JOYRIDER documents growing up in Ireland’s most notorious housing project

Words: George Voronov

Photography: Ross McDonnell

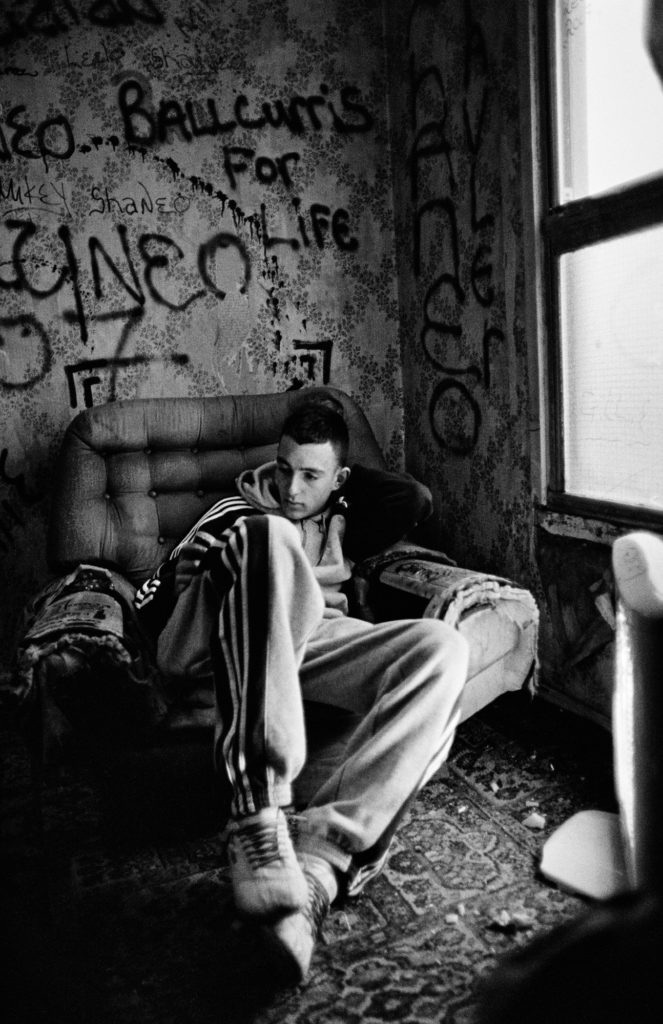

Late last month, Irish photographer Ross McDonnell launched his debut photobook Joyrider in The Gallery of Photography. Adorned with a jet black cover, reminiscent of the dashboards of Honda Civics, the book is the culmination of Ross’ tireless dedication to telling authentic stories rooted in the Ballymun housing projects. Fundamentally, the book is presented as a coming of age narrative loosely following the group of young men that Ross met on a Halloween night in the early 2000s. The book documents rites of passage on the ‘block’, “experiences that convert youthful abandon to criminal enterprise.”

Once opened, the book strikes you with a ferocity that needs to be experienced to be believed. The images are searing hot, in no small part due to their almost uncomfortable closeness to increasingly frenzied action. Ross is a cinematographer by trade, a fact which seems retrospectively obvious as soon as you dig into the propulsive cinematic energy of his images. We caught up with the now New York based photographer to dig deeper into his work.

Can you describe the events that led to you finding yourself in Ballymun and getting involved with the group featured in the book?

It was during the Celtic Tiger and I was trying to photograph in Ireland seriously for the first time. I was also really engaging with my Irish identity in many ways during this time. I had been away for a couple of years and when I came back there was a huge feeling that the country was being reshaped into a more homogenised, corporate version of itself.

I struck out with my camera with this notion to capture some sense of the wild, untamed side of Ireland. I think the folder on my computer was called ‘Days of being wild’ or something like that.

That led me on Halloween in 2005 to hop on the 17A to Ballymun with my cameras to see what was going on. I knew that it was a place where there would be bonfires and stuff happening. It was then that I met the group of guys that eventually became the focus of my work.

So to zoom out for a minute before we go deeper into the project itself. Can you ground us in the socio-political context of Ballymun. How did those housing projects come about?

