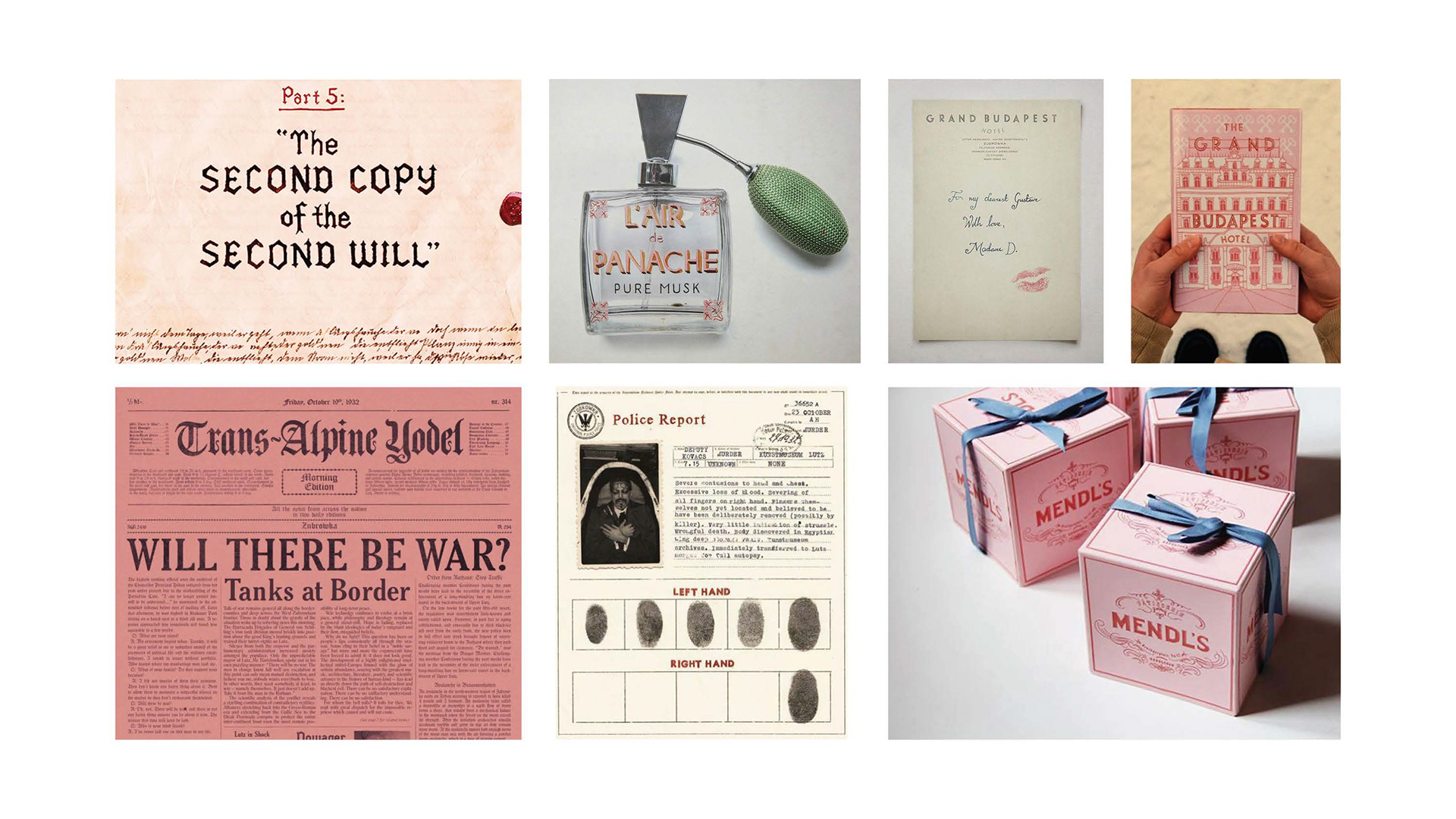

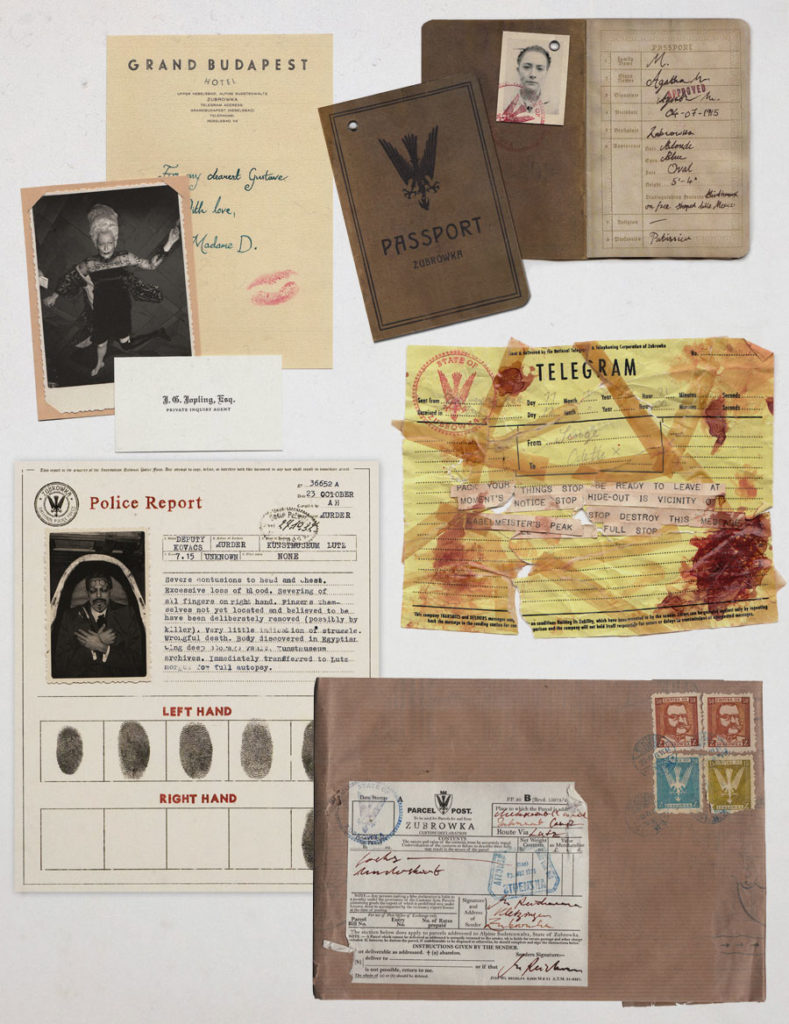

Artist Spotlight: Annie Atkins is the designer behind The French Dispatch and The Grand Budapest Hotel

Words: George Voronov

Photography: Annie Atkins & Guinness

Annie Atkins has what might be referred to as a dream job. As a graphic designer for the film industry, she creates graphic props and set pieces for movie productions all over the world. Having worked across multiple visually stunning films including Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel, The French Dispatch and Steven Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies, her work has accrued legions of fans from all over the world. Annie exudes a joy for design that is infectious and energising. We caught up with the acclaimed designer ahead of the opening of Winterfest 2021, an immersive experience that she is curating in the Guinness Storehouse.

You have one of those really interesting jobs in that a lot of people might not even be aware that a job like that exists. Was there a particular movie that made you think that design for film is what you wanted to do?

It’s funny isn’t it? I didn’t know that it was a job either. There was no movie that I saw that made me want to design graphics for film because I never saw graphics in films. I’ve been working in graphic design for so long and I’ve watched movies my whole life and even still I never put two and two together.

It wasn’t until I went to film school after leaving a job in advertising design that I understood that this was a possible career path and it wasn’t until I actually got my first job that I began to be able to recognise graphic design in film. I think up until that point I must have thought that it was all incidental. I thought that if you saw a character reading a newspaper in a movie they must have just used a newspaper that they found or… something? I don’t know what I thought but I certainly didn’t think it was a job.

You mentioned your pivot from working for an ad agency to working in film. I think a lot of us can fall into the trap of assuming that career paths are very linear and that they don’t have any radical changes in direction. Can you tell me a bit more about when you decided to stop working as a designer for agencies and move into this new world of film?

I do think that people often assume that careers are very linear. I did as well. I graduated with a degree in Visual Communication and then I went to an ad agency, McCann-Erickson in Reykjavik.

In Iceland, people don’t tend to have one career, they do a lot of different things. Everyone I worked with in the agency was also a novelist or a musician or something. That’s when I first started to think that I didn’t necessarily have to be a graphic designer forever.

