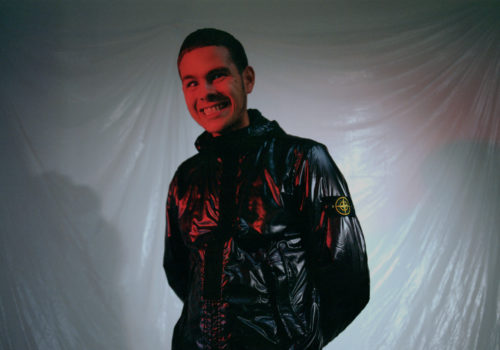

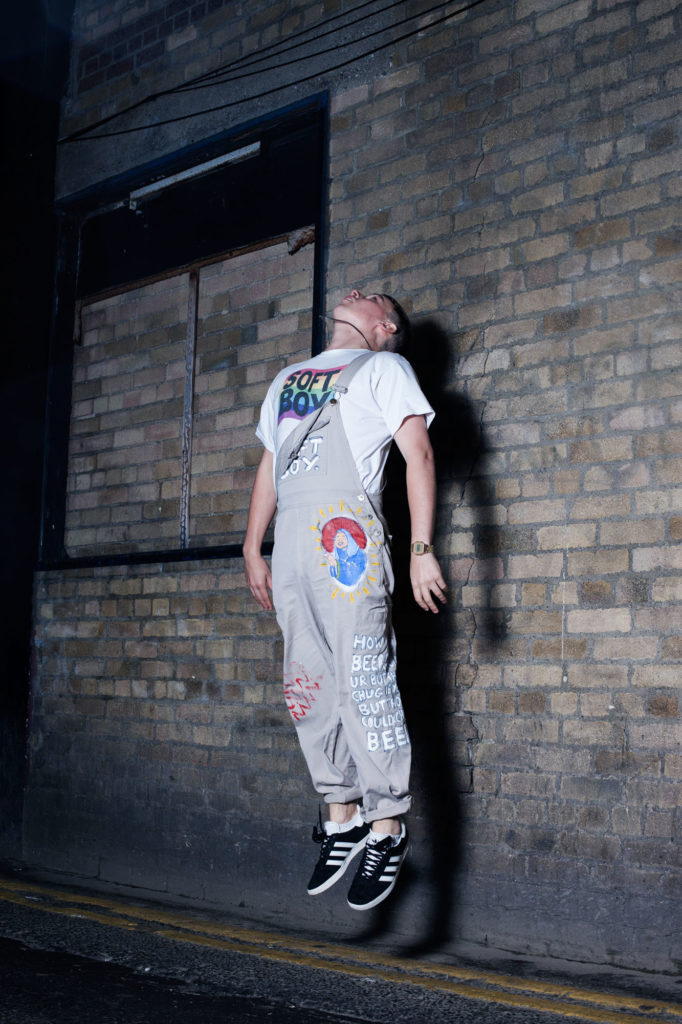

Kojaque is laughing in the face of hip hop stereotypes

Words: Eric Davidson

Photography: George Voronov

Words: Eric Davidson

Photography: George Voronov

In October 2017 we sat down with visual artist, producer and rapper Kojaque for a conversation. The interview and accompanying shoot by George Voronov first appeared in District Magazine Issue 003. Kojaque discusses toxic masculinity in Ireland and his tongue-in-cheek approach to archetypes in rap music.

Kevin Smith is a poet, a film maker, a label-boss at Soft Boy Records and, perhaps most prominently in the past couple of years, he is rapper and producer Kojaque. Or better put, Kojaque is a part of him. It’s his rap persona that combines all of the aforementioned creative pursuits into one entity that toys with hip hop stereotypes of bravado, while still making some of the best rap music Ireland has heard since the genre washed up on these shores.

We sit down with a pitcher of beer in a popular youth hostel in Dublin’s Smithfield Square. Even though I’ve had extended interactions with him, from reading other interviews where he doesn’t take things too seriously— opting to let his work speak for him — I was worried that I’d be treated with the same level of nonchalance. But it was quite the opposite.

The conversation begins with discussing how through the beginnings, the most daunting thing was being embarrassed to rap in a Dublin accent. Keeping it tongue-in-cheek was the safety net, so if it didn’t work out “it was all just a joke”. However, even back then Kojaque had a plan. He always had an acute awareness of the industry he’s in, and through his work he plays up to the often crippling archetypes that exist in hip hop; misogyny, a sense of over-compensating masculinity, and the inability to truly express emotions. Being Irish means these flaws are often exacerbated.

How long did it take you to get over that initial insecurity of being an ‘Irish rapper’?

I don’t think I was even over it when I released the first tune. ‘Midnight Flower’ was the first track I did. I was sitting on it for about a month, and for ages I was thinking maybe I won’t release it. It’s that thing, when you’re really proud of something and you don’t want to half-ass release it.

I think you end up painting yourself into a corner where you’re proud of it and want to release it but afraid it won’t do well… You’re worried about what other people think, which isn’t a good mindset to be in when you’re trying to create art. Was there an initial message you wanted to convey when you started making hip hop? I don’t think I even wrote any tunes when I was trying to get my friends into hip hop. I was very naïve about it and just assumed it was easy. You’d see people like Odd Future and it was almost like a movement. It was the same way you’d hear people talking about punk. We were alive when Odd Future happened, so we attached to it. They were people around my age who seemed to be doing it willy-nilly and were doing really well from it. That’s what I assumed it was like. You just make one song, put it up and that’s it. I remember I put up ‘Midnight Flower’ and it was up for like a week before it started doing well. Overnight it had like 100,000 views and I thought ‘this is it, I’ve done it, I’m going to be a millionaire and signed and people are going to ask me for gigs all the time’. That’s not the case. I’m very proud of it and it did go viral in a sense because no one had done anything like that before. It’s like a double-edged sword. I got a lot of traction from it and a lot of people were watching, but at the same time not a lot of people were there for the music. But it was a good start.