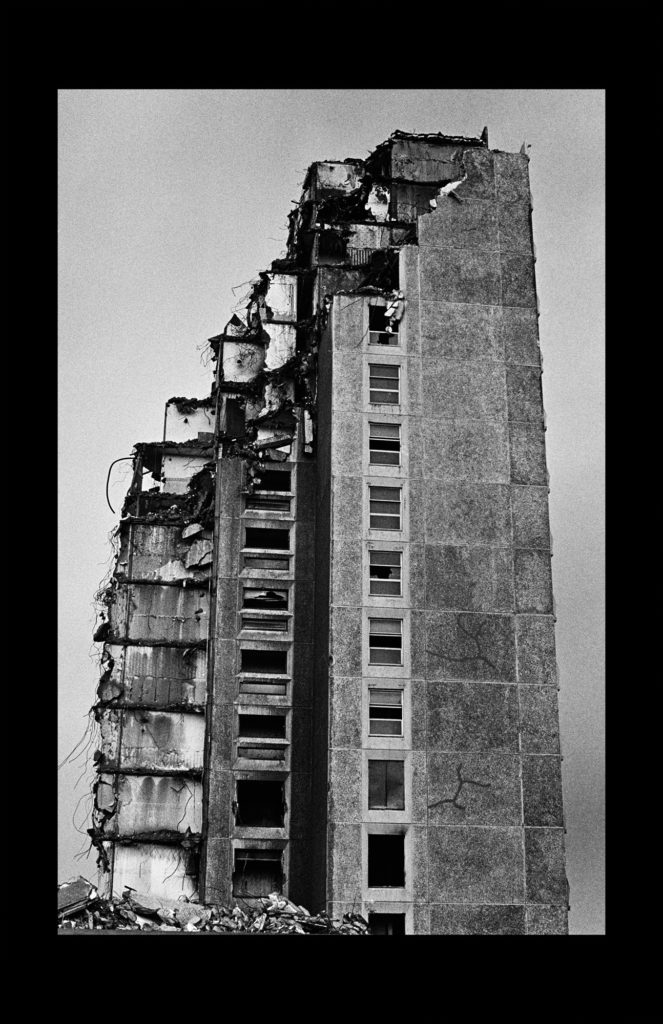

I think it’s a very similar situation to what we have now. The government were trying to address a need for housing and also to move their problems somewhere else. It’s like ok, the inner city tenements are an issue, and at the same time they are prime real estate for developers. We need to address this and create a space for people. You start to see very quickly in Ballymun that things unravelled because they weren’t provided amenities, they weren’t provided bus routes, they weren’t provided shopping or leisure facilities.

You start to see very quickly in Ballymun that things unravelled because they weren’t provided amenities, they weren’t provided bus routes, they weren’t provided shopping or leisure facilities.

Ross McDonnell

I think it’s important to say that Joyrider, while being set in Ballymun is not necessarily about the community of Ballymun or meant to represent the whole arc of the Ballymun housing projects. The photographs have resonated over the years because this is happening in a moment in time in young people’s lives all over the world. It’s a phenomenon we see replicated in all different places from Russian to Brazil…

It could have been shot anywhere.

Yeah it could have been Chicago, it could have been Brazil, it could have been Moscow…

Anywhere urban basically.

Yeah I think there are always urban centres at some point in time that experience this sort of transition. Whether that means we have to question the forces that create it or whether you can read into the narrative of it is the interest of the book but like I said it’s not a book that should exclusive speak to the community of Ballymun it’s more about self contained stories within that world which can resonate beyond it.