Also, I was working in advertising but I wasn’t really enjoying it. I always felt like I wasn’t very good at graphic design, or at least, at graphic design for advertising. When I decided to change my career and go to film school I thought I was going to do something completely different, I thought I was going to go learn how to operate a camera or write a screenplay or direct maybe.

Was that a scary time?

Oh no, it wasn’t scary at all. I was only 27 when this all happened. It was like a big adventure. I didn’t have a care in the world. I didn’t have any responsibilities, no mortgage, or children or anything. I felt like I could do anything.

But then, when I got to film school, I very quickly realised that all the things I thought film-making was, I really didn’t want to do. I had no interest in camera operation. I didn’t want to learn how to light a set and I definitely didn’t want to be a director.

I remember on our first day, the tutor said ‘everyone here who wants to direct, put your hands up’, and everyone in the whole class put their hand up. He said, ‘I guarantee you that by the end of this year, over half of those hands will be down’. And I remember thinking ‘No way! Of course I want to direct. Everyone wants to direct. That’s the main job, right?’. And sure enough, I had this whole other world of filmmaking open up to me which was design for film. It never occurred to me that I could be making the things that the actors and the directors had to use. I took to that like a fish to water.

I noticed that a blurb for one of your books described your job as ‘meticulous’ and I thought that was a really interesting word to use. I wanted to get your sense on that. Did that meticulous quality come naturally to you? Were you always able to sit down with paper and glue and just carefully make something or was that something you really had to develop over time?

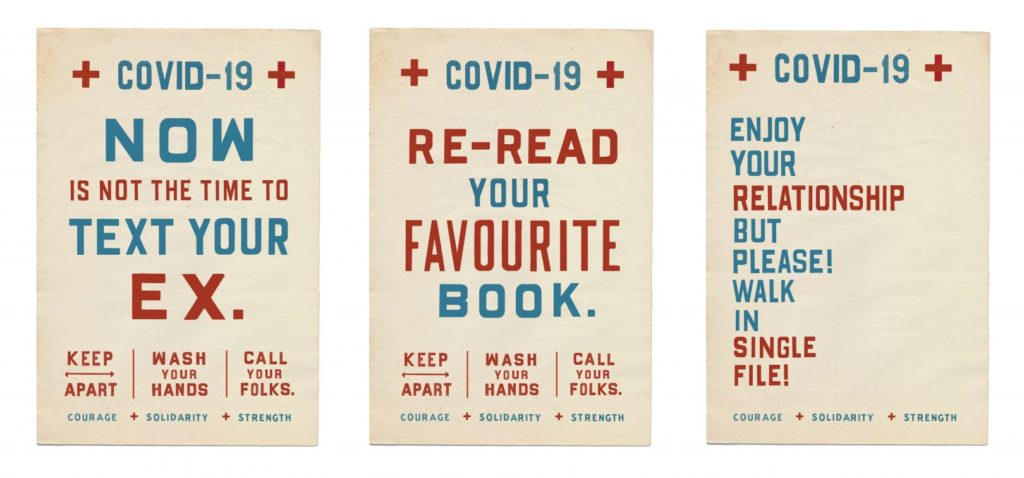

My mum was an illustrator and my dad was a graphic designer but they were both very into using analog tools. I was much more into using paint and bright colours. I came from this more tactile, messy background but for work, in advertising, I had to work digitally. This was about twenty years ago before hand-lettering became fashionable. In the last few years, hand-lettering and painted lettering has become very in vogue.

Yeah it’s gotten quite trendy.

Absolutely. Very trendy. But it wasn’t back then. And it wasn’t when I started working on The Tudors. On The Tudors I was able to work as if it was the 15th century. I was literally using feather quills, dipping pens and ink, all these funny tools and materials. I felt much more at home then. You do have to be organised but you also have to be crafty. You have to be ready to use your hands and get dirt on your clothes, you know? I’ve never been great with things like digital type setting but I’m pretty nifty with a pencil.

I’ve never been great with things like digital type setting but I’m pretty nifty with a pencil.

Annie Atkins

So much of your work–and especially the stuff you made with Wes Anderson– is from the early to mid 20th century. To me, your sensibility harkens back to a kind of golden age – a time before computers and mass consumerism. I was wondering if you personally have a preference for a more period-type aesthetic or do you also have time for futurism?

