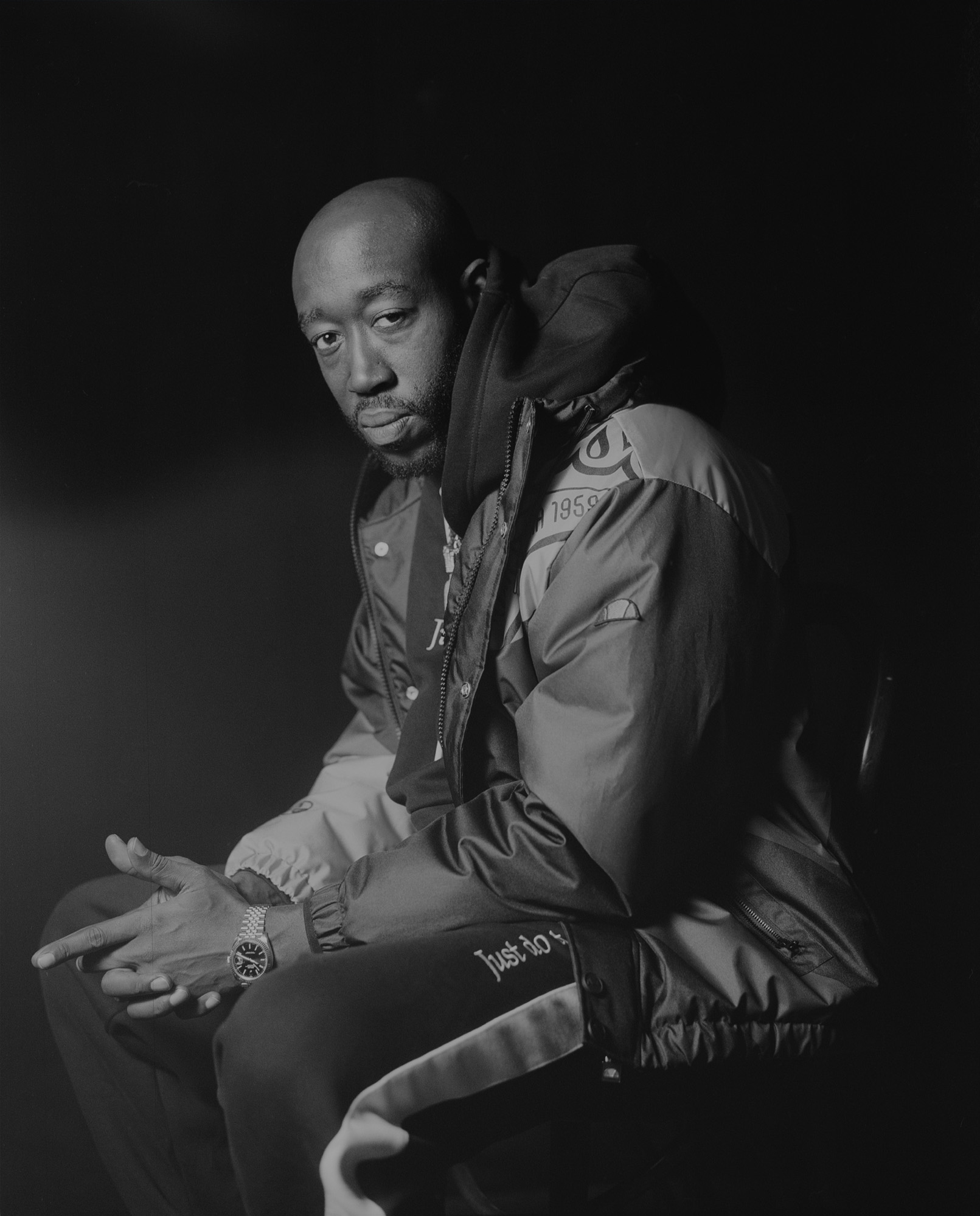

Freddie Gibbs: America’s Most Complete Rapper

Words: Dean Van Nguyen

Photography: George Voronov

For Issue 007 Dean Van Nguyen spoke to Indiana’s Freddie Gibbs. Dropping hardened street tales for the guts of a decade Gangsta Gibbs is hip hop’s most consistent spitter. The pair talked about his recipe for success and Freddie explained how to maintain relevancy once you reach the top.