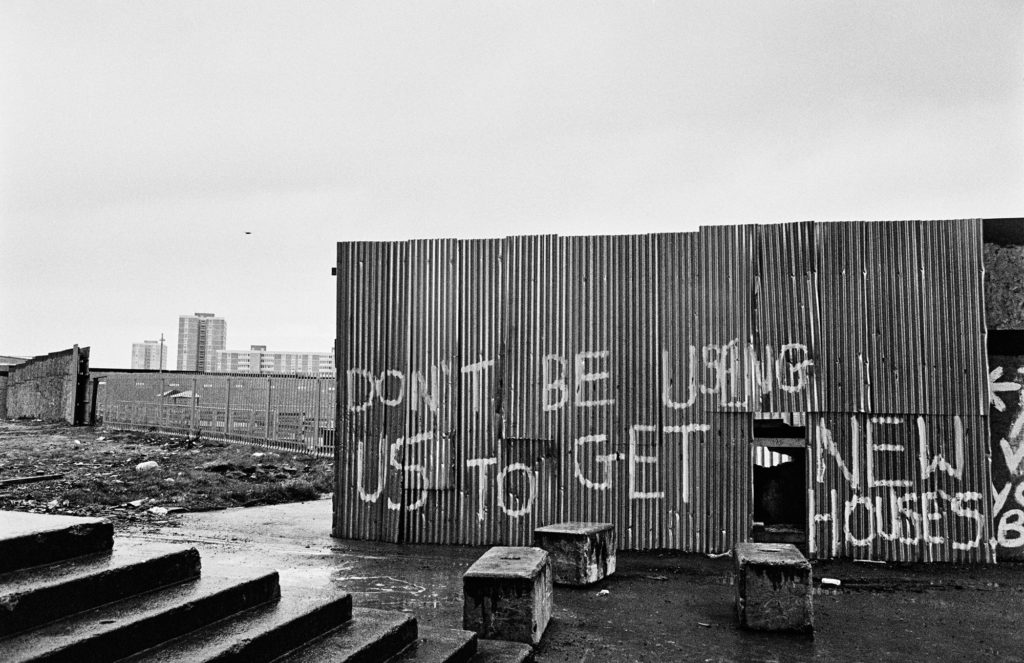

You mentioned a similarity in circumstance between when this work was shot and when it’s being published. The housing projects that you photographed were a response to a housing crisis and we are now in the middle of a housing crisis ourselves. I assume that it was a conscious decision to make that link.

Yeah, absolutely. When I was editing it started to come through very strongly. I had these images that had been published which were originally more about transgressive youth culture but now really resonated in terms of this sense of freedom that these young guys felt in reclaiming this space that was a gigantic failure of social housing and planning in Ireland.

There’s that one picture in the book that’s like “Don’t be using us to get new houses”. That sort of sentiment is now write large across the country. It has sort of transcended this social housing discourse into a national housing discourse. As we edited the book it became much more about the relationship to the space and to the buildings and this sort of relationship between creation and destruction. It was sort of like, without getting too deep into it, that there is a kind of psycho-geography.

I think you’re spot on because that idea of reclaiming the space is also what happens when frustration boils over. In this instance, being surrounded by an infrastructure that doesn’t function creates a society that doesn’t function. It seems that now we’re all living in a country where there is a similar sense of frustration on the boil.

The narrative around Ballymun was that it was built around that idea of Le Corbusier- this utopian society. And in a way, when you flash forward to now, the government is still saying that we’re creating a utopian society. But we can see that it’s not working.

When you watch all the old newsreels from Ballymun when they have these new buildings and they’re moving people out from the inner city tenements, there’s documentary footage of people leaving on a horse and cart with three plastic bags for all of their belongings. And there was a sense that they were on their way to a utopian future. We’re still being told that this utopian ideal of ‘everyone’s going to get sorted’ is happening whereas the reality is that we can see around us that it’s not the case.

We’re still being told that this utopian ideal of ‘everyone’s going to get sorted’ is happening whereas the reality is that we can see around us that it’s not the case.

Ross McDonnell

You’re a filmmaker as well as a photographer so I’m interested to know what’s the relationship between film-world and photo-world and how does it inform your photographic practice?

