How did hiking become cool? Fjällräven on gorpcore and sustainability in fashion

Words: George Voronov

When it comes to fashion in the post-Covid landscape, we’ve noticed a few key trends emerging. First, a continuous series of lockdowns have us spending more and more time in the outdoors as we bundle up in newly bought down jackets and wag our chins in frigid parks. This new demand for performance outerwear dovetails neatly with the pre-existing proliferation of ‘gorp-core’ and the fetishisation of outdoor clothing in the fashion world. Lastly; a very slow but steady creep towards the prioritisation of sustainability in fashion.

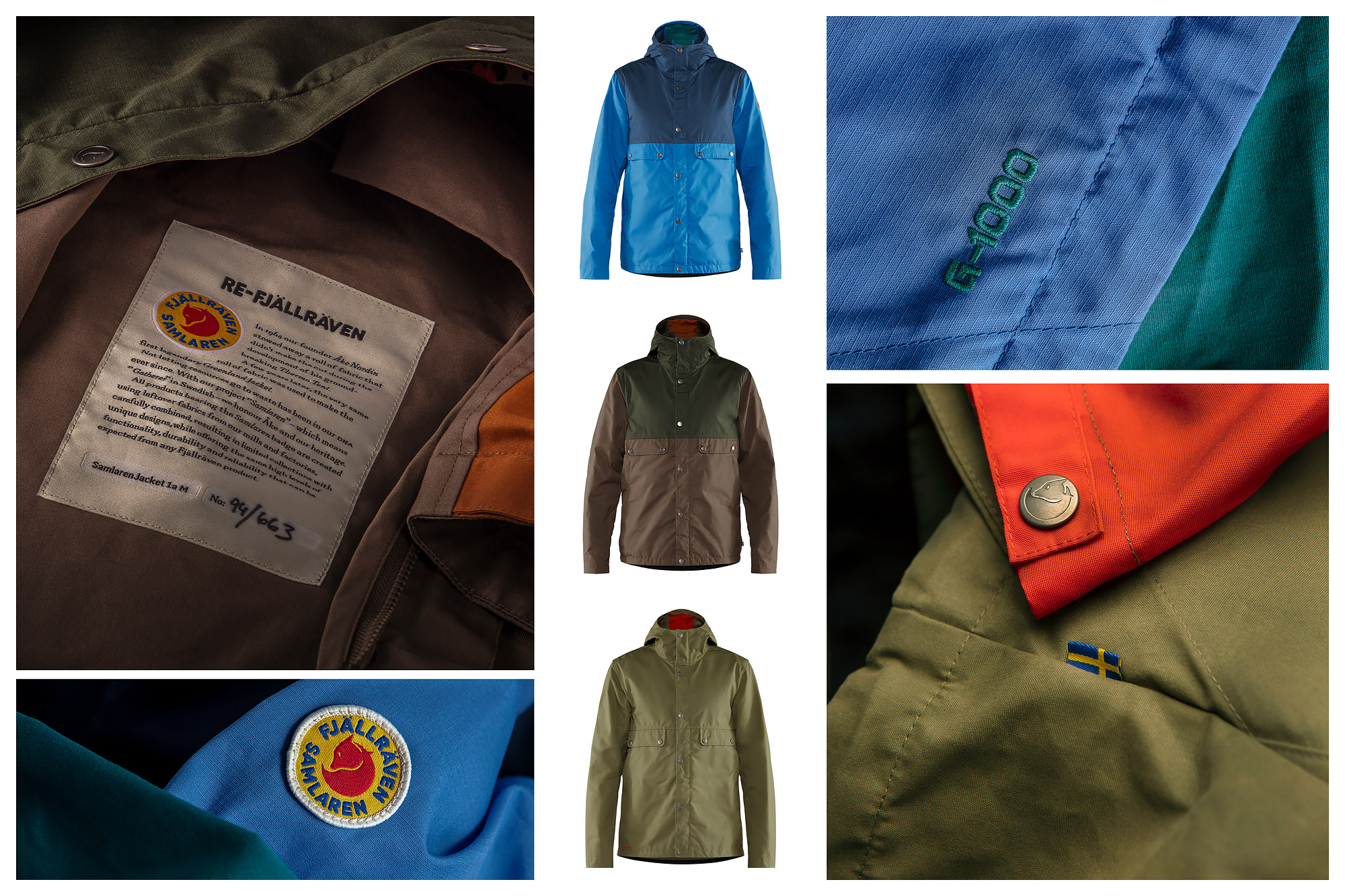

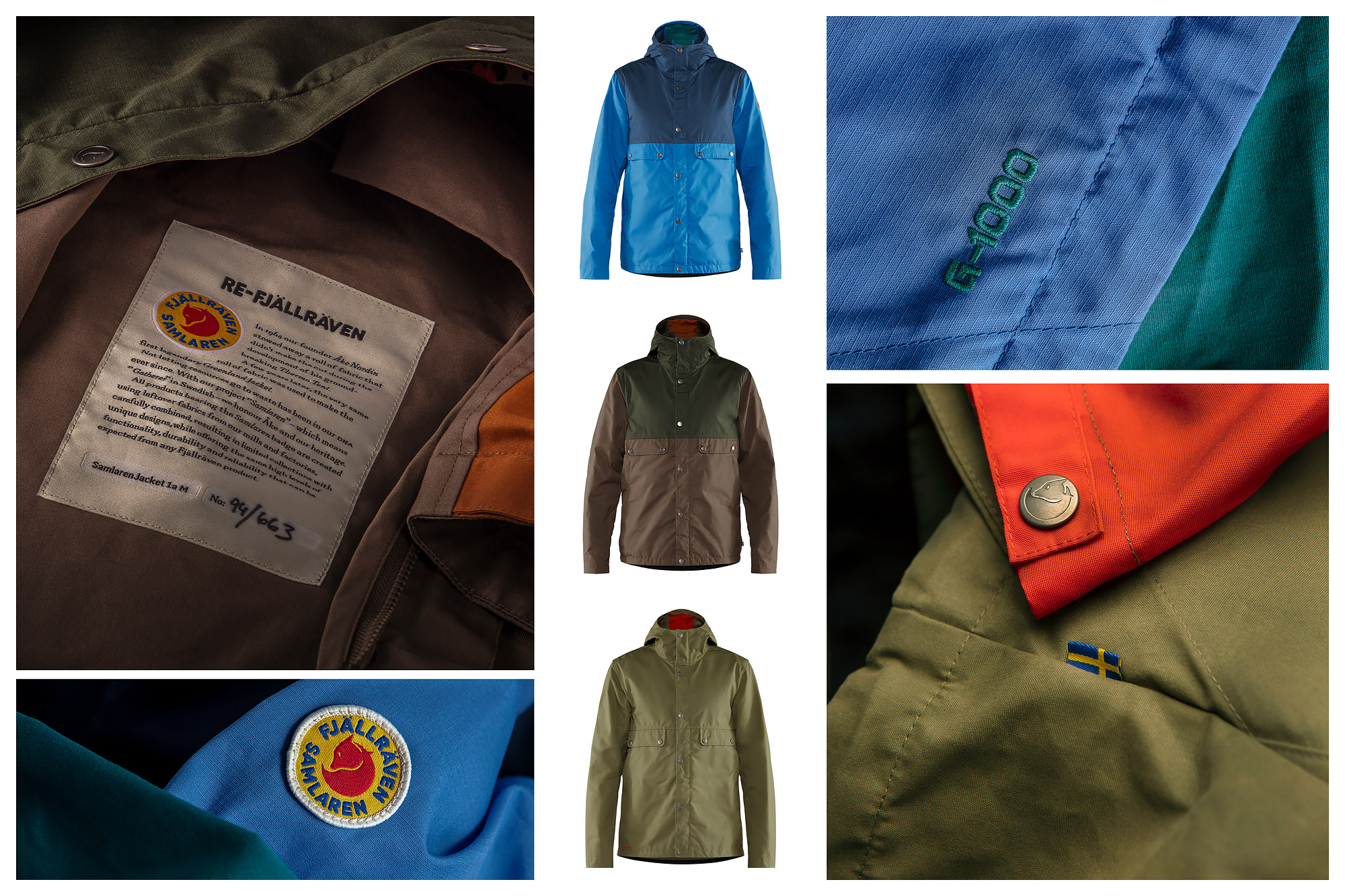

Naturally, the outdoor clothing companies that are seeing an uptick in demand for their products are also market-leaders for sustainability practices. In light of this, we spoke with Christiane Dolva Törnberg, Head of Sustainability at Fjällräven ahead of the launch of their Samlaren range – a product line made entirely out of deadstock materials – to discuss sustainability in fashion, how hiking became cool, and how more people can begin to enjoy spending time in nature.

District: In Ireland, you guys are known primarily for that iconic schoolbag but really you have a proud heritage of making outdoor gear. I was wondering if you could tell me a bit more about that because I think it’s important that people understand that there is a lot more to Fjällräven than just the backpacks.

