The District Development Plan

Words: Dylan Murphy, Ellen Kenny, Shamim de Brún, Ciaran Howley

Artwork: Jan Walsh

Last February, Dublin City Council began work on the Dublin City Development Plan 2022-2028. It intends to establish a framework for Dublin City that “improves the quality of life for citizens” while also making the city “a more attractive place to visit and work.”

Given the current malaise of the capital and Ireland more broadly, it arrives at an important juncture, especially when the issues are painstakingly apparent. There’s not enough sufficient quality housing, culture is dying and we’re in the midst of a climate crisis. What makes all of this more difficult is the pervading sense of hopelessness. Conversations are reduced to cul-de-sacs that ruminate on the problems and there’s rarely much attention given to solutions.

This is where the District Development Plan comes in.

This summer, the Dublin City Development Plan entered stage three, and the Council invited residents of Dublin to submit their own suggestions of how to improve the city. With this in mind, we sat down with Dublin-based experts in housing, transport, culture and climate to collaborate on solutions-based approaches. We’ve defined the biggest issues facing our city, what is causing them and the potential solutions in an alternative plan of our own.

Many of the issues are complex and require imaginative thinking. We can’t begin to feel optimistic if we can’t envisage what an alternative future looks like.

Likewise, we can’t put people’s livelihoods at risk by being fiscally irresponsible. That’s why we asked our guests to design solutions that draw from other forward-thinking countries as well as our own past. We’re not trying to reinvent the wheel, just build a better car.

Through our consultation, District has created a plan to reimagine Dublin city as a sustainable landscape. Imagining Dublin as a place that provides everyone homes, creates vast infrastructure, revives its cultural personality and counteracts the climate crisis all at once is hugely idealistic and ambitious. But it is possible, and we can do it.

Housing

When it comes to looking at how people can live in a city, we have to first look at where they will live.

We’ve all heard the statistics before. There are currently over 5,000 homeless people in Dublin. Simultaneously, Dublin City has the second highest proportion of vacant properties in Ireland. The average monthly rent is €2,153 and there are fewer and fewer homes available on the market. The problems are heard loud and clear but what are the solutions?

To Professor Rory Hearne, the plan to improve housing in Dublin is two-fold: build more social housing and edge huge real estate developers out of the city. According to Rory, Dublin has let big real estate investors and “corporate landlords” dominate the housing supply.

“Ireland essentially allows the private market to be the main provider of housing,” Rory explains, “And what that means is that a very low proportion of our housing is social housing or housing that’s affordable from outside the market.”

Rory explains that one way to limit the dominance of private developers is to cap the amount of rental properties they can build before selling them to residents. A more radical suggestion, however, is the mass implementation of social housing to edge out vulture funds.

“If we prevent investment-focused property developers and vulture funds taking over, we clear up space for social housing, and space for people who see the house not as an investment, but as a home.”

There’s a stigma attached to social housing that anyone who lives there is lazy and greedy. Because the average Irish person sees property as a commodity, as something to drive your own wealth, social housing is perceived as something to be ashamed of. But Rory explains that cities without this stigma thrive under social housing.

“If you look at successful countries that provide housing, it’s countries like Austria. Half of all housing in Vienna, their capital city, is provided by either the local council or by what they call not for profit housing associations. They’re provided on an affordable, subsidised basis.”

“They are really high quality homes. There’s no stigma attached to them. People of all incomes live in them, and they’re really well planned, really well designed. People want to live in them.”

Compared to Vienna, only ten per cent of housing in Dublin is classed as social housing. In the first half of 2022, the Council met a mere seven per cent of their target to build more houses.

Right now, social housing is on too small a scale to make a difference, but we have the ingredients to success right in front of us. As Rory explains, groups like Clúid Housing, Respond, and the Housing Alliance have the skill and dedication to provide affordable housing. We just have to give them the resources they need.

“It’s astonishing when you read [the Dublin City Development Plan] in detail to see the extent of public land and private land that is actually available in the Dublin City area. Numerous land banks and large sites are available,” Rory tells us, “I think that’s really where the public should get involved: make a submission to Dublin City Council and call on the council to build affordable homes that are sustainable.”