It’s funny. I don’t think it’s so much about antiquity for me. I think I really value seeing handiwork in things. I really love shopfront sign painting but it doesn’t have to have been painted by the best sign painter in town. I really love the sign painting that maybe has a little bit of dodgy kerning in it.

Does that sensibility transcend to other parts of your life? Do you value that approach in the clothes that you wear for example? Do you think you’re more of an analog person in general?

I don’t think so, you know? I don’t have a record player for example. I listen to music on my phone and I have a lot of flat-pack from IKEA. However, I also have a lovely old farmhouse kitchen table. I definitely think that this design aesthetic has come directly from working in the movies. I think that if I had never started working for film, I would have never had my eyes opened up to the type of craftsmanship that I now imitate.

If I had never started working for film, I would have never had my eyes opened up to the type of craftsmanship that I now imitate.

Annie Atkins

I was going to say, maybe it’s a false dichotomy. Maybe you don’t have to be one or the other?

Yeah, maybe. I don’t work in contemporary settings very often and I never do sci-fi. I’ve only done like two futuristic things – Isle of Dogs was set twenty years in the future but it was never specified in the script from when. A lot of that look was inspired by a Japanese 1960s aesthetic. That was a kind of funny fictitious period. Then I did another sci-fi years and years ago about a spaceship which got axed and another production company ended up finishing it. You know what, it’s just not for me. That’s for another film graphic designer to do. I generally don’t take that work on anymore. I got offered the new Matrix movie last year and I just had to turn it down.

That’s gas. I was literally just about to make the joke that I guess we won’t be seeing your work in the new Matrix movie then.

*Laughs* Yeah. I was kind of thinking afterwards maybe I should have done it. You know? It’s fun. On one hand, maybe I should take myself out of my comfort zone and try something new. But then on the other hand, I’m 41, I have a family now, I’m quite happy doing Victorian shopfront signage again and again.

I always say that when I left advertising I was doing the same thing over and over again. I wanted to do something different, I wanted to be challenged. And then I went to filmmaking and now I’m challenged all the time. It’s a race against time. There’s so much to produce for a movie. And I’m finding now that maybe I don’t want to be challenged all the time. You know?

