How a Finnish Street Artist Bottled Irish Folklore

Words: Stephen Burke

Photography: Marko Rantanen

Artwork: EGS

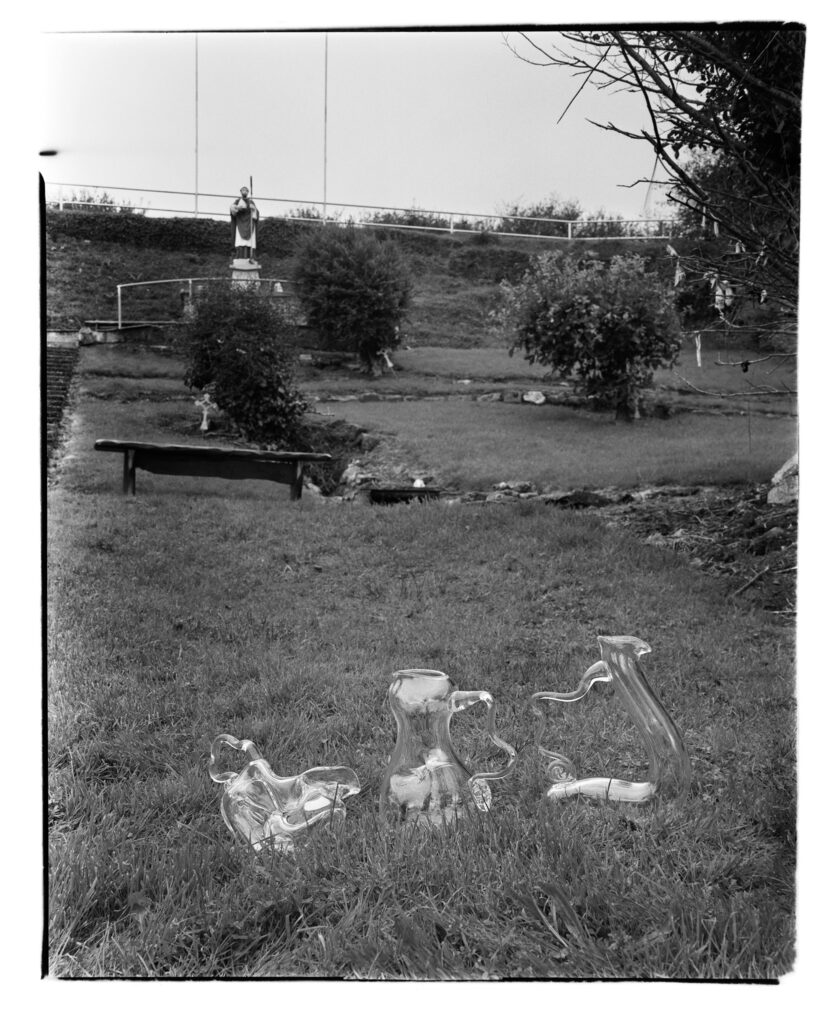

A few months ago we found out that acclaimed Finnish street artist EGS was going to be travelling to Ireland in order to visit three holy wells. EGS was assigned a very particular –and delightfully whimsical– diplomatic mission. His job was to work with local craftspeople in Kilkenny to create three bespoke glass vessels which would then be used to transport the water from these wells back to Finland.

As part of our partnership with Irish Design Week, we commissioned Stephen Burke of Post Vandalism to find out more about this story that caught our imagination.

I first came across EGS’s work within the graffiti scene. Originally from Helsinki, he began painting in the late 1980s as part of Finland’s first generation of graffiti writers and is now one of the country’s leading artists to emerge from that movement. While many graffiti writers follow a well-trodden path into painting when entering the art world, EGS has carved his own route, working primarily in sculpture and, most notably, developing a glassblowing practice where he abstracts his graffiti alias E-G-S.

That drive to go his own way is reflected in his travels around the world in search of hidden walls to paint, a spirit deepened by the Cold War boundaries that once surrounded his homeland. It’s given him an openness to step beyond his comfort zone and create in unfamiliar conditions, a quality at the heart of his practice.