Derelict housing is often cited as an obvious solution, but John Macken, Associate Director of O’Mahony-Pike Architects says the potential hazards and the cost of redeveloping means they aren’t a realistic solution. Instead, he asserts that the space for these new builds is already there in areas like Dublin Port and just requires expansion. While the conversation around the Port has been allowed to fester and die out due to lack of compromise, John is convinced it provides the perfect area to expand into with new housing.

Citing the example of Nordhavn, a former industrial shipyard in Copenhagen currently being expanded to create more land for high density housing, he says it’s the ideal model to emulate. Since its inception ten years ago, it has housed 5,000 people, and by 2050, it will house 40,000 residents. It is lauded as “one of the most sustainable projects in the world right now”. We have our own Nordhavn sitting right by the Irish sea.

Aaron Nolan, communications director of the Community Action Tenants Union (CATU), agrees that making way for new, affordable housing is an essential part of Dublin’s future, and a way to counter vulture funds in Ireland. According to Aaron, if the Council actually meets its social housing target, it will lower the price of housing overall. As private developers are “only following where [housing] is most profitable”, creating a space for non-profit homes will drive the private market lower, or drive it away altogether.

Aaron referenced the State drive in the 1930s through to the 1950s to turn “squalor” tenements to vast social housing. If we lived in a “golden age of social housing” before, we can again. “It challenges the classist nature of housing where there’s ‘working class people here and rich people there’. It’s a much more pleasant way to live.”

Reimagining how we finance these houses and where we build them also entails reimagining just exactly how we build houses for a better Dublin. John explains that to house enough people, we need to change the ideal image of a house: “right now we’re assuming apartments are for rental or for short term stays.”

But John emphasises that we need to change our traditional “fractured mentality” on what a home can be: “I think the idea of the front and back garden, the three bed [semi-detached house] is still ingrained in our culture and it needs to leave.”

The departure of the large semi-detached house ideal can be replaced with duplexes, high density housing, high-storey apartment buildings, and quality terraced housing, John explains. We see this in cities outside Ireland, like Accordia in Cambridge, a development with vast collective gardens and beautiful courtyard areas. But we also see it in Dublin already. Stoneybatter is already known for high density, high quality housing, and as John simply puts it, “it works”.

High density urban living is the way of the future, according to John: “I think getting those kinds of spaces freed up has to happen. I don’t see any other alternative.”

A new vision for housing requires high costs and high effort. The Irish Government currently spends roughly €12 billion on housing. To put that into perspective, we spend €24 billion on healthcare. To allow authorities like DCC to provide social housing, the State will have to completely restructure their budget, restructure how they tax people and where they put that money.

These changes would also require people to reshape how they view houses and land. As John said, we need to reconsider the ideal structure of a home. But Rory explains that we also need to restructure how we view the supposed monetary value of a house in order to find its true value as a home.

“We have people who own properties, buying more properties, which inflates prices, which locks people out of being able to buy a home,” Rory explains, “And still some people look at houses and say, ‘oh, I’m looking at the value of my house and I want to see it continue to rise’- rather than understanding that actually continually rising house prices is not a good thing because your children then can’t afford to buy a home.”

This “values conversation”, as Rory puts it, is much more complicated than just adding money to a budget, edging out corporate landlords, and building new kinds of houses. It requires a deeper consideration into how we treat an economic touchstone in society.

“The value of property of land or buildings is not their monetary value, not their wealth value, not their value as assets as commodities, which essentially is what they’ve been turned into, but instead as homes.”

A referendum on adding the right to housing to our Constitution could shape this change in values and force the Government and local authorities to take action, as Rory previously explained to us.

Beyond a potential referendum, Aaron believes that joining organisations like CATU can reshape how you view housing and living rights, and it will encourage more direct action and advocacy until Dublin City Council is forced to implement the change necessary.

“Organisations like CATU are seeing huge numbers joining them. It would indicate that particularly young people have had enough. Previously where they could be sent away to the States or wherever else, [young people] are actually finding out that there’s actually nowhere to go anymore and they actually have to get involved in politics or in their communities.”

