How Hennessy became rap’s favourite drink

Words: Caitriona Devery

Artwork: Cian Ryan

Hennessy is a drink with an unusual pedigree. The spirit is name-dropped in over a thousand songs, most of them hip hop. It enjoys an affection and a cultural currency that most brands only dream about. I remember being bemused to hear it dropped into rap tracks in the late 90s. It puzzled me how the brown bottle could be a role model for rappers as well as having pride of place in my parents’ drinks cabinet. That’s the curious thing about Hennessy. It’s a shapeshifter of a spirit, a drink that your granny might enjoy as much as 2Pac did, which is key to its polysemic appeal.

Brandy is the general name for a distilled spirit made from fruit, generally grapes but sometimes apples or pears. Hennessy is a cognac, which means a type of grape-fuelled brandy from the Cognac region in South-West France. Cognac is to brandy what Champagne is to sparkling wine, in that to be called cognac the brandy has to be made in the Cognac region to controlled standards. Hennessy is a very established cognac brand, accounting for around roughly half of global cognac sales. It’s hugely popular in Ireland. If you ask for a brandy in most Irish pubs, you’ll get a Hennessy.

Straight, Hennessy’s flavour profile is full of aromatic, subtle spice, orange and sweetness with a dry backbone. It’s fiery and no messing but also has a delicacy to it. We’ll get into how people drink it later, but first some history. Distillation is an ancient technique but wine distillation accelerated during the age of cross-Atlantic voyages. In the sixteenth century, Dutch merchants used a proto-distillation process to concentrate their wine to make it more robust and to reduce volume-based tax costs. It was stored in oak barrels which mellowed the flavour. They realised that this new product tasted pretty delish. The Dutch name for this distilled wine was brandewijn or burnt wine, which leads us etymologically to brandy. Rum and brandy offered comfort for sailors as well as being a profitable commodity to trade across the Atlantic.

Cognac, then, is a brandy made from dry and acidic white wine mostly from the ugni blanc grape variety, which is left to ferment with wild yeasts, then twice distilled in copper pot stills. The resulting 70% ‘eau de vie’ (the French for uisce beatha) is then aged in oak casks over years, taking the alcohol content down to a more manageable 40%. The final stage is the blending, a skilled craft which ensures consistency of flavour. Hennessy as a large-scale producer blends eaux de vie from multiple vineyards. They work with over a thousand winegrowers.

So, made from wine, has to come from Cognac, so it’s definitely a very French drink. Which is weird, because I grew up assuming Hennessy was Irish, given the name and its omnipresence in the parental alcohol stash we attempted to secretly fleece as teenagers. And it is, in a way. The first Hennessy distillery was established in Cognac by Richard Hennessy in 1765.

Richard was born in the village of Killavullen in Cork and was sufficiently bummed out by the penal laws to flee Ireland to join the French army aged nineteen, in the tradition of the flight of Irish young men called the Wild Geese. After time in the army, Richard set up a cognac business. The business survived the French revolution and his son James accelerated the business into other markets. By the 1800s Hennessy was trading via London and New York and doing very well.

From this improbable start fuelled by religious conflict and a young lad from Cork heading off to join the French army, Hennessy currently sell around fifty million bottles a year, around 40% of the world’s cognac. One of the largest markets is the US. Within this, African American consumers play a large part in its popularity. Cognac and Hennessy in particular is constantly referenced in hip hop. These days the brand is owned by Moët Hennessy, which is in turn owned by Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy and Diageo. So, it’s a big player.

Cognac bottles have different tags with letters indicating the category. The most recognisable bottle in Ireland is VS, which stands for Very Special but there’s also XO, Extra Old and more. There are other cognac brands of course; Courvoisier, Martell, and Rémy Martin as well as boutique and single vineyard brands, but Hennessy is particularly interesting in terms of how it came to be such so culturally refenced in hip hop.