Most recently, it led him to Kilkenny, where he drew inspiration from Kaj Franck, a key figure in Nordic Modernism who visited Ireland in 1961. Franck’s report on Irish design later inspired education reforms and the establishment of Kilkenny Design Workshops. EGS’s own trip treads lightly in those footsteps, on a glassmaking pilgrimage that was facilitated by Jerpoint Glass, where he responded to the folklore of three local holy wells: St. Moling’s, Kenny’s, and St. Augustine’s. Along the way, he also allowed for detours, exploring abandoned sites and leaving his mark on the journey.

These new glass works, along with a documentary and accompanying zine, will be presented at this year’s Irish Design Week, and I was lucky enough to speak with EGS about his time in Ireland.

I’ve heard you speak passionately about exploring new places in previous conversations, it’s clearly something very dear to you and is a big part of the spirit of your work. How did you develop this adventurous outlook and how was your experience coming to Ireland and exploring Kilkenny? One of your project aims was to get lost along the way and create a new map, well, did you?

Travelling has been a big part of my artistic practice since the beginning. As an aspiring graffiti writer in Helsinki in the late 1980s, I explored the city looking for tags and pieces. I kind of mapped the city through graffiti — it became my way of navigating. Later, when I started painting more myself, it was like drawing a map. I first painted in Helsinki, then began travelling abroad to Stockholm, Copenhagen, and around Europe to paint trains and walls, and to network.

Everything was analog — a lot of footwork, letters, photos traded by mail, stamps in passports, phone booths, and phone numbers of people you never met but knew because they wrote graffiti. I drew a map of Europe based on my graffiti-writing experiences in the 1990s. Nowadays it’s much harder to get lost, at least physically.

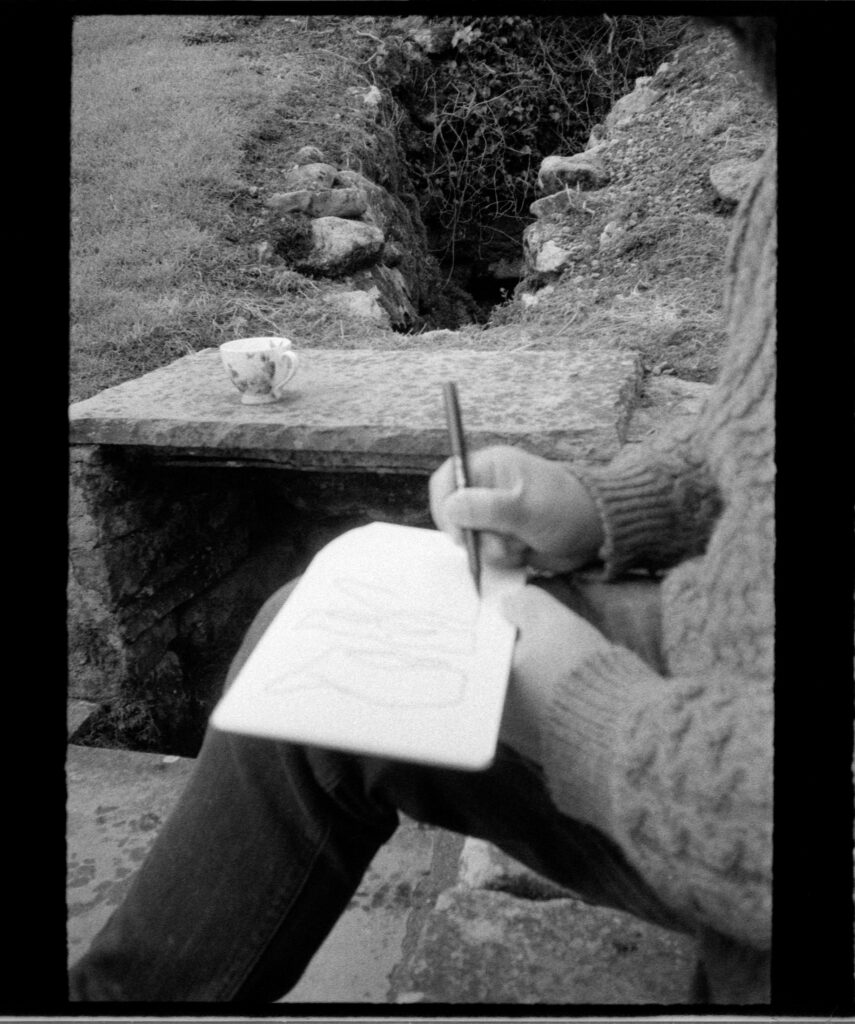

Kilkenny and its surroundings were an amazing experience. Photographer Marko Rantanen and I did our best to get lost and find something unexpected. I drew maps of our routes afterwards — they’re about the feelings of movement, the gestures of travelling, and the wish to be lost.