Transport

How easy it is to move around the city, and how safe you feel travelling, is a huge aspect to consider for the redevelopment of Dublin. Expansive, well-connected public transport is the great equaliser of a good city. As John Macken, associate director of O’Mahony Pike Architects, explains, “Psychologically, it makes a difference, connecting the city together.”

“I mean, in Manhattan the Subway connects everybody. Everybody uses the Subway because it’s the quickest way to get around. So has the effect of connecting people together.”

The first thing you need to do to connect a city through its transport, is to get them out of their cars. According to the CSO, there are 503,726 cars in Dublin. That’s over half a million vehicles causing congestion, harming the environment, and preventing Dublin from efficient connections.

This starts by simply providing better alternatives. Feljin Jose, chairperson of the Dublin Commuters Coalition, described his transport utopia for Dublin: “I would invest heavily in rail infrastructure. More Luas lines, more upgrades to the DART lines. That’s the high capacity transport you need to bring people into the city or from outside the city to other towns. You need that.”

Feljin prioritises frequent and reliable rail infrastructure for Dublin as trams and trains can carry the most passengers in the smallest space. Projects like DART+ and Metrolink are promising but according to Feljin, these projects are taking too long. We need to ramp up our rails, and follow some examples from our European neighbours.

Feljin sees cities like Paris as the template for Dublin’s future. The Paris Metro is one of the largest and busiest underground rapid transit systems in Europe, serving 16 lines and approximately 220km of tracks. Despite being so busy, you rarely need to walk more than five minutes to get to a stop, and trains run every three minutes without fail.

Like Ireland’s Luas, the Paris Metro is owned by one state-company. So we’re already on the right track to copy their example. Paris is roughly similar in size to Dublin, but we have a quarter of their population so we don’t need to copy their scale but we can definitely take inspiration from their model.

Due to the enormous nature of the project, the Paris Metro was conceived as a joint public-private venture, with the expenses and effort split between the French government and the Compagnie Générale de Traction.

A joint public-private partnership looks like the key to organising efficient transport. Some small competition keeps the rail construction competitive and prevents overstaffing on projects.

But the French Government also works closely with construction companies and unions to avoid mismanagement and mistreatment.

If Transport Infrastructure Ireland worked with an ambitious, innovative private company to develop new rail lines in Dublin, we could see an entire system spread throughout the city.

Feljin isn’t keen to keep buses in Dublin, as “it’s not ideal to have that many buses in the core city centre area.” Whereas John argues that we have to work with the system we have, and the Dublin bus network isn’t going anywhere: “there’s different areas where Luas lines were proposed, and they were deemed not viable because there simply wasn’t a critical mass of people in those areas.”

The real answer is somewhere in the middle. Most successful transport networks don’t rely solely on one mode of public transportation and certainly not buses. Just think about Hong Kong’s approach. Residents have access to buses, mini buses, double decker trams, cable trams and most importantly, their Mass Transit Railway which is made up of heavy rail, light rail and a feeder bus service across a multi line rapid transit network. It came as the result of a study commissioned by the government in response to road congestion. The study was released in 1967, with construction beginning swiftly after and the first line was opened in 1979.

No doubt, extensive transport networks take time. Hong Kong’s MTR took thirteen years for the first line to come into existence, but if Dublin had the same urgency and organisation it could have had alternative transport of its own. The Dublin Metrolink was first discussed in 2005. Since then, it’s been pushed back multiple times and at a generous estimate, it’s set to be functional by “early 2030s“, but we wouldn’t hold our breath. That’s not to mention the mooted construction of DART+ which is yet to have an estimated completion date.

At the end of the day, working within the transport framework that Dublin has already is not the answer. We need to move in line with other major European cities like Madrid, Berlin and Zurich. That entails developing additional systems that meet the demands of the city’s inhabitants.

But Feljin provided a cautious reminder that the quality of a rail or bus is only as good as their accessibility. Pedestrianisation is key to creating a sustainable, accessible city: “You either have like 500 people living around a train station, or you can make it easier for people to walk around, and you suddenly have 1000 people living near a train station.”