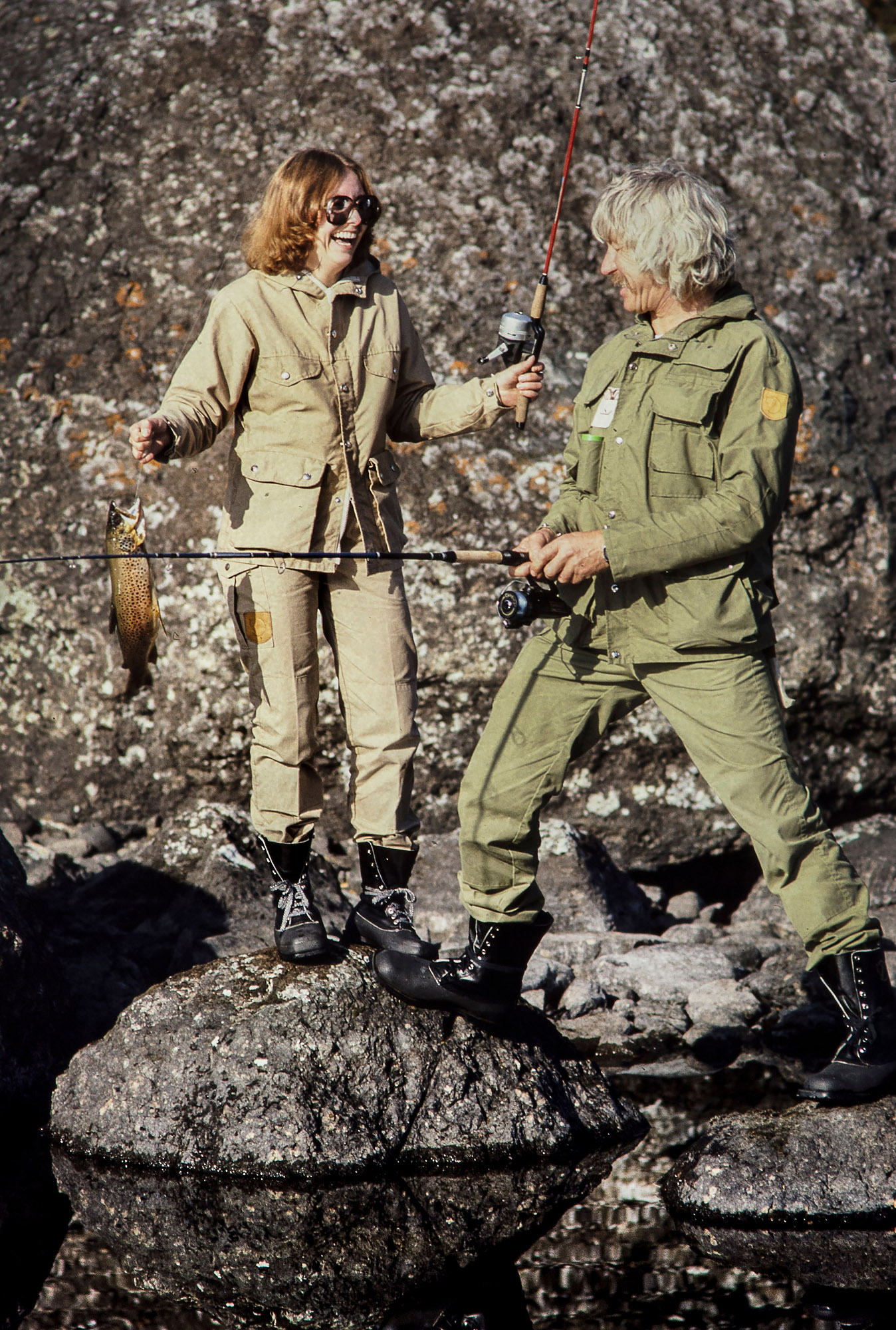

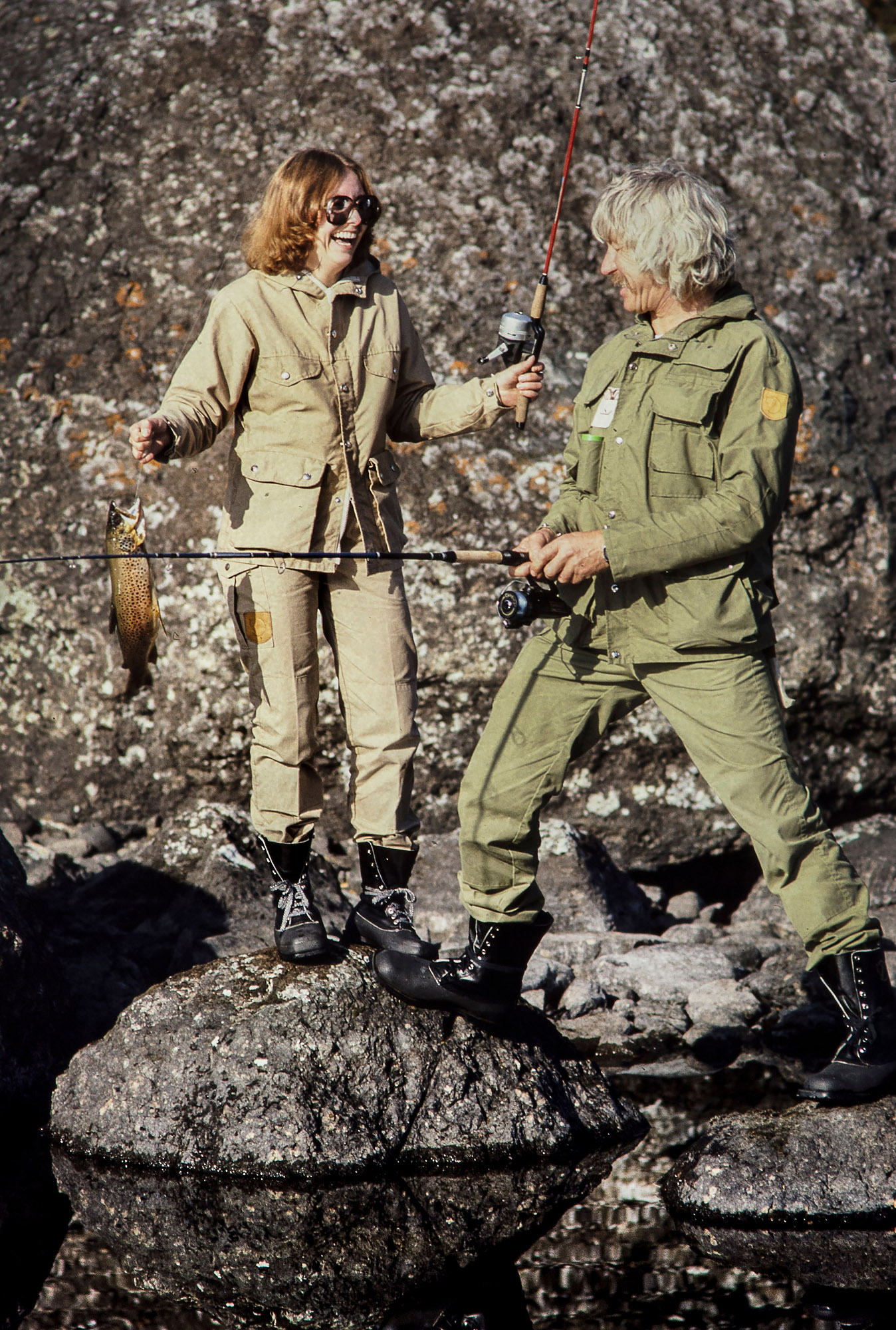

Christiane: Yeah and thanks for asking because we started off with a lot more than just that backpack. Our founder Åke Nordin was living in the North of Sweden and really loved spending time in the outdoors. The first products that were developed were basically him just figuring out and solving problems to be more comfortable out in nature.

He was inspired by an expedition that went to Greenland so he made a point of working in a lot of feedback from other people who essentially made their living in the outdoors and designed a lot of those products based on that. That’s where we come from and that’s really the core of everything we do now. We develop products with activities in mind mainly because we want to solve problems and inspire people to spend time in nature as comfortably, as warm, as dry, and as functionally as possible.

From a sustainability point of view, the Samlaren collection is super interesting because it’s made using only deadstock materials. I’ve noticed a few brands using deadstock materials more and more. Is it exciting to see other brands follow Fjällräven’s lead when it comes to reusing materials?