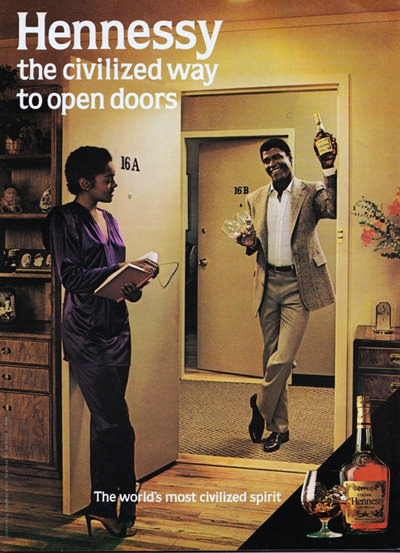

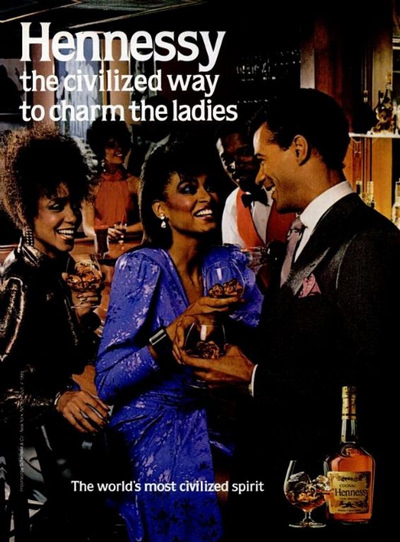

There are many layers to the story of hip hop and Black cultural affection for cognac in the US. One story goes that Black soldiers serving in the army brought home a taste for cognac after being stationed in France and getting it in their rations. Perhaps this French spirit appealed more than the brasher whiskeys of the day which had Southern and Confederacy associations, as I read in a 2013 Slate article. During the post war period of consumer expansion in America, Hennessy actively pursued this new market by placing ads in prominent Black magazines such as Jet and Ebony. They worked with Black actors in their ads depicting aspirational African American lifestyles that was not portrayed in most advertising at the time.

Hennessy became a familiar, trusted brand that laid the groundwork for the late pop cultural ubiquity. The company employed a Black Vice President, an Olympian athlete named Herb Douglas, at a time when senior African American appointments were rare. Sales to this day provide strong evidence of its enduring popularity with African American consumers.

There may have been other, deeper historical forces at play in terms of how politics, culture and consumer desire align. Scholar Paul Gilroy wrote about the emergence of a distinct Black Atlantic culture that emerged from the brutality of slavery and forced migration and makes the case that this transatlantic culture played a huge role in the emergence of modernism as a cultural form. This Black cultural movement including poetry, art and music such as jazz, came to a head in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s. The huge popularity of Harlem figures like Josephine Baker, Langston Hughes and Duke Ellington in post-war Paris may have imbued cognac with a certain charm for Black consumers. In the 70s and 80s, hip hop came on stage as a powerful cultural force and cognac came along for the ride.

By this stage, cognac was still popular in the US but was associated with older drinkers and not very visible. But something curious started to happen. In the late 1990s as hip hop began to truly go global via MTV, cognac and Hennessy in particular started to be referenced by rappers. It was dropped into tracks as a reference point for old-world luxury, enjoying the finer things in life and sharing a good time.

There are over a thousand songs that mention Henny, sometimes paired with a smoke or two. I didn’t listen to the full thousand, but I did get massively earwormed by ‘Hennessy’ by 2Pac and Obie Trice. With its zany French accordion riff and a looping laughing chorus, it is an ode to the spirit’s status as a comfortingly familiar and much-loved drink, putting the brand right in there as star of the show.

In the words of 2Pac,

They wanna know who’s my role model, it’s in a brown bottle

(You know our motherfuckin motto) Hennessy

It’s often referenced in the context of heavy-duty relaxation. For instance, Snoop gives it a shout out in ‘Hennessy n Buddah’

I got this henn in my cup

And this Buddah got me stuck

I’m just trying to compose myself, compose myself

Even recently it popped up in Cardi B’s recent WAP (my favourite cognac fact is that Cardi has a sister called Hennessy).

Look, I need a hard hitter, I need a deep stroker

I need a Henny drinker, I need a weed smoker

Not a garden snake, I need a king cobra

It goes on and on. Hennessy is key to the cultural scenography of hip hop from the 90s to this present day. It acts as a kind of social lubricant, aspirational but enjoyed by Black consumers on their own terms, a potent 250-year old French spirit absorbed and assimilated as a shared cultural reference point via hip hop. Both Hennessy and hip hop share a globalised history of production, consumption, adaptation and reinvention.