When it comes to footpaths and walking, John envisions Dublin like Brussels, which recently began a large pedestrianisation campaign. Traffic is now completely diverted to the outer ring road of the city, and entire districts have become car-free in recent weeks. Dublin’s outer roads are similar to Brussels’, and we have already started to pedestrianise streets like Capel Street. What if Dublin rerouted its traffic to the outskirts, and we could pedestrianise entire districts of Dublin?

“I think from COVID a huge opportunity in pedestrianisation happened, and they haven’t fully followed through with that. I think we need to expand it much more. The areas within the canals should be up for grabs, in terms of pedestrianisation and cycle routes.”

Bikes present another opportunity for Dublin that we can embrace. Feljin is confident that “a lot of people out there want to cycle. And the biggest reason people tell us why they don’t cycle is because it’s too dangerous.”

Right now, bicycle lanes in Dublin are rare and dangerous. The average cyclist can expect several liminal spaces where cycle lanes suddenly disappear, particularly at junctions and cars getting in their way even when there are cycle lanes.

Circling back to Paris, Feljin is awed at how, in just two or three years, Paris has built impressive cycle infrastructure and given “entire roads given over [to cyclists].”

Feljin also thinks it’s important that Dublin give more bikes to its residents. Right now, the Bike to Work Scheme helps cyclists save up to 52 per cent on the price of a bike but it is only helpful for people with employers who opt into the service.

If the Bike to Work scheme was offered to residents of the inner city, or students, or just anyone who really needs and deserves it, Dublin would become a much more sustainable and accessible city.

Dublin City has already started working on public transport. More 24 hour buses are arriving this autumn and BusConnects will service more extensive routes. However, we need to get even more inventive. We need to create a city that doesn’t serve cars but serves people.

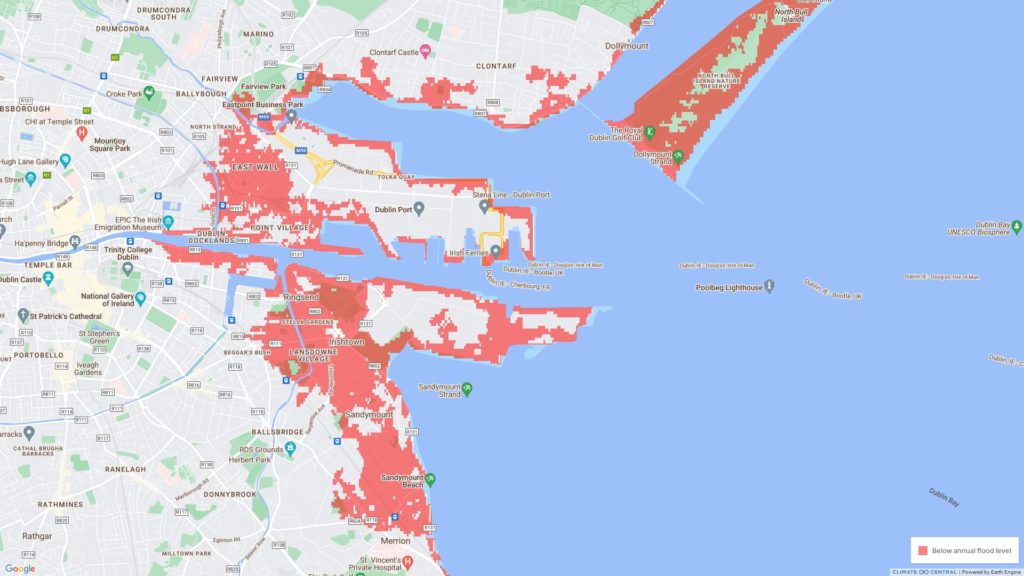

Climate

Of all the concerns in the development plan, Climate Change poses the most immediate, life threatening danger and subsequently it requires the most radical action. Put simply, the problem we face is pushing the earth past where civilisation can function.

Acknowledgement of an issue is the first step in solving it, but reframing how we think about what counts as climate action is equally as important. Climate activist Saoirse McHugh asserts that “any things that would make life better – are climate solutions.”