Last autumn was cherished time for a certain strand of music geek hell-bent on ensuring their end-of-decade lists were as meticulously constructed as a Christophe Claret timepiece. Meeting Freddie Gibbs before his October 2019 gig at The Button Factory, Dublin, I figured I’d let him know about the crucial decision I had recently reached: the project that sat at the top of my best albums of the 2010s list was Gibbs’ underrated street rap masterpiece, Baby Face Killah.

“That’s one of the best projects I ever made,” he beamed. “A lot of my projects got slept on because they weren’t put out on major labels like Meek Mill, J Cole, Big Sean, Wiz Khalifa. Guys like that have had a head start when it comes to commercial success on me. Me being so stubborn – not stubborn, smart – I always went against the grain and went against the major label system. And now, I’m kinda getting accepted by them. They treat me like I’m a fucking new artist and I’ve been doing this shit ten years.”

Gibbs absolutely rates himself. “This decade I’m definitely one of the top five rappers, for sure,” he told me. “I think a lot of that shit got slept on: BFK is a classic, even Cold Day in Hell was dope.” In a more recent interview with legendary rap scribe kris ex for XXL, Gibbs (correctly) declared himself one of the greatest rappers of all time. Yet my deep love of Baby Face Killah seemed to genuinely enthuse him. Gibbs brought it back up after our interview had wrapped, a huge smile etched across his features. That delight was perhaps evidence that he still doesn’t always get all due credit.

“I think I’ve been very consistent since 2010,” Gibbs had told me. “I feel that was when I honed my skill together and got it all together. The scary part of this shit is I keep getting better as a rapper. I think on every project I get better. I’m learning new things musically. I’m trying different things lyrically. So, as long as I don’t lose my mind, I think I can make good music for years to come.”

In hindsight, Freddie Gibbs looked destined to be the rapper of the decade when he dropped ‘National Anthem (Fuck The World)’, an autobiographical tale of urban hardships and hard-earned ascent, back in 2010. The title teased patriotism – national anthems are, after all, intended to eulogize a nation. But within the parentheses of the title is the rejection of loyalty to any piece of land. “Fuck the world!” shouts Gibbs over producer LA Riot’s somber, string-drenched beat. Hard living has sharpened his view of the desperation that plagues the dominant species on this doomed planet. The personal nature of ‘National Anthem (Fuck The World)’ makes it feel like his origin story. When I make mixes of Freddie’s stuff, this is always track 1.

From there, Gibbs relentlessly found fresh angles. There’s the Blaxploitation snap of the Madlib-helmed masterworks Piñata and Bandana, the blurry noir of Shadow of a Doubt, the open-book writing of You Only Live 2wice, and the battering trap sounds of Freddie. One moment, Gibbs is rapping harder than anyone on the planet (songs such as ‘Still Livin’, ‘Paper’), the next he’s slowing his voice to a lurid crawl (‘Kush Cloud’), the next he’s dropping garbled auto-tune numbers that sound like time has just stopped (‘Basketball Wives,’ ‘Phone Lit’). Hip-hop in the 2010s was full of fractured ideologies and Gibbs was the closest thing we had to a unifier of all factions.

I always went against the grain and went against the major label system. And now, I’m kinda getting accepted by them. They treat me like I’m a fucking new artist and I’ve been doing this shit ten years.”

Freddie Gibbs

With a similar gruffness to his flow, Gibbs has regularly been compared to 2pac over the years. Yet by the time his career was in full-flow, Gibbs was already older than Pac was at the time of the legend’s death, and the precision of his bars and contemplative nature of his disclosures are those of a soul who has spent a long time grappling with the world.

“I think all my writing is pretty much personal. Actually, the most personal I got was on Bandana,” said Gibbs, ensuring our conversation came to the project he was promoting at the time. It’s an interesting assertion given the cinematic nature of both the music and writing that distinguishes his Madlib collaborations. “On songs like ‘Practice’ I was talking about inside my home life, things of that nature. But all the music is personal. That’s how I look at it and I just try to always stick to being me. I’m never out of character no matter what producer I work with. I think I’m versatile because of all the different types of tracks I can rap on. But I think that for the most part, no matter the producer, no matter the album, every song is personal.”

Pinata was released in 2014 and was immediately hailed as a classic, particularly among hip-hop purists attracted to Madlib’s usual wax-skinning production style and Gibbs’ classically lyrical approach. To drop the sequel five years later felt inspired, if not always inevitable. “Madlib is Madlib, he’s the most elusive person in music,” said Gibbs. “If you could find him good luck. For me to track him down – the first part of making an album with him is tracking him down. Once I track him down and then get him to sit still for a couple days, then I can make the album.”

Gibbs describes himself as a nomad, spending plenty of his career in California, New York or wherever else the work has taken him. He believes his various odysseys have given him a well-rounded sound. He’s also become closely associated with Alchemist, who helmed the 2018 record Fetti (a joint album with Curren$y) and the recent Alfredo. “Alchemist, he’s elusive too, but I know where he’s at – I know where his studio is at in LA – so all I really got to do is pull up on him,” revealed Gibbs. “I get my young homies to help me figure out what’s the new way things are, and I’ve got guys like Alchemist to educate me on things of the past. I’ve got a full spectrum.”

Gibbs hails from Gary, Indiana, and despite his travels, the city often serves as the backdrop to his music. In cultural terms, Gary is best known as the birthplace of The Jacksons. That musical dynasty aside, it’s one of America’s most desperate cities – a vision of decay severely impacted by the decline of the steel industry – and those that operated within its embryonic rap scene have struggled to gain mainstream traction.

“Because I had very few examples of original Gary music, the type of music that I could make, being from Gary, I had to set that example. I had to be the pioneer,” Gibbs said. “Now, there were guys before me that were rapping but nobody took it to the level I took it to. Now I looked at a lot of those guys and it’s always cheaper to learn from other people’s mistakes. So I saw the things that they did wrong and I didn’t go down that path.”

As for the city’s broader concerns, Gibbs probably doesn’t hold out much hope that the forthcoming presidential election will deliver any relief. “Trump, Obama, Bush, Regan, Clinton, whoever the fuck. All the last like six niggas that was president, Gary’s been the fucking same,” he told me just over a year out from the 2020 presidential election. “[It doesn’t] really matter to me who the president is. Jesus Christ could be the president, Gary is still in economic decline to this day. So I don’t really give a fuck about Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders, none of these niggas. Kamala [Harris], I don’t give a fuck about none of that shit. It’s really the politicians at the local level that you should really focus on. All this presidential shit is lies, propaganda, and all that bullshit. I try to focus on the guys who can directly help my community and just go from there. I try not to get all up in that voting shit, Vote or Die, all of that. I don’t really give a fuck about that shit.”

That doesn’t mean Gibbs simply stalks the sidelines. As the battle for America’s soul rages through every societal layer, he’s delivering unvarnished depictions of life in a city like Gary. Since our interview, he’s inked a deal with Warner Records. So into another decade, Gibbs, now a veteran, is focused on making his next batch of classics, and feels his powers are growing stronger.

A lot of guys fall off because they don’t know how to evolve. They don’t know how to evolve into the next way – the music changes every day.

Freddie Gibbs

“Our generation is getting better,” he said. “I know guys, no disrespect to them, a lot of guys fall off because they don’t know how to evolve. They don’t know how to evolve into the next way – the music changes every day. Nowadays, especially with the social media era, you’ve got to remain relevant. If you don’t remain relevant it can be over in a minute. And I’m not just saying older rappers become irrelevant, because there are rappers [who were relevant] last year who are irrelevant now.

“It’s just about how you maintain and a lot of guys don’t know to maintain. After BFK, you didn’t have to hear from me no more. But it’s a grind.”