“That’s the thing with a lot of hip hop, it’s this veneer from the outside looking in, of this unstoppable person or hero that’s almost emotionless. Makes money, hates women and doesn’t think about emotions.”

Kojaque

Are there any parallels the short film you recently directed and starred in ‘Love in Technicolour’ and the concept of your musical work?

Yeah. ‘Midnight Flower’ kind of fits into a body of work that’s conceptual, like the film. I was writing a lot of poetry around the same time and a lot of it was about grappling with masculinity in a sense, and when relationships go awry.

A common theme for a lot of young men is this inability to express themselves properly and that manifests itself in frustration and aggressiveness towards other people. I worked on a film then for a whole year which was based off the poetry and narrative that emerged from that body of work. A lot of people have still yet to hear it.

You mentioned the idea of fragile masculinity – that’s prevalent in the film and in your music as well. Especially hip hop, often it’s this macho mask, disguising fragility and softness. Is that a dichotomy in your work that you like to explore?

Bravado but at the same time insecurity. That’s the thing with a lot of hip hop, it’s this veneer from the outside looking in, of this unstoppable person or hero that’s almost emotionless. Makes money, hates women and doesn’t think about emotions. That’s something that comes up in my work a lot, Kojaque is a character almost. It’s a paradox that walks the same line between braggadocio, but also emotional.

It seems you’ve always had awareness of that. Do you think that problem isn’t just prevalent in hip hop, but in Irish men or masculinity as a whole? That inability to express emotions?

I think we do have a culture of repression, as far back as we can think. It’s natural that it’s going to be ingrained. I went to an all-boys school. There was an all-girls school on the same campus, but they kept us separated. In traditional Irish society the instances where boys meet girls is at religious events or when we are drunk, two instances when you’re not your natural self. You don’t get to grow up at the same time as women, at least I didn’t. It’s mad, the way everything was set up was trying to pit the two genders against each other. Girls are taught to act a certain way in girls’ schools and boys are taught to act a certain way in theirs. And you only ever see them if you’re going to church or get pissed. That’s an associated feeling — if you want to talk to girls about how you feel you get langered and then you text them, or you meet them in a night club. It’s not healthy.

“In traditional Irish society, the instances where boys meet girls is at religious events or when we are drunk, two instances when you’re not your natural self.”

Kojaque

What’s the fallout from that?

Unfortunately, women are taught their place and men are taught not to express themselves. It gets ingrained in us. Then I did art in a third level course and I was one of three lads in the class. It was a flip of a coin, it was like a culture shock because I went to Christian schools.

In ‘Love in Technicolour’ I picked up a crippling sense of loneliness — surrounded by people but totally alone. What was the concept behind the new short film?

It’s half way between a performance art piece and a film. I did a lot of the research in both. People like Chris Burden, an artist who was shot through the arm with a rifle for a performance piece. Marina Abramović, Amanda Coogan. One thing that struck me was that the camera was always purely used as documentation in any performance art piece. A stationery camera that recorded what the performer was doing in front of it.

I wanted to be more inclusive, have the camera as a performer in itself and walk that line between cinema. A lot of cinema I watched – like David Lynch’s ‘Eraserhead’, that abstract surrealist work – was half way between a performance art piece and a film.

I think that classic role of the tortured artist is a ridiculous thing to try for. You don’t want to be on the brink of destroying yourself for the sake of making art for the people.

Did you find it hard to tread that line between film and a performance piece, keeping it authentic?

I’m not sure. I started out with a list of performances I wanted to do then reverse engineered it into a narrative so that you were able to follow the piece. I think a lot of art suffers when it gets stuck within the art realm. It can be very jarring to those that aren’t within it. It’s almost elitist. I wanted to make something that was quite familiar to people who would randomly walk in off the street. Something uniform, well lit, well shot. I wanted to drag people in.

Do you think that your concept will be diminished now that you’re in a healthy relationship?

Not at all. I think that classic role of the tortured artist is a ridiculous thing to try for. You don’t want to be on the brink of destroying yourself for the sake of making art for the people. It’s crazy, not a healthy business. Healthy relationships are great, they really help you grow, understand who you are, understand compromise. You can’t just think about yourself forever, it’s very important to think about other people. It’s allowed me to explore themes outside of my personal life. I don’t ever want to tread too closely between who I am as a person and who Kojaque is because I think that makes it into celebrity, almost. It makes your art only as interesting as gossip.

There are a lot of times when I think I’d prefer if I was walking around with a plastic bag on my head when I was doing this stuff. It would mean people wouldn’t have to know about my personal life in order to understand my art. That’s another issue about art; people always want to know the answers to it, or what the artist meant. I think that can ruin it in a sense. I’d be happier to press play on the EP and tell them that the answers are there, they can pick their own meaning out of it.

Speaking about the EP, can you tell me much about it yet?

Well, the title is a work in progress, but the EP is a conceptual project about someone working a nine to five in a deli. It pretty much explores that feeling of subdued anguish that comes when you ignore your passion just to make a bit of cash. Some of the songs do feel more personal and some feel more like accurate reflections of the situation we’re in as young people trying to live and work in this city. You’re between a rock and a hard place, either you put yourself in debt to get educated just so one day you may land a job to make enough money for rent, or you work the nine to five to scrape by which often means your passion gets put on the back-burner. I think it’s easy to fall into that feeling of hopelessness, but there’s light at the end of the tunnel, there’s light in the people making art in this city. That’s where the hope lies for me.