Instead, Saoirse suggests focusing on “solutions to climate change that are also embedded in our daily lives”. Citing warm houses and well-planned urban areas with excellent transport as factors that facilitate people living more sustainable lives.

We are in the technology age, so of course, new technical solutions need to be looked at, but “there’s also the danger of techno-fixes – who owns the technology and at what cost”. Many out there know there are generations who will go to significant expense to save the planet and will undoubtedly try to capitalise on that. And not always in an altruistic way.

Meanwhile, sustainability-oriented chef Cúán Green would love to see more opportunities to shop locally and seasonally. In his eyes, it’s an easy way to shorten the supply chain and reduce emissions. Looking to Europe as an example, he advocates for more markets in urban spaces. However, to make it a reality, he says we need subsidies. Right now, if Dublin people want to shop seasonal, local and direct from a farmer, they have Mac Nally’s in Temple Bar and the market in The Peoples Park in Dun Laoghaire. Both aren’t the easiest to get to. If we had supported and subsidised weekend markets across the city, many more people would be able to shop locally and seasonally. This may mean grieving for the convenience of all-year-round strawberries and broccoli but it’s a light compromise with big benefits. What’s more is, instead of branding them as sustainable, we could rally more people that “focus on flavour”. A local organic tomato grown seasonally tastes far better than any watery supermarket version.

This kind of reframing is as important as the proposed activities when pitching a more sustainable capital. People can’t imagine a fifty per cent reduction in energy, but everyone knows what a four-day week looks like”. So if we framed it as reducing your carbon emissions this week by cooking one seasonal locally sourced meal, then people would do it. They’re already doing it for hashtag meatless Monday.

In addition to how we think about climate change, making easy and accessible high impact changes are equally important. As a start, apartments need compost bins, even if it means getting them collected every day to prevent rodents. Likewise, we need every restaurant to be like King Sitric and have an overnight composter so that food waste isn’t actually wasted. If we can do both of these things and create a way to take this new compost and distribute it to the entire Irish farming community, it will, in turn, reduce the need for artificial fertilisers, which will mean we have cleaner water.

On a more complicated and macro-level, we must take the profit out of the things people need to survive. Energy is the clearest example of this. We are on the eve of the biggest energy crisis since world war two, and the energy companies have made €78 billion more profit in the first six months of this year.

This is a practice that should be illegal. Think of what would happen if this was public money. If that 78 billion was used to ensure every single home was not facing a housing crisis rent-sized bill at the end of October? Saoirse says, “another barrier is political cowardice, and a lot of it comes from the set up of our electoral system and democracy”. The current government simply isn’t brave enough to assert this kind of change on behalf of the people which is why we don’t see it.

Long term, it will be better for the Irish people if we address coastal erosion. It’s this fear of long-term planning because you need to keep your seat in government in the next few years. You don’t want to piss off the loud locals. But sometimes, you must piss off the louder people for the greater good. People don’t like to perceive that they are losing something so someone else can gain, but ultimately losing coastlines will not benefit anyone.

Saoirse is sure there will be a clash with these kinds of changes. She says, “there is a lot of fear, a lot of vested interests and power dynamics. And they will always resist change.” Because we, the people, are at breaking point, we will fight tooth and nail. But also, those who stand to lose their money and privilege because of this kind of change will fight tooth and nail for their gas and money. Any perceived loss is going to elicit anger.

Climate action is a complicated, terrifying and often jading path to pursue. So much of its success rides on having energy in the bank to take on what can feel like an insurmountable challenge. So on the difficult days, Saoirse suggests reading about about re-wilding. The things they have accomplished are really heartening. Saoirse said, “it’s magic how species come back, animals come back that they didn’t expect to come back, water is clean. I’ve found that it’s really fortifying to keep engaging in it.”