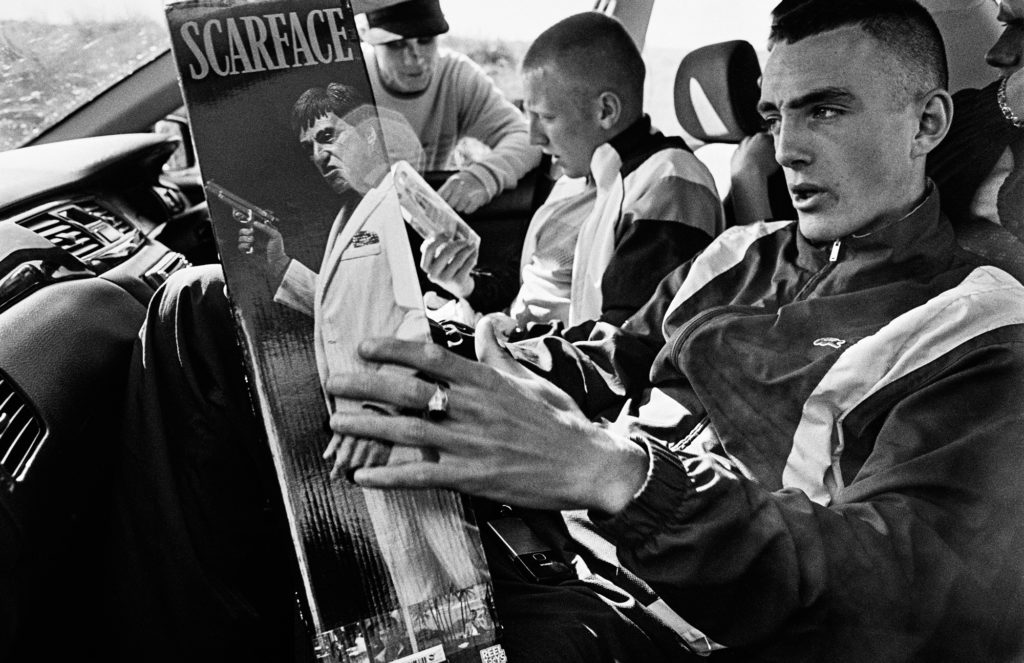

I think they were always separate parts of the same thing. I very much wanted to be a film director growing up. I was obsessed by movies. I was just super into the cinema; staying up late, recording films on VHS tapes, you know, devouring that sort of early teenage cinema – Scorsese and Coppola and all the usual people. You don’t understand anything about the film business at that point just that there’s a director and that’s cool.

All these incredible directors were working, making incredible work for David Bowie and the Beastie Boys and all of this really high level production value stuff. That’s really what inspired me. I wasn’t really inspired by documentary photography or photojournalism. Once I was comfortable bringing the camera up to my eye, I was very much channeling all of these movies that I had seen.

What I found interesting is that most of the photographs are of men. It was interesting to think what the relationship is between this project and the specific theme of masculinity?

After I started publishing this project I became very aware that the more feminine-influenced photographs in this project didn’t quite fit into the same narrative about this coming of age moment of being a young man. There’s lots of different pictures of the group that I know in Ballymun in that book but in essence it could be one character. It could be this one young man in this transitional moment. It’s a sort of classic coming of age story which is what I wanted it to be.

I did feel a huge amount of guilt that I hadn’t represented the female voice in this project. I went back and spent another year making a documentary film about young women who are part of a women’s storytelling group called Remember Me My Ghost. The film is one woman’s story of her life and her struggles with domestic abuse, drug addiction, very similar themes to those that are represented in this book.

To be clear, for me it’s not just about female representation for it’s own sake. What’s interesting for me is that this dark side of masculine energy is being used here as a vehicle to talk about a larger energy in an area.

I wanted to very clearly dig into that. I’m not mixing my words here but at the same time it’s not a blunt object either. It is supposed to be nuanced and also represent my own journey. This project is also me coming of age as a photographer in that space. There’s obviously a real comfort within that group and mutual acceptance. Trying to represent that masculinity was really interesting.

For all men, we’re all going through that. We’re trying to embrace or reject our identities, or find our vulnerabilities, or plough on regardless.

Ross McDonnell

You know, a lot of my subsequent projects were also these coming of age moments where I had been drawn into these places that were undergoing transitions. Working in Ukraine during the revolution, you started seeing a lot of these young people signing up to be soldiers and they’re sort of defining their male identity in these moments of flux.

For all men, we’re all going through that. We’re trying to embrace or reject our identities, or find our vulnerabilities, or plough on regardless. All of those things are represented in this book in a way. I think in the time that these pictures were made it’s interesting to see the bonds that were formed without the emotional openness that young people address today.

For me, it’s about the raw emotion. I think a lot of it is anger and unchecked frustration and resentment and how that can explode in these outbursts.

Yeah. Photography is powerful for me when it’s allegorical. I want images to be visually dynamic that you can look at and be like ‘Wow, I’m not even thinking about what this might mean. This is just a great photo’. I’m really into that. And then, when you have a successful sequence or image you can also say ‘this is making me feel a certain way about this’. I think you have to build your projects to have this allegorical thing whereby you are into it on a visual or surface level and then anyone can put forward an idea of what they’re taking away from it.

What was the reaction among the community to the book’s publication?

It’s important to reiterate that Joyrider is a book set in Ballymun but I’m hesitant to say it’s a portrait of the community or that it’s about Ballymun. Joyrider is a very specific vision, the editing of the images are sequenced and paced in a certain way to communicate this sense of energy, this joyride that the viewer is taken on leafing through the book.

I worked in Ballymun for many years after this particular project finished up, again on vignettes, series of photographs and films that communicated something to me. I certainly don’t want to say the work I did there represents the community in Ballymun and feel a sense that now is the time for reciprocity. Is there a project to make with and for Ballymun today?

That’s where I’m at in 2021.