I think it’s exciting to see any sustainability-related philosophies spreading. A lot of the different topics that we work with are so much bigger than what one brand can solve. If you look at things such as better production processes, more efficiencies in the supply chain, and so on, the more of our colleagues in this industry that are on board with that, the easier it will be because we will all be pushing for the same results. That’s super exciting.

The first Fjällräven jacket was created because our founder had some leftover fabric that wasn’t suitable for tents but turned out to be really suitable for jackets. He had that mindset of ‘how can I use whatever is lying around my garage’. We’re trying to bring that sort of mindset back into clothing.

The first Fjällräven jacket was created because our founder had some leftover fabric that wasn’t suitable for tents but turned out to be really suitable for jackets. He had that mindset of ‘how can I use whatever is lying around my garage’. We’re trying to bring that sort of mindset back into clothing.

Christiane Dolva Törnberg, Head of Sustainability at Fjällräven

When I was reading about the collection there are a few interesting tensions that came to mind. I wanted to ask if the design side and the sustainability aspects ever clash with one another?

I could talk about this for ages. It’s such an interesting and intriguing balance. I think more often than not the two actually build on each other as opposed to being in conflict. The key for us is to have key aspects from a sustainability point of view actually integrated into the design guidelines. First and foremost, the functionality –which might seem obvious but– it needs to fulfil a need. The second part is to create garments with a timeless design. Durability is always a part of making it functional and making it last long but it doesn’t really matter if it’s designed in a way that you get tired of it next season.

We also aways design with the intention of things being reparable. Sometimes that means that a really smooth, hidden zipper might look really nice but it will be super hard to replace if it breaks. There we need to find compromises.

And is there another trade-off between having a brand that’s very focused on history and heritage while also having a brand that’s focused on technological and functional products?