This connection you have with Kaj Franck is fascinating. His visit to Ireland in the early 1960s and the report he produced afterwards helped reshape design education here. You’re coming from a different angle too, bringing a graffiti ethos into glassblowing — this subcultural perspective in craft is quite unique. How do people from the craft and graffiti communities respond to what you’re doing?

I think the craft and graffiti communities have a lot in common. People in both do their practice with talent, heart, and tradition. Both are often overlooked by the mainstream art world. Many don’t think, or even want to think, that they’re making “art” — they just write graffiti or blow glass. They’re like guilds or secret societies that protect and pass on their skills.

Teamwork is common in both worlds. The deeper you go into the practices, the more finesse and nuance you find. Both carry a strong sense of pride in tradition.

Whilst in Kilkenny, you produced new glass work with Jerpoint. How was your experience there, and what kind of facilities did you get to use?

I had a great time at Jerpoint Glass with the talented and welcoming Leadbetter family. I visited wells with Rory Leadbetter — I sketched on site, and we talked about the wells, their surroundings, and the stories behind them. In the following days, Rory and I worked together on a series of vessels inspired by the three wells. Rory was blowing, and we were shaping and sculpting them together — improvising, experimenting freely around my sketches.

We also used birch ash from a Finnish sauna, a method Kaj Franck once used to create bubbles and texture in clear glass.

When you’re working with a material as fragile as glass, do you ever feel that same sense of improvisation or risk that exists in graffiti? How do those instincts translate across materials?

They are very similar in my mind. Both are fragile — glass can break easily, graffiti can be washed away or destroyed. Both involve risk, adrenaline, and quick decisions. There are challenges in the process and constant creative compromises.

Graffiti is often painted at night, and you only see the finished piece in daylight the next day. I find it very similar to glass — seeing the work come out of the cooling oven in the morning is always exciting and full of surprises. Both are also about teamwork. You have to trust your company in the process.

You visited three wells in Ireland, St. Moling’s, Kenny’s, and St. Augustine’s. These sites are steeped in history and ritual. Whilst there, you used your glass pieces to collect and hold holy water from the wells. The containers themselves play such a key role in the work. Did the shape or atmosphere of the wells influence how you designed the glass works? Do you see them as utilitarian or sculptural? What did you do with the holy water then?

I sketched in situ. I tried to draw the wells into my three letters, and from those letters into three vessels — that’s my language for describing how I see and experience the world. They also carry shapes and references from local mythology. They are functional and non-functional at the same time — they can hold water, but also memories, folklore, and dreams.

Folk traditions are very much alive in many places. Even tagging has recently been described as a modern folk practice by author Sophia Kingshill. Do you see your act of collecting holy water as part of that lineage, a continuation of folk ritual through contemporary art and design? And in a time when most people experience the world through screens, can projects like yours help us feel connected to the land?

I like things that are physical. The project is photographed by Marko Rantanen on film. Graffiti itself is a ritual for me — I feel part of a great tradition of graffiti writing, and I include that folklore in my work and mix it with others.

Meeting people and working with them is important, especially now when most communication happens through screens. I want to leave my mark in the physical world.

The works you’ve made while in Ireland will be presented at Irish Design Week in collaboration with the Finnish Cultural Institute. This will include the glass works, a documentary film about the project, and a zine. How do you imagine these works coming together in that space?

It’s teamwork between me, glassblower Rory Leadbetter, photographer Marko Rantanen, and graphic designer Tom Backström. The goal is to create a small vacuum that combines graffiti, glassblowing, holy wells, folklore, adventure, detours, beauty, mysteries, and maps. I don’t really want to give answers — only hidden hints to spark everyone’s imagination. Analog dreams in a digital world.

Stephen Burke is an artist, curator and writer specialising in graffiti and contemporary art. He is also the founder of Post Vandalism, an internet platform dedicated to artworks that explore the aesthetics and concepts of graffiti and protest. His debut book is out soon.