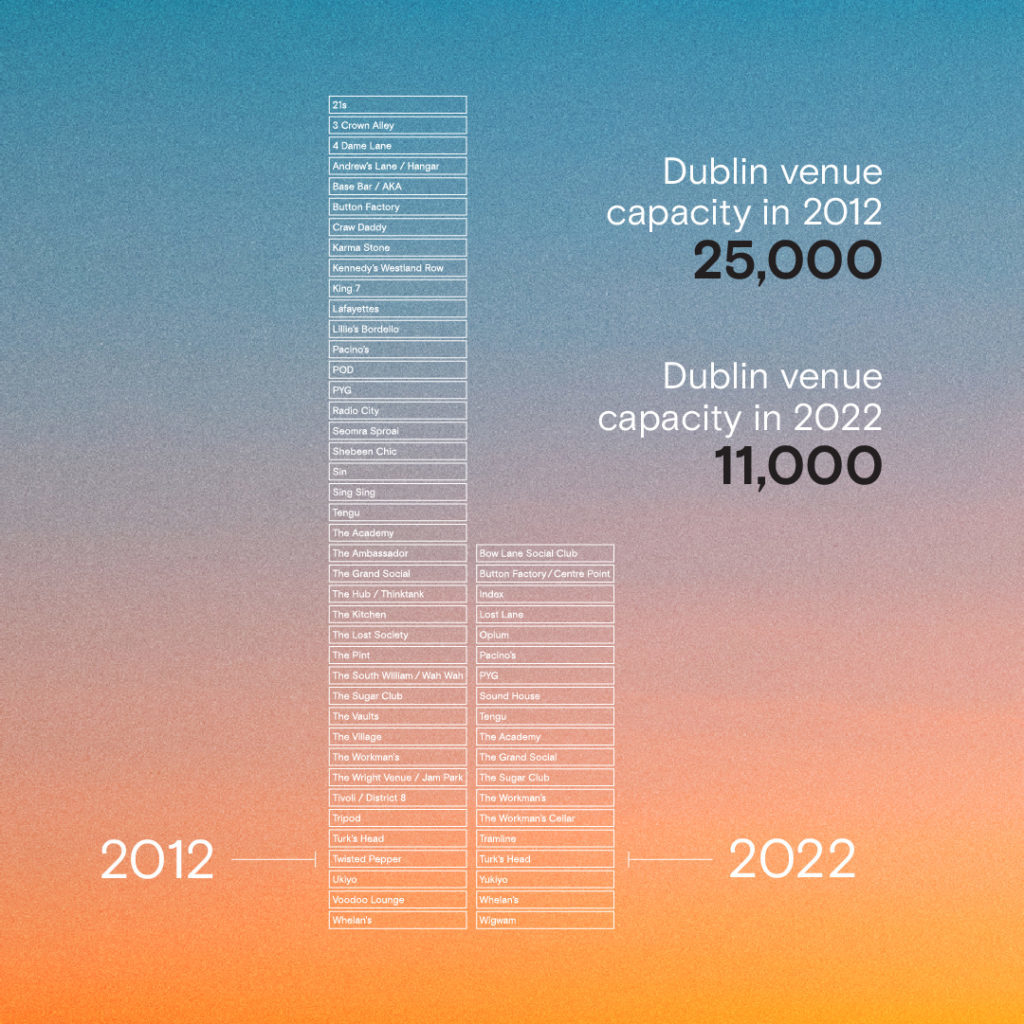

Culture

Culture is intangible. It lies somewhere in the intersection of art, people and place. It’s the soul of a city and what makes a city worth living in. There is a trifecta when it comes to making art. Time. Money. Space. If you have at least one of the three, you can foster creativity.

However, Dublin has been slowly and systematically removing each of these. Time is removed when young artists can’t afford to survive. Space is removed when buildings are only considered as a means for profit. Meanwhile, arts and culture funding as a percentage of GDP in Ireland is significantly lower than most European countries. So, how did we get here?

Developers and vulture funds intent on making money off property exploited a recessionary Dublin in need of investment and were allowed to buy vast tracts of land with little to no regulation to keep them in check.

Couple this hoarding with a political elite that only sees cultural assets through an economic lens and the result is a city that can’t meet the housing needs of its residents, let alone supply space for culture to thrive.

Currently, the supply of space is low and fees are high. Only multinationals can afford the extortionate prices. Often, new developments are required to include a cultural space in order to be granted planning permission. However, what we are seeing time and time again is that, for a variety of reasons, these cultural spaces within developments often go unfinished and almost never reach their potential as promised within the planning applications.