The company has shrewdly embraced the nature of its popularity, working with Erykah Badu and Nas on its 2012 Wild Rabbit ad campaign. Nas has remained as a long-time brand ambassador and stars in a recent ad ‘Dear Destiny’ where he reads a letter to his daughter Destiny celebrating Black excellence and the entrepreneurial spirit of Black communities. Unlike Cristal, who came across as snooty about their fans in hip hop, Hennessy has actively worked with rappers and Black musicians to build the brand beyond this initial affection.

Hip hop is an artform full of subversion and nods, sometimes tongue in cheek, always knowing. I bumped into rapper Mango on Fade Street when I was adding the final touches to this article. I asked him what he made of Hennessy. He said he always thought of Hennessy as something his granny drank. After she passed away, he himself realised its appeal. This reinvention of a link to the past is what he thinks appeals to Irish hip hop in the same way as it does to American hip hop. It goes down with Snoop as well as grannies, much like Just Eat. Mango gives Hennessy a shout out in ‘Rapih’

Guess who’s back

With Hennessy bars just like 2Pac

Dressed fresh, lemme get 2 snaps

How has Hennessy consumption changed in Ireland over the years? Similar to the US, it was once seen here as an older person’s drink and had that traditional association. But that has changed. Barman Lorcan Lynch who has worked in Whelan’s, Grogan’s and Anseo told me that in the 90s people used to drink it with port as a hangover cure, or to supercharge a Bailey’s. A friend of mine confessed a sad tale of a Hennessy and Bailey’s curdling incident that ended in disaster. In the 80s, Lorcan claims brandy and babycham was popular [Maybe in Dublin, that sounds very cosmopolitan]. In recent years, he has seen younger people drinking Hennessy with ginger or even Red Bull.

It’s hard to know what drives these changes. Whelan’s, Grogan’s or Anseo are not necessarily hip hop haunts. Nonetheless Irish consumption patterns have followed a similar trajectory to the US. Irish Moët Hennessy brand ambassador Paul Tuohy (@paul2e) confirmed my sense of Hennessy having multiple identities, from the ‘revered spirit’ taken neat to its central role in the history of cocktails. Its illustrious past includes starring roles in drinks like the classic Sidecar with orange liqueur and lemon juice or the creamy, dreamy Brandy Alexander.

Ginger ale is a classic mixer for Hennessy and cognac and soda is one of the first drinks ordered in the James Bond books. It pops up everywhere Quentin Tarantino films to, of course, hip hop. Paul sees the consumption of Hennessy evolving in Ireland. It was often taken straight but drinkers are starting to explore new mixers and cocktails, inspired by inventive bartenders.

Hennessy ran a global campaign last year to support the hospitality industry through Covid, called Hennessy My Way. Five hundred bartenders from around the world were invited to share thirty-second videos showcasing their creativity via Hennessy cocktail creations. Fifty of these were from Ireland, an indication of its popularity here. Many competitors opted for a reinvention of classic drinks like sours, sodas with handmade syrups, milk punches, and highballs. I cheekily asked if anyone went for a brandy and Baileys? Paul told me that Twelve hotel bar manager Simon King (@galwaytails) came up with ‘The Da’s Cocktail’, mixing Hennessy with his own cream liquor made with smoky Ardbeg whiskey and dandelion, with a dash of chocolate bitters.

I also liked the sound of epic bar star Gill Boyle’s (@gillybean_x_x_) invention, ‘Flamboyant Rouge’, which paired Hennessy Privilege with both cynar and chocolate bitters, and dark plantain syrup. With the My Way campaign Paul says they were trying to communicate that there’s no right way or wrong way to drink Hennessy. He told me Hennessy’s Irish roots are very important to the brand’s global identity. Apparently, there was a pub in Cork where regulars wouldn’t ask for a Hennessy or a brandy but for a Killavullen, which is of course where founder Richard Hennessy is from. A reminder of how the traces of history linger in what we consume, from Cork to New York, whether musically or in our glasses.