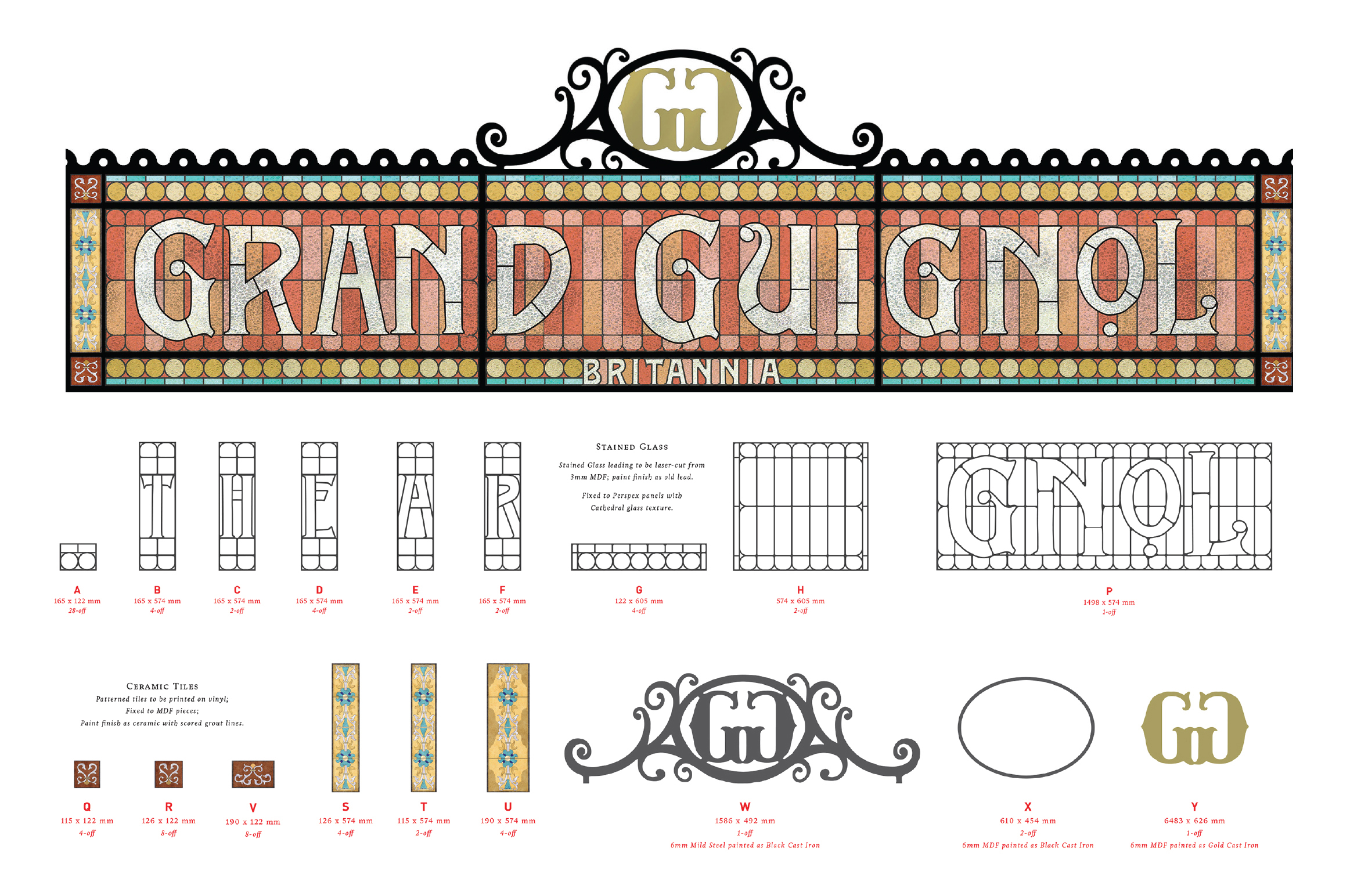

I think it can be pretty empowering as a creative person to get that feeling of “you know what, I got this”. In terms of challenging yourself, you’re curating an exhibition for Guinness at the moment, what was that process like? Have you curated any exhibitions before?

You know, when they contacted me I realised that I had always really wanted to do that job. I’ve always loved the Guinness branding and design. They’ve always done such beautiful and well executed things. I immediately wanted to do it because it was Christmas and I just love festive work.

It’s such a beautiful time of year to design for. Festive lettering, festive patterns, it just feels so lovely. I wanted to do it immediately and it felt like it was something I could really get my teeth into. You know, a lot of stuff we make for film is never actually seen. It’s in the blurry background or it gets cut or whatever. Whereas something like this Guinness exhibition, people are actually going to be able to go and experience it.

You that you design things for the actors sometimes even more-so than for the audience. I was wondering if there was ever a time that an actor gave you notes on how to change one of your objects because of their reading of a character?

It does happen, not often but occasionally. When an actor comes in for a costume fitting, they try on all their clothes and we make sure that everything feels right for them. It’s not just about how it fits but how it feels. The same goes for props.

We made a notebook for Ralph Fiennes’ character in The Grand Budapest Hotel. He was playing Gustav, this really particular concierge who was a perfectionist – everything had to be done a certain way. We made his notebook which is where he made all his little notes as he walked around the hotel. I remember when Ralph Fiennes came in for his fitting, he picked up that notebook and I remember he said that he felt that it was out of character because the notebook didn’t have lined pages. We had given him this nice shorthand writing style but it was on blank, unlined pages and he didn’t think that his character would ever write in a notebook that was unlined. The prop-master radioed up to the art-department, we put lines into the notebook, and sent it back down and then it was approved.

I remember using that as an anecdote to explain just how much detail we go into to make all of these piece. You know, a camera is never going to see that. The cinema audience is never going to see whether there are lines in the notebook or not. It’s never going to get a close up. But, it’s important to the cast. And it’s not that the cast are being fussy. It’s just that it’s part of their job to make sure that these things are right for their character. There’s nothing better that hearing from the set that the cast walked in first thing in the morning and they were completely transported into Victorian London or Zubrovka or mid-century New York or whatever.

Ok last one, what is the one piece of advice that you would have given to yourself at the start of your film career?

Well something I always tell to my students is that if somebody asks you a question and you don’t know what the answer is don’t panic, don’t make something up, all you have to say is ‘I don’t know, let me check that and I’ll get back to you’.

‘I’ll get back to you’ is such a valuable phrase

Absolutely! It takes so much confidence to day ‘I don’t know’ and it’s only in recent years that I’ve been able to say “I dunno. But. I’ll find out”.