Subsequently, these mechanisms have recast our city as a conglomeration of private office buildings, corporate chains, and hotels.

The problem is, not only are cultural spaces closing, but they aren’t being replaced. There’s been a total of zero new music venues built in Dublin since 2010. Ireland does provide protection for buildings of “architectural, historical, archaeological, artistic, cultural, scientific, social or technical” significance, but rarely includes modern institutions in this category. Meanwhile, Berlin recently changed the legal status of certain nightclubs to cultural institutions, providing Ireland with a blueprint to preserve club culture. The move consisted in tax breaks and permissions to open in more parts of the city. This simple, effective change could come at a relatively small cost given its impact.

Likewise, introducing a “night mayor” would ensure there is an elected official whose job it is to protect night-time cultural spaces. London and San Francisco have one and it means there is someone bringing expertise to the table, advocating for culture and protecting our interests in rooms where activists are often shut out.

Additionally, a pragmatic move –given the effects of the pandemic– would be to turn unused office space over to culture creators. In this age of hot desking, hybrid weeks, and working from home, space is being reevaluated.

In Belfast recently, Digital technology company Kainos leased its Bankmore Square site to a pop-up market enterprise. Proposals were submitted, selected and despite a dispute, it happened in good time. Incentivising this in the same way tech companies are with massive tax breaks would make this turn around happen fast and efficiently.

The pandemic also introduced grant schemes, where the government opened up a new funding avenue for “commercial businesses operating from a premises in the arts, music and entertainment sector.” While the current scheme doesn’t cover the “purchase of lands or buildings”, Robbie asserts long-term investment in cultural spaces in the form of a capital grant scheme is essential to creating “incubator spaces” where artists are safe to experiment and grow their practice. Investing in space saves money long term. If culture makers can own these spaces, rent is slowly eliminated from annual budgets.

The plan with the Fatima Regeneration didn’t pan out when left up to the market. This plan was required to have a cultural space in order to be approved. But that, along with other promised amenities, never arrived and was ultimately forgotten about. As we build and develop social housing policy, we should make cultural spaces part of its planning, execution and evaluation. What’s promised needs to be what’s delivered.

Funding is the obvious solution to the current precarity. For the critics that argue that the changes cost too much money, we are one of the lowest spenders on culture in the developed world, according to this 2020 survey.

While it can sound like dead money, the UK has shown facilitating the arts is an investment that reaps rewards. Bodies like Arts Council England state that for every £1 invested, the nation benefits by £4 of rewards. If we valued our arts and culture similarly, given how similar our cultures have been historically, we could reap the same.

If you look at London, many flock to it for its arts across all avenues. If we invested a similar proportion of our national budget in culture over the next few years, we could also create this kind of world-class work. The tricky bit is that the path from investment to profit is rarely straightforward. It’s complex and fuzzy; we’re dealing with creative processes and human emotion, which can be infuriating for people who want clear, simple ways to measure profit margins.

BBC is one of the UK’s most prominent arts bodies, with several orchestras, a film investment arm, and many industry courses available to train and invest in the community. RTE is demonstratively not like this, though it should aspire to be. If we can make RTE less about bigwig personalities and pivot to investing in artist development programmes a significant impact would be felt quickly. This would mean a reshuffle of RTE’s objectives and maybe staff, so it’s more complex than just funding but if our national broadcaster better represented the people, it would not only make arts better but likely heal trust in the media company itself.

Annie points to the Universal Basic Income for Artists as a dream en route to coming true. This incentive has the potential to remove intrinsic poverty from cultural jobs. What it needs, however, is a living wage. The three hundred and fifty euro trial being rolled out at the moment chronically underestimates rent as an artist’s expense in the current rental market. This should be adapted to reflect that.

Every part of this plan is advocating for its own increase in funding. It seems impossible that a government can spend so broadly to make a population content. But it is possible. When we look at Nordic countries, they do it. We as a nation require this kind of investment in our country.

For details on how to submit suggestions to Dublin City Council’s Development Plan click here.