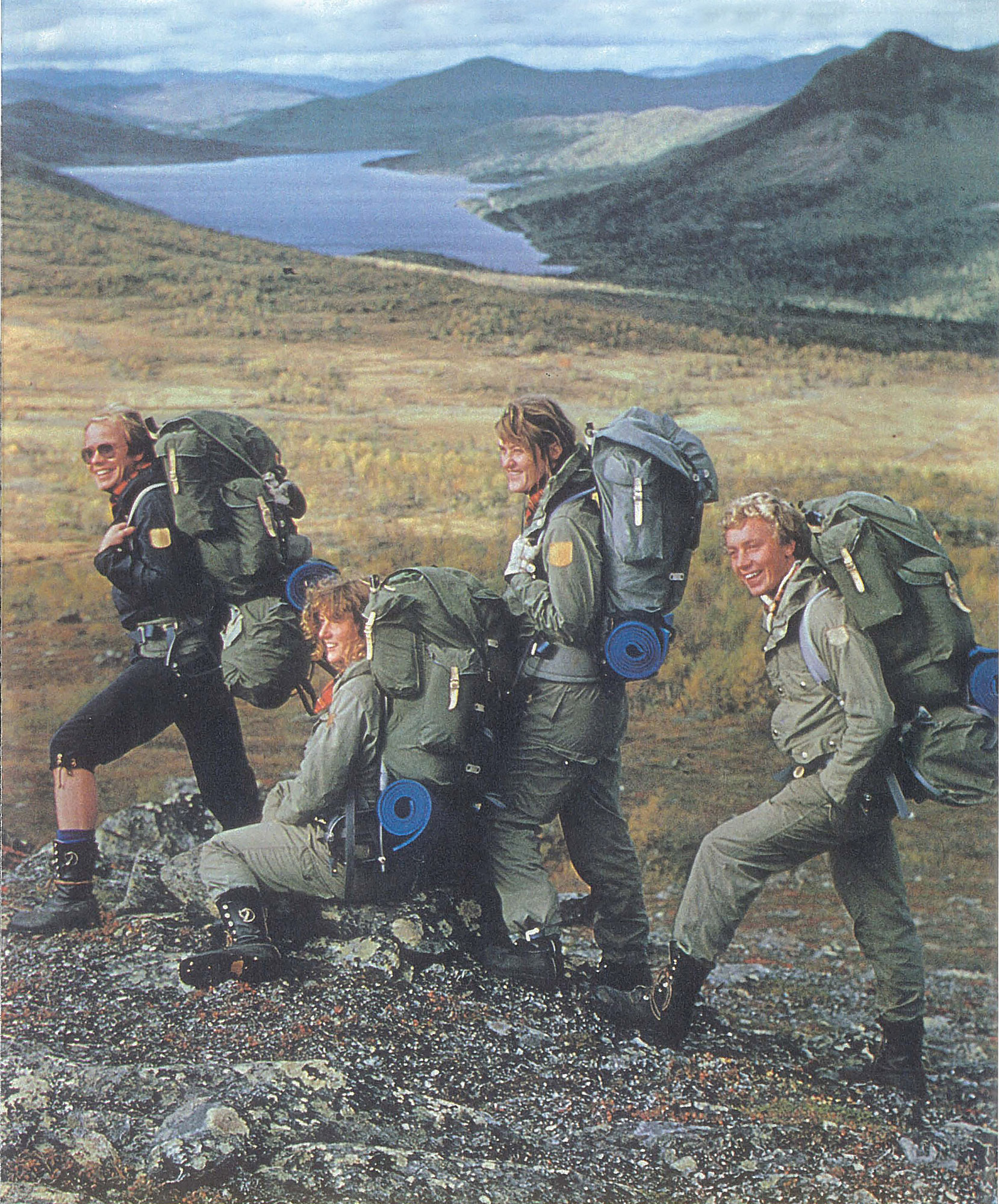

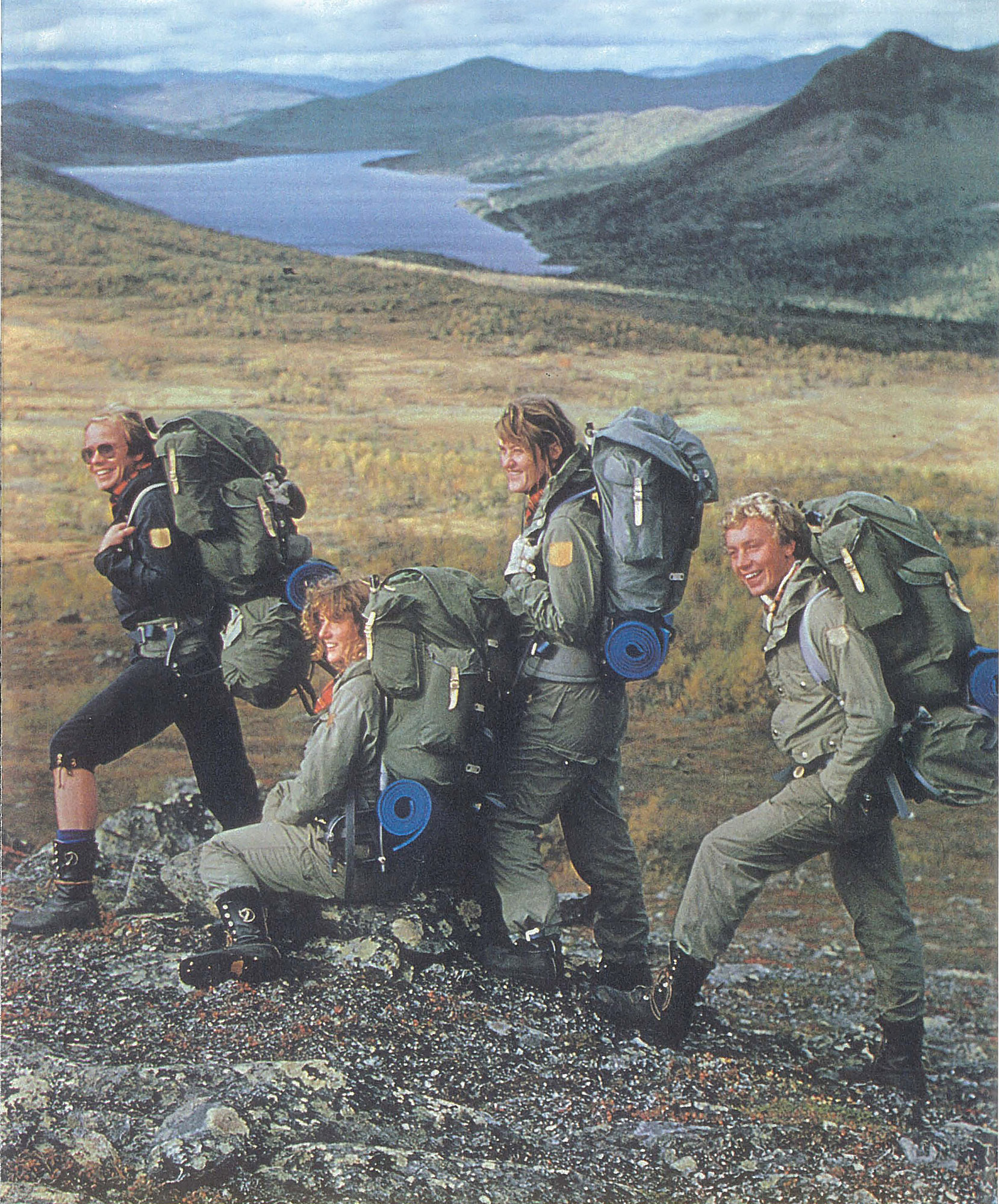

That is something I have to give a lot of credit to our design and product development teams. And also a lot of credit to the field testers. We have a big group of people all of whom make their living by spending time in the outdoors and they feedback a lot to us in terms of features and functionality. I think that those teams together have managed to crack the code of how something technical doesn’t necessarily have to look or feel super… high tech.

Like the super high-tech, hiker-core stuff?

Yeah exactly. Like we work with the Swedish Mountaineering Association and those guys and girls are experts and have been on the mountain A LOT. And their feedback tends to be ‘make it even simpler’. Technicality doesn’t have to be complex. It can be technical in its simplicity.

Less is more?

Exactly!

On that point of demanding the best from your clothing, in Ireland people are essentially being forced into the outdoors because of the current lockdown restrictions. I’ve found that you end up relying on the technical aspects of your clothing in ways that you wouldn’t have before. I’m wondering whether the last year had an affect on how Fjällräven think about making clothes?

Yeah we’ve observed the same thing here. I’m not happy about pretty much anything regarding the current situation but the fact that people might discover nature is nice.

