly streamlined onto one little USB. To Gordon, though, the vessel in which his art is showcased through isn’t the most important part – it’s the idea.

“The mediums just tie everything together,” he tells me. “I love working with film as there are so many different elements; the sound, visuals, edit, grade, titles… There’s so much scope for being creative. Films move me, a photo- graph has never had such a profound effect on me.”

While Banksy’s ‘Girl With Balloon’ was shredding itself in another part of London, highlighting the absurdity of how we place economic value on art, Gordon was working on a project in Calais. Art, right now, is in flux. In today’s economic landscape, where everything seems to have a purpose or a place, there is a debate about where contemporary art fits. Is its rightful place among those who can pay millions for it? If so, is that arts failure? The incident of that self-shredding painting shows just how hyper-aware artists are about these questions. Deliberately or not, Gordon’s work suggests this too. It fits — not because it gives us answers, but because it poses more questions and that is exactly what art is meant to do. Is the importance or power of art being stifled by the increasingly warming capitalist Western climate? What is its purpose? Who holds the power, once a piece has been made? Is art being choked at the root, or the surface?

Described as an “obsessive documentarian of extreme communities”, marked with a fascination of “subcultures”, Gordon’s work treads carefully along already blurred boundaries, muddying the simple differences between the definitions of communities, subcultures, and gangs. He tells me that it’s been “close to a decade of trying things, failing, then trying different things”, and indeed it would seem that his perseverance is paying off. His work has won him collaborations with Saint Laurent and collectives Somesuch and NOWNESS. This year, he made the Dazed 100 – the definitive ‘cool list’ and even swung a modelling stint for Vivienne Westwood alongside his girlfriend, Jess Maybury, in Westwood’s ‘Youth is Revolting’ campaign. He assures me, however, that this is simply a means to an end.

“I don’t really care about that stuff, all I want to do is make films and photo projects. If some- thing happens around that to help me get fund- ing to do more similar work, then great, but fuck everything else. I’m here for one reason.”

And that reason yields a million possibilities. As ‘The Wicked Shit’ follows the Juggalos, ‘Krahang’ does the same with Thai bikers.

His film ‘Vertex’, made for Saint Laurent SS18, was to accompany a show that “celebrated young outsiders” and featured dominatrixes, Bangkok sex workers and Berlin street culture, all viewed by a (presumably) hedonistically-reckless-in-love couple on a night out. “Late Night, City Lights” by way of description.

There are some Gordanian characteristics that are inherent within all his work. The narration of all his films is internal; left to be told by the characters, or people on screen.

“I don’t know what else I’d be shooting if not these people. These subcultures I work with are interesting and I connect with them,” Gordon explains. “I’ve always been interested in communities like this, and the films and books that portray these characters.”

Creating work that does indeed focus on groups of people separate from the status quo, Gordon portrays his subjects with an air of observant indifference. There is no particular angle taken nor judgement passed over the people he films.

“They’re wild kids, what’s not to love?” is Gordon’s response when I ask him what initially drew him towards filming the bikers, in ‘Krahang’. The film captures that sense of wild hedonism that the boys chase in their daily life. The subjects talk about the thrill of the danger in riding their bikes, the smokes, the drugs, the parties, the girls…

“They’re young, classically cool guys, who race their bikes on the highway and shoot their enemies.”

It’s amazing how a particular narrative frame can shape our perceptions. As the rescue worker from Pedkasame Charity describes how people within the community describe the boys as Thai society’s “junk”, when you look at the boys through Gordon’s lens of “classically cool guys”, you see a sense of ease in their approach to life that’s missing from the Saint Laurent couple, no matter how hard they and the stylists try to capture it. And it’s an ease that Gordon picked up on too.

“The press I got around the film kept pushing how the boys were using their bikes to escape poverty, but that’s just not true. Their quality of life was amazing. A good time in Thailand is accessible to most, not just the middle and the upper class. They told me they loved their lives and surroundings. Every day they ate good, they worked hard and made money doing their little hustles and they had enough cash left over to get stoned and go fishing whenever they wanted. They all had jobs and made coin. It really pissed me off that people kept focusing on the poverty aspect of things.”

Of course it irritated Gordon — the consumer was instilling a narrative on these guys that was simply absent when Gordon himself was a chameleonic, temporary member of the group. There is a protectiveness over the boys, and Gordon’s work does seem laced with a sense of tenderness that could so often be either missed or misunderstood.

