What young people in the climate crisis really need

Image: Unsplash

Image: Unsplash

What young people in the climate crisis really need

Words: Ellen Kenny

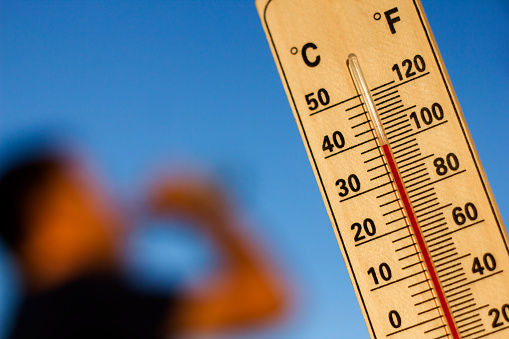

The current weather probably has you feeling lots of things: sweaty, itchy, and full of existential dread over the increasingly chaotic climate crisis across the world.

Climate anxiety is an increasingly common phenomenon, especially among young adults. A survey of 10,000 16 to 25 year olds across the world found that 84 per cent of young people are at least “moderately worried” about climate change. 58 per cent think that humanity is simply “doomed”.

45 per cent of young adults said that climate anxiety is negatively affecting their daily functioning. While the effects of climate change will likely have the gravest consequences outside Europe and North America, it doesn’t erase the very real concerns of young people in Ireland.

Their hopelessness is no surprise. The generations coming into adulthood were born into a crisis that is only deepening by the day. And, for as little that world leaders are reversing climate change, they’re doing even less to alleviate mental health problems.

The most obvious way to treat climate anxiety is to treat climate change itself in the countries it’s needed most. Young people can also exert whatever control they have over the situation by protesting and consuming sustainably.

If we want to pare down, though, new policies are needed to improve the day-to-day living of young people in the climate crisis.

Of course, policy issues like working conditions and public transport are slim pickings compared to the larger global crises happening. But if the Government has the chance to help young people overcome problems that young people themselves didn’t cause, why don’t they?

Climate anxiety therapy

This is most widely-accepted way to treat climate anxiety at the moment. Eco-anxiety has become a recognised mental health problem, for better or for worse. With it being recognised, there are many resources people can access to alleviate their stress. They need to be promoted and widely accessible.

The global Good Grief Network have devised a ten-step programme to help people adopt “personal resilience and empowerment” in the climate crisis. It does not just validate people’s anxiety, but helps people develop better attitudes about their privileges and impact when it comes to climate change. It encourages “rest” as well as meaningful investments into climate activism.

Claudia Tormey formed the Irish Active Hope Network to organise monthly meetings for those dealing with climate alarmism. This support network allows people to build a community with others also facing eco-guilt and advocate for change together.

These networks should be widespread across schools, colleges and local communities for any young people dealing with climate anxiety. Not everyone can afford their own therapist. Joining a network of like-minded people can remind the eco-anxious that they are not alone in their concerns, and that they can seek help.

Better working conditions

Psychological help is one side, but making the climate crisis more bearable is also a material issue for young people. The current heatwave has shown that rules and regulations in the workplace need to adapt to climate change.

While people in office jobs can avail of fans in their office, or even manage to get a day off, the hospitality sector do not get that same privilege. If anything, bosses expect more of hospitality workers in a heatwave to serve large groups and families.

Of course, a lot of staff in the hospitality sector are young, part-time workers, who are exploited the most at times like this.

According to the Irish Businesses and Employers Confederation, if an employer “tries to alleviate the worst effects of hot weather, most employees should bear with temporary discomfort and continue working normally.” But what does “trying to alleviate” mean really?

Current regulations say that the workplace should be minimum 16 degrees to be workable. But is it time to introduce a maximum temperature allowed in the workplace? Normalising water breaks will also go a long way to making workers feel more comfortable working. Employers need to take a better look at the conditions their staff are currently working in.

And uniforms in the hospitality sector need to be adjusted for the heat. What do you think is worse- if a customer can see a waiter’s knee, or that your staff faints from heatstroke because you wouldn’t let them wear shorts?

Beyond the current heatwave, more conversations need to be had about how climate change is affecting people’s ability to even get to work. It’s not the fault of a part-time worker that a flood or tree on the road caused by storms prevented them from getting to work, but they are still punished through deducted pay.

We saw that the government adapted to a changed workplace through the pandemic unemployment payment. So why can’t they now adapt to helping workers through the climate crisis?

Affordable sustainable food options

A lot of climate anxiety is wrapped up in guilt that you aren’t doing enough to alleviate the problem. Sure, the climate crisis does boil down to just 100 corporations. But that doesn’t mean you don’t feel guilty for using too many plastic straws.

In particular, a lot of people feel guilty that their diets aren’t climate-friendly enough. Whether they eat too much beef, or foods out of season, a lot of people don’t have accessible alternatives. With the cost of living rising as much as the temperatures, it’s difficult to make the “ethical” choice when money is tight.

In Ireland, vegetarian options still aren’t as cheap as their meat alternative on average. But if the prices began to balance out, then young people could take what little control they have over their carbon footprint and feel like they’re making a difference.

Better outdoor amenities

It’s harder not to get stressed about rising temperatures if you can’t even enjoy the hot weather when it’s here.

Over the weekend, everyone flocked to the beaches to enjoy the unusual heat. But what happens during the week when you can’t spend a day at the beach? Or when you simply get bored of screaming kids and sand in your everywhere? What else does Dublin offer for people who want to get outside?

Benches are few and far between in Dublin beyond Stephen’s Green. Something as simple as a place to sit on a hot day is essential for your physical and mental well-being.

The city was also built for drivers rather than pedestrians or cyclists. Dublin City Council have been on the fence about making College Green traffic-free for years. A move like this would give young people somewhere to be outside comfortably and safely. If we emphasised walking and cycling in our city rather than cars which produce more hot and harmful fumes, we would have a far more comfortable time in the heat.

Dublin City Council are currently in talks to develop an outdoor in the inner city. Amenities like this go a long way to making an inevitably hotter city more comfortable.

Better public transport

This one combines the benefits of three and four. More accessible public transport can help us feel better about our carbon footprint, and better serviced transport can help us feel like we’re dying inside an overheated can.

Anyone who has been on a bus recently will know the absolute furnace they have become in the heatwave. In poorer weather conditions they’re not much better, as too much rain will delay or simply cancel your bus. Young people need more reliable transport better equipped to deal with all sorts of weather.

Outside a city, young people need public transport. Full stop. In rural Ireland, trains and buses both within a county and between counties are infrequent and skewed towards the east. How can a young person lower their carbon footprint if their only chance of independence is through driving a car? And when the price of fuel is so high, most young people can neither drive nor use public transport.

More effort needs to be put into making Ireland an accessible country across the board. Introducing bus and rail lines in more areas at higher frequencies can allow young people to gain independence and lower carbon emissions.

All of these issues are slim pickings compared to global problems caused by the climate crisis. But Ireland is already so inaccessible to its own young people. The country cannot afford to alienate us further by not addressing these issues.

Elsewhere on District: Dame Street and College Green to go “traffic-free” for one day