What we are looking at a lot is the question of how can we be as inclusive as possible? That’s something we’ve had as one of our core values for a very long time. Meaning, not necessarily creating products that feel super complicated or talking about spending time in nature as if it’s a life or death situation. “You need all this gear to be able to do it”. Instead we just want to say “just get out there and you’ll be fine if you layer up a bit”. For us it’s about showing tips and tricks to a wider audience that might not be as experienced and to do all of that in a way that doesn’t feel intimidating.

We’re at an interesting point in culture because we’re starting to value premium materials and sustainability a lot more. In Ireland though as much as that is the case, people are always very skeptical about spending a lot of money on clothes.

I think anyone should regard any purchase of any product as an investment – and hopefully as a pretty long term investment. One of the problems from a sustainability point of view is that we don’t necessarily see the whole price on the products we buy. That is to say, not just the price that we pay with our wallets but also the materials and the production processes that go into the product. I think we need to look at the cost in terms of the entire life-cycle of a product.

So like a cost-per-wear approach?

Yeah, a cost-per-wear thing. I heard someone say that it’s better to cry now rather than cry later. I actually have my grandmother’s old Fjällräven jacket, it’s literally hanging up here on my chair. I usually talk about that from a sustainability point of view. Everything we do has an impact and the more ‘wears’ it has, the better distributed that environmental impact is and it’s exactly the same with a monetary impact. Whatever you choose to invest in, you have to make sure it’s something that will last you a long time. You want a garment to solve many of your problems.

Whatever you choose to invest in, you have to make sure it’s something that will last you a long time. You want a garment to solve many of your problems.

I’m really interested to hear about your thoughts on the current hiker-core/gorpcore boom in fashion. A lot of the heritage hiking brands that even 5-10 years ago would have been seen as clothing for hiking nerds are now being worn by Frank Ocean etc. There was an article in the Wall Street Journal about gorpcore that kind of went viral, have you come across it?

You know, in Sweden, we had the Expedition Down Jacket that we’ve had since 1974 and sometime around the 80s a similar thing happened. This really heavy jacket (it was created literally by sowing two jackets into each other) this MASSIVE piece, was all of a sudden all over the place in the hip downtown areas of Stockholm where realistically, you would never, ever need it. Like you could only ever wear it with a t- shirt underneath.

But I think you’re right, it’s interesting to observe. With us, we’re so busy thinking ‘how do we get people out in nature’ that when things all of a sudden get trendy we are a bit like ‘hey, what happened here?’. We have explicitly outlined in our company philosophy that we are not about fast-moving trends, we are timeless and we walk at our own pace. If positives come out of movements like these, that’s perfect. If people start thinking ‘hey, this hanging out in nature thing seems like a good idea’, that’s great!

So no hip hop collaborations to be expected from you guys in the next few months?

Hahaha, never say never.

I think the last thing we need within the outdoor community is to be adding some sort of exclusivity into what is the right or the wrong way to be spending time in nature.

Another trend that’s emerging–partially because of Covid– is that people are spending a lot more time in the outdoors. We have become a nation of sea swimmers…

[Laughs] I know! What’s up with the winter swimming? It’s the same here!

It’s amazing. I have to say, I’m so proud of us. Even two years ago, if you said that you swam in the sea in the autumn, let alone in the winter, people might look at you sideways and think you’re a weirdo.

I know! And it was the same here. But now people are posting pictures of their winter swimming constantly. I was reflecting a bit on this recently.

What might be part of it is discovering different ways of spending time in nature. The more different people that do that, the more different types of activities will pop up because not everyone loves just slowly walking along a trail in the forest.

I am so for that. I think the last thing we need within the outdoor community is to be adding some sort of exclusivity into what is the right or the wrong way to be spending time in nature. As long as you don’t leave anything behind but your footprints, spend as much time there as you want.

From a sustainability point of view as well, it is proven with a lot of studies that the more time you spend in nature, the more likely it is that you will be a part of preserving it. To me, the more time people spend – whether it’s swimming or biking – the more they will think ‘hey, I think this is kind of nice’ and will want to make sure it remains available and sticks around.