Gordon shoots Arm talking about his friend George who died in an accident and we watch as he takes care of George’s daughter like one of his own. Natt is filmed holding a kitten while his brother plays games on his phone; school is hard and fights are tough. Some things are the same wherever you go.

Regardless of who he shoots or the manner in which he shoots them, there is something special about Gordon too. He tells me that ‘Krahang’ is “just a portrait of the boys I met. There’s no deeper meaning”. Okay. Except, in withholding any imposition of narrative or projection upon the film, Gordon allows for the space to give these perhaps misunderstood communities a voice, however fleeting it may be. Surely there is some greater meaning within that?

For Gordon, the meaning is the way in which the work adds to his own life. It gives him a reason to exist, colouring in the corners until the next project comes along.

“Making stuff gives me a purpose, and a sense of fulfilment. When I’m not making things, or planning a shoot or film, I’m depressed, and I don’t know what to do with my time or my thoughts. The fulfilment is fleeting; as the projects end, so does my feeling of usefulness.”

His work takes up quite a lot of headspace. Gordon tells me that one of the reasons his artistic platforms stretched out to publishing was because he was “sick of sitting on old projects and wanted to get them out of my head so I could focus on new stuff”.

It seems like nothing goes to waste. Of future plans there are many, and I get the impression that we are only getting the half of it. Gordon is currently in Calais, and his next projects include multi-platform collaborations with his girlfriend, Jess Maybury, and one of hip hop’s most exciting artists, Rejjie Snow.

“I try to work only with people I know personally, in all projects I do. It makes me comfortable, just to do what- ever, and it’s also easy to discuss projects and concepts when it’s with someone you’re just lying in bed with.”

Whilst Gordon is referring to his partner and not Rejjie Snow here, in a non-committal disclosure, Gordon suggests that we can continue to look forward to that collaboration too.

“Me and [Rejjie] are both pretty busy and he said he wants to sit on it for a little while… We’ll probably keep shooting towards it until we’re both ready.”

Gordon working with the Dublin rapper is an interesting nod towards his roots — which start back in Dublin, and are something I’m keen to talk to him about. In almost every piece of writing about him, it is mentioned that though he is London-based, he is Irish born. Yet, there seems to be no more elaboration on that subject. I wanted to know whether this was because his Irish roots are of little importance, or if it was an avoidance that ran deeper.

“I’m proud to be Irish and I think it’s a big part of my character, but I have a weird relationship with Dublin. I was a different person when I lived there and made a lot of mistakes… I was a bad person in Ireland and made a lot of enemies. I had a lot of trouble and was getting mixed up in stuff I shouldn’t have been doing. So when I think about Dublin, my association with the place isn’t always positive.”

This answer gives a greater insight to how well Gordon managed to slot in with the bikers in ‘Krahang’ and the Juggalos in ‘The Wicked Shit’. Not, as first assumed, because of the ‘gang’s’ association with the darker spheres of crime, but because behind this answer is both an identification of community, and an urge to leave that community behind. The bikers and the Juggalos may feel a sense of belonging, but it’s perhaps that same belonging that Gordon wants to shake off.

“I left Dublin to leave Dublin itself, but also the Dublin mentality. A lot of Irish people move away and surround themselves with Irish people and nothing changes. I never wanted to be like that. I’m consciously trying not to think about Dublin all the time, as I want to focus on my new life, not my old one.”

I wondered what would happen if Gordon had remained in Dublin. Everyone knows that London, while a home of creativity, can be overwhelming in its nature.

There are boundless opportunities, but there’s always the prospect of being caught up, or lost within, the vastness of those opportunities. Some of Gordon’s best photographs are those of the billowing structures of Grenfell, or the stills of King Krule, who’s music, for many, is a soundtrack to London as a city. Songs like ‘Cementality’ talk of the “concrete bed” and the “soothing pavements”, noting the homely yet harsh city. One that can forgive a multitude of sins. On the flip-side then, is the horror of tragedies like Grenfell.

Despite the downsides, it seems like London is a better fit for Gordon.

“I think I always just needed to get away and start a new life. I would have been consumed by all of the negative stuff that was happening at the time around me.”

Does that mean that Dublin will never feature in his work?

“I’ll come back to Dublin to do a film about the way I grew up there and all of the madness I encountered, but the time isn’t right just yet.”

In that case, it seems like it might be a while. But when it does come, we know at least, it’ll be beautiful.