Robert Glasper on the many rooms of Black American music

Words: Dylan Murphy

District and Jameson Black Barrel share the same affinity for cutting edge music culture and few artists represent the intersectionality of forward-facing genres better than Robert Glasper. As part of the Jameson Black Barrel Smooth Series, the award-winning pianist and artist spoke to Dylan Murphy about breaking the mould, challenging traditional perceptions of jazz and how journeys to the strip clubs of Detroit with J Dilla informed his approach. Interspersed with the interview is a selection of Glasper’s many projects illustrating his prolific and versatile influence on hip hop culture.

Robert Glasper grew up playing the piano at church, but he’ll quickly tell you he’s not a church musician. The four-time GRAMMY-winning pianist hates being pigeonholed and has pretty much made it his mission statement since day one to blend genres and avoid neat categorization.

It’s an approach that’s stuck with him since his days playing Kirk Franklin’s mix of calypso, gospel and RnB in his local gospel hall where his mum was musical director.

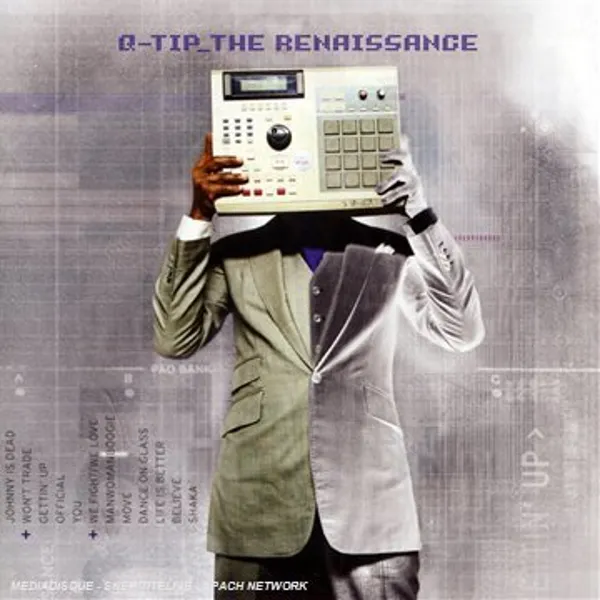

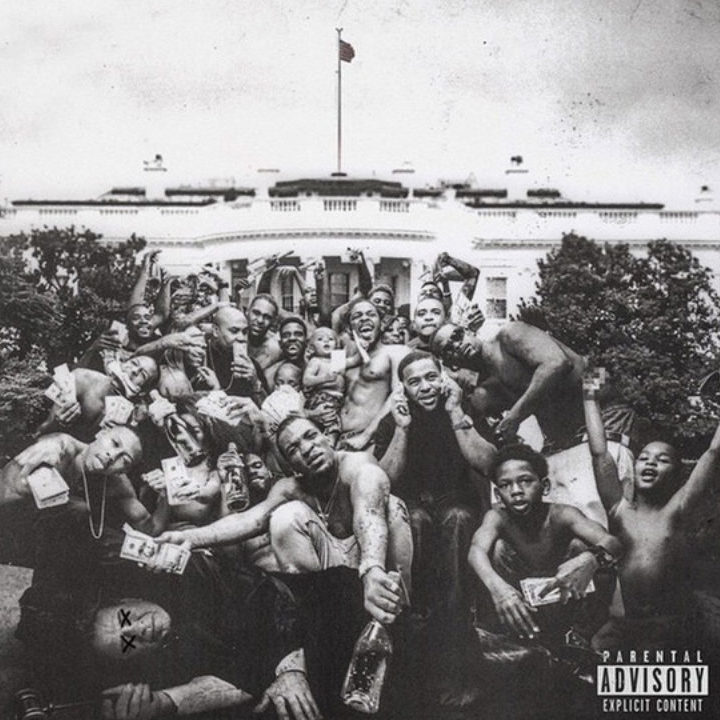

It’s resulted in a catalogue that’s varied, and if you are a fan of Hip Hop, Jazz or RnB its influence is inescapable. Even if you are unfortunate enough to be unfamiliar with his solo work, you’ve probably heard his approach across 9 of the tracks on Kendrick Lamar’s 2013 Jazz-funk hip hop opus To Pimp A Butterfly. It’s a seminal record that saw major players like Snoop Dogg, Terrace Martin, Thundercat, Rapsody and George Clinton all contribute. Yet no other act featured as frequently as Glasper.

If that’s still not doing it for you, another good insight to Glasper is his long and winding Wikipedia page, but even that struggles to capture his total contributions let alone his wider impact across music.

Having been granted exclusive access to Blue Note Records archives to rework tracks from Miles Davis and his first three records earning critical acclaim across the Jazz world he’s become an important thread in the genre’s fabric.

Meanwhile, collaborations with pioneers like Talib Kwali, Erykah Badu, Common and The Roots during their most influential years and work with the new school of innovators like Denzel Curry, SiR, and Kaytranada maintains a unique kind of intergenerational respect.

Additionally, it’s his penchant for crossing established borders that resulted in his Black Radio LP becoming the first album in history to debut in the top 10 of 4 different genre charts simultaneously and led him to score Emmy-winning documentaries

While he explains a zoom call from his Los Angeles studio that the church setting was an essential part of his journey to becoming more versatile, he notes it often paradