Photographer in Focus: Rich Gilligan

Words: Ellius Grace

Photography: Rich Gilligan

You’ve probably seen Rich Gilligan’s photographs before. Maybe his quiet and honest portraits in T Magazine, i-D or Dazed, or maybe his meticulous studies of international skate spots in his book ‘DIY’. I found Rich’s work at a formative time in my life, in art college while I was flailing around trying to find my style. He taught a two week photography course in NCAD where I was studying and I was then fortunate enough to assist with him in the following months. In that time, Rich instilled in me his values and approach to photography, something I would end up wholesale mimicking for a year or so until I eventually found my own path.

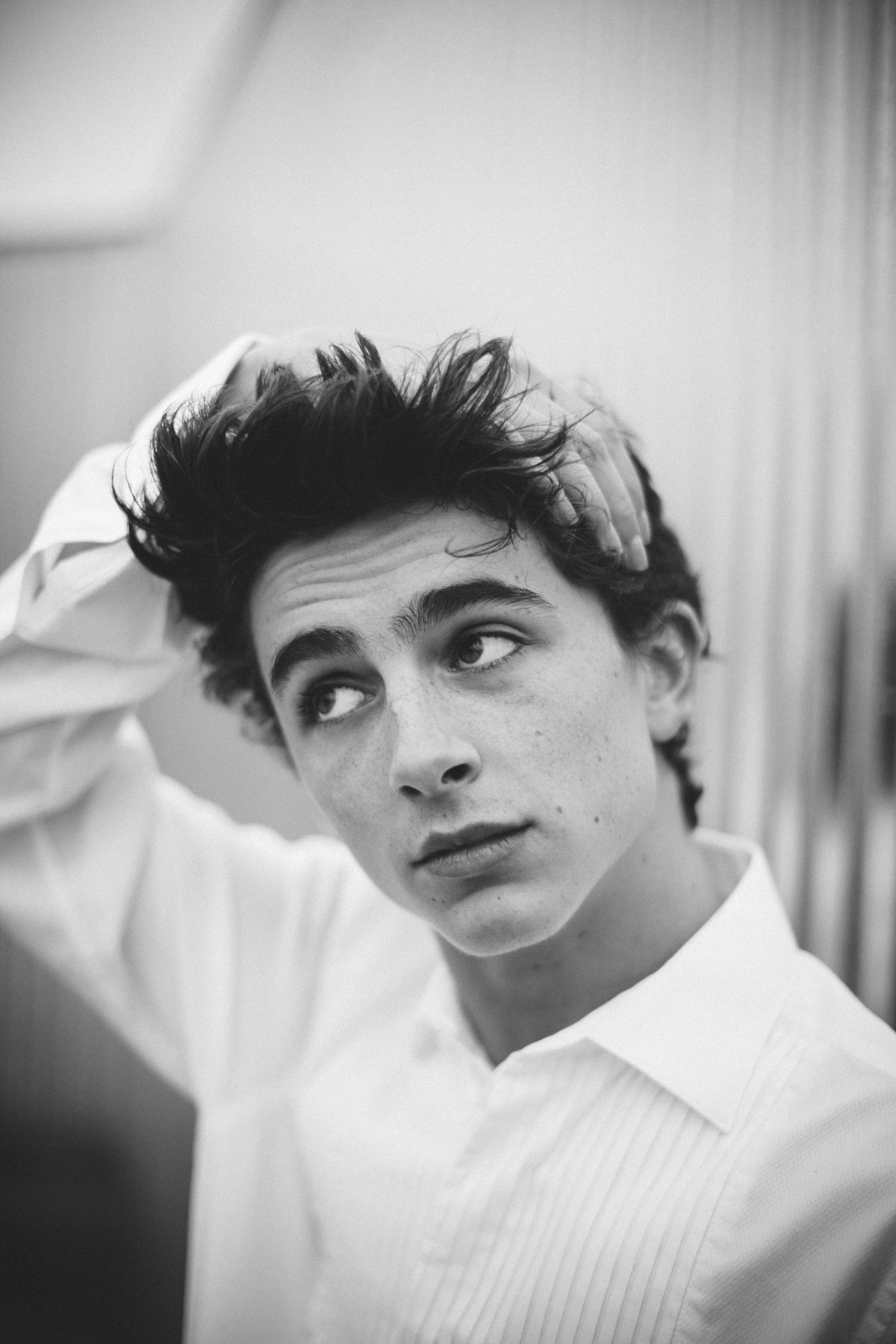

These values are centred around honesty and truth, approaching portrait photography as a collaboration between subject and creator. Rich approaches each subject with an open mind and a large dose of empathy. This idea had a profound effect on me and it changed the way I approach photography to this day.

Despite being a prominent practitioner in Ireland, both in the editorial and commercial photography world, Rich and his family packed up their things and moved to New York City at the start of 2015. In search of a change of scene and the promise of greater potentials. The move was a reaction against comfort, towards a great unknown. This is a common theme for the Irish population, a great exodus that is so often spoken about. While Rich has made the move across the waters, Ireland is still very much a part of him. Mainstays like Cillian Murphy and Aiden Gillen, and more recently Barry Keoghan, have shown up as

his subjects, and even though his daughter Robyn has developed an American accent, she’ll always be from Dublin.

Having just moved back to my hometown Dublin from London myself, nationality and base have been prominently on my mind of late. The fact is that for many Ireland doesn’t offer enough work in their chosen field, but I believe Ireland will always be a returning point for many who were born here. No matter how much we bitch about the weather and how Bono is a pox, Ireland will always be in our blood, no matter where we position ourselves. The Irish stamp is one that most of us wear with pride, and I couldn’t be happier that I spent my formative years here. I’ll move away from Ireland in time, much like Rich, but I know like many others I’ll be back here again. So here’s to anyone who’s had to reinvent themselves and change scene. And here’s to Rich Gilligan.

How did you come to photography?

I guess, I first discovered photography through printed media, essentially skateboard magazines from the early 90s. I can remember distinctly being in Easons on O’Connell Street, with my Mam, and seeing a copy of Thrasher. I was just totally drawn to it. I had gotten a skateboard at that time and I was really into it, but I didn’t know any skaters, or anything about the names of tricks. I got my Mam to buy it for me and I was totally obsessed with it. I don’t think I was even aware of my interest in the photos, it was just the subculture, the clothes people wore and the music that was in it. Everything about it was so alien to suburban Dublin.

I can remember distinctly being in Easons on O’Connell Street, with my Mam, and seeing a copy of Thrasher. I was just totally drawn to it.

Rich Gilligan

So I started cutting magazines up and pinning them to my walls, making these collages of work on my bedroom wall as an 11 year old. And then I started drawing pictures of the skate photos, the whole way through school I’d be sketching skate photos as my art projects. I remember stealing my Dad’s camera when I was about 13 or 14 and going out to try and take photos with my friends. It was just us skateboarding in schoolyards around Dublin and the area we grew up in. After a while, I bought my own camera and started taking portraits of friends, trying to learn technically how to shoot skate photos too. I remember distinctly going to the local library and looking for a photography section and finding a book by Dwayne Micheals, this American photographer with lots of weird double exposures. It was the first time I’d seen work that made me go, ‘oh wow, this is an art form as well, it doesn’t have to just be purely functional’.

So skating brought you to photography, but do you think being part of skate culture had an effect on your approach to photography?

I think back when I was in my early to late teens, being a very different time in skateboarding and in Ireland in general, you were definitely an outcast. Skating wasn’t cool in the way it is now. With the likes of Palace and Supreme, and even big companies like Nike, Adidas and Converse, skateboarding is big business now, whereas back then it was really small and independent. And Dublin back then as well, it was a very small-minded city. You’d get verbal and physical abuse just for looking totally different to everyone else. So I think looking back on it now, I probably always had this determination to put up with all that shit and still to not care. Just to be like, ‘I’m just going to do this as a fuck you to everyone out there’. So that definitely shaped my approach to photography. To be a skater, it takes a lot of time and perseverance. It can be really painful, you hurt yourself a lot. You can’t fake it, so I had this drive from that.

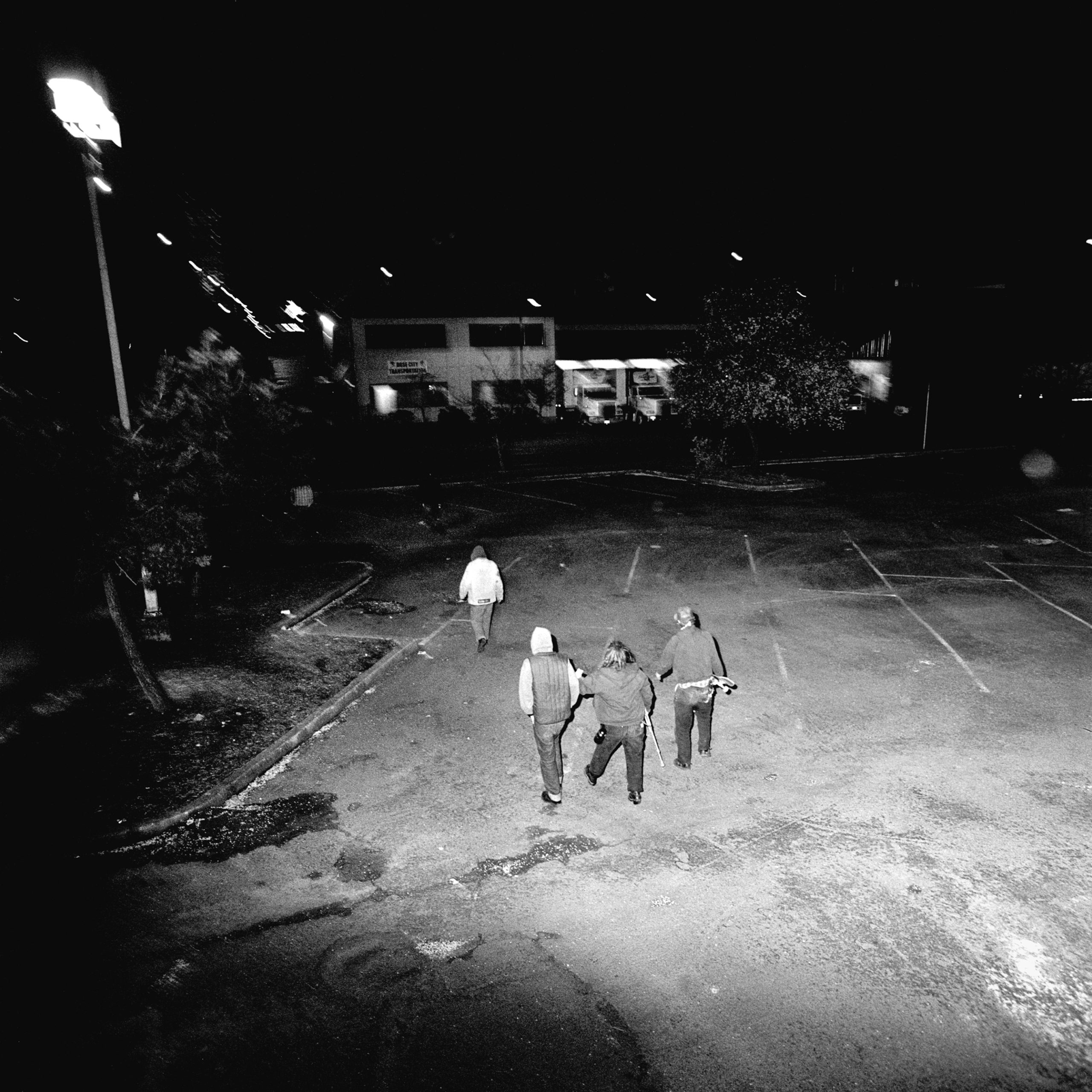

Back then in Dublin I think there were 30 people in the whole city who skated, and you kind of knew most of them. If not by name, you’d know that’s the guy who can do Caballerials on Baggot Street. People would just give each other the nod and again it was such a small little circle that as I got a bit older I found myself going into the city every weekend, camera wrapped up in a hoodie in my school bag. Because I was the only person taking skate photos and documenting it, people really opened up to me. I was the guy who if I took a good photo and sent it to Sidewalk in England, there was a chance they’d run it. So that worked to my advantage, as I got my technical skillset down early on. That meant I could start getting work published, and that was just really exciting. I still get excited about seeing stuff in print, but back then, the concept that I could take this picture of one of my best friends, and that a magazine in San Francisco would run it as a double page spread with my name and his name in it… That was completely mind blowing. I think growing up as a skater toughens you up. You know how to handle yourself, not just physically, but that you know how to read situations and you’re quite street wise because you’re probably used to dealing with lots of shit. So that stands to you because so much of photography is knowing when to push and pull back. Not being too pushy but at the same time not being afraid to get the pictures you need to get. It’s definitely a good school to come from.

Something that you taught me is to be part of the thing you’re photographing. It was something I struggled with for a long time, seeing these really personal stories and asking ‘how are these people letting the photographer stand right there?’, and then I realised that the photographer was part of the situation.

Sometimes that awkwardness, the anxiety and how misplaced a photographer is in a situation, sometimes that’s the strength of the work too. I think there’s always a point while I’m making work, where whatever it is I’m shooting, there’ll be this moment when I realise I’m completely invisible to whoever or whatever I’m shooting. And that’s when I think the really interesting pictures start to happen. You’ve broken through this barrier. The last thing I want to be is too pushy or intrusive, and there’s lots of work out there where it’s really obvious that it is exactly that. There’s no real empathy toward what they’re shooting, they’re just taking what they can. I think I definitely like the collaborative process of making work. And that’s not just with personal projects either. At this stage of my life I do more commissioned work than personal work, and I’m constantly trying to find that balance between the two. It all feeds into each other, so the way I shoot a commissioned editorial portrait or a fashion job, I still treat people on the same level.

I think being able to feel that trust with people, that’s a skill that you really have to learn. It really comes through in the images, when someone’s at ease. Taking the photo is such a small part of the process, there are all these other external factors that come together to create this authentic moment, without it being forced or overly obvious.

It really is that adaption that you have to go through that makes a professional photographer. Nothing to do with equipment or gear. Being on your toes on a daily basis, it’s very reactionary.

Some people work in a very scientific, almost clinical way though, and that works for them. Whereas I work from instinct a lot. You have to be fast, you have to adapt really quickly. And that’s one thing that I’ve realised in the last few years, and even working here [in New York]. Growing up as a skate photographer, you have to work so quickly, and a lot of the time you’re making work where you’re not meant to be. You’re waiting on the cops or a security guy to kick you out, so you’re on your toes, looking over your shoulder as you focus, and you’re watching the light change as someone’s approaching a set of stairs. You’re trying to calculate all these things into one frame, one moment, and I apply all that to a fashion commission. Dealing with a model and a stylist, hair and makeup team and a client and an art director. You’re in the eye of the hurricane, but you can somehow use that energy to your advantage, and create something that’s very authentic, and has a real sense of moment instead of it feeling very staged, which I really try and avoid when I work.

You’re in the eye of the hurricane, but you can somehow use that energy to your advantage, and create something that’s very authentic, and has a real sense of moment instead of it feeling very staged

Rich Gilligan

So you’ve been living in New York for a while now. What is it like to come here and be working as a jobbing photographer? And do you think Irishness has had an effect on the way you’re experiencing this?

Moving here definitely felt like completely leaving our comfort zone, and I was at a point with my work, and it was the same with my wife Petria, we both felt like we’d achieved a certain level of work in Dublin, and hadn’t really had to hustle too hard for a few years because there was steady work coming in. I was really grateful for that, but I had a really niggling feeling in my gut, I really wanted to push myself out of my comfort zone and go somewhere where the stakes are higher.

There’s so much work here, but also so much competition, it’s such a competitive place. But at the same time there are opportunities here that just don’t exist in Ireland right now for us. Long term, we’ll probably go back, but I feel like we were both at a point where we had to leave to feel like we were progressing in a positive way. We didn’t want to end up getting stagnant and bitter, feeling like we should be doing better work. The usual shit that everyone says. For us it was a lot scarier because we were doing it with a one year old in tow. It wasn’t like one of us was coming to a real job here, we’re both creative working freelance, so we literally moved here with money we’d saved up by living with our parents for the last six months in Dublin to cover the first leg of our journey here. I’d built contacts here and had meetings with agencies.

The hustle is intense here, it’s real. It wasn’t like one of us was coming over to a cushy job with an apartment lined up and health insurance sorted. It was scary. The first six months, the first year, even still, it’s a real rollercoaster. It’s high highs and low lows, but there have been real breakthrough moments where you get a commission for T Magazine, New York Times. Suddenly you’re flying to Chicago to do a portrait with Irvine Welsh, and you’re literally like ‘Holy shit, how did this happen?’. And then there’s also months looking at the bank balance wondering how we’ll pay the rent next month. Something will give or come through, though.

There are moments where you feel like you’re mad, what were we thinking? Was this just some crazy idea that got out of hand? Some pipe dream? Then you realise you’re not mad, and it’s just a process.

I feel like whatever happens, or however long we’re here, I’m just so grateful that we have this opportunity to be here now. Even for my daughter Robyn, in her head it’s totally normal growing up here, that we live in this tiny apartment in Brooklyn. We’ve met some amazing and inspiring people, that are doing really brave things with no guarantee.

In terms of being Irish here, and that experience, I think it definitely helps, without a doubt. There’s just such a rich history of the Irish coming here, and people have so many routes. Before I moved here I was quite cynical about it, almost a bit dismissive, ‘the yanks are telling me they’re Irish. You’re not Irish’. But now I live here, and my daughter is a three year old in pre-school with all her friends that have really cute American accents. If you ask her where she’s from, she’ll say she’s Irish, so now I have this real appreciation for it. The people who have come here, it’s not an easy thing to do, and it’s scary, but there’s an openness here that I feel is really unique, and an optimism that I know is such a cliché, but it’s a can do attitude. It’s cutthroat as well, America is such a walking contradiction in so many ways. But I do find that really inspiring.

I feel like it has affected how I work, it has affected everything in general. There are times when it’s really tough, but the flip side of it is that sure you’ve got the Irish card, and if you go and meet an art director or an agency, they’re more likely to remember you for one, your accent and two, we have an ability to communicate with people. We can explain a narrative to someone in a way that’s probably more interesting than lots of other people for some reason. People can relate to it, and you can use that to your advantage. At the same time, New York City is the biggest melting pot on the entire planet. So no one really gives a shit. What’s great about it is you can be whatever you want here.

It’s so important to be people facing for photography. It’s such a human facing job.

When I first moved here, I found it really hard to make personal work, because everything feels like you’re in a film. It’s this heightened sense of reality, where everything is really poetic and beautiful. Or even that the light is so different that you’re wondering if these pictures even matter. Is everything so iconic here that it’s impossible to find your perspective. But then you quickly realise that the bigger story is always about smaller stories within it. And that’s how I try to navigate that.

So you teach as well as do commissioned work, is there one thing that you tell your students every time?

Honestly, and this probably sounds so cliché, but I feel like I almost get more from teaching than I give. I learn about work that I mightn’t have been aware of, and it forces me to really know my shit, to be tuned into what resonates with people at this point. For me, the key thing I try and get across to them is that the technical side of things is never the most important thing. I find with a lot of students that they’ll be really obsessed with the technical. And that’s good because it’s good to know how things work, and have an understanding of the craft. But it’s gone full circle now where some people are so obsessed with the camera or the equipment, or the fact that it’s analogue or it’s not analogue. It’s not really about any of that, it should be about the image, and about what resonates from that. I think the key thing is to find your subject matter, find work that really resonates with you, it’s nearly impossible to not follow trends, but you should find what you want to do and stick with it. In time, people pay attention.

There’s such a small percentage of people who really can make it in photography. I think about how many students come out every year, from colleges and masters degrees, all over the world, where the number of actual photographers commissioned seems to just shrink every year. People have to be extremely self-motivated if they want to make it. You need really strong self-belief, because there are no guarantees. If you’re willing to put in the work and you find your voice and it’s interesting, people will listen to it. So just keep going. Persistence is key. A lot of it is about the work, but it’s also about the right person seeing the work at the right time. That opens one door, and that gives you the keys to 10 other doors you didn’t know existed. Stay humble, and don’t be a dick.

Words to live by.

Yeah, that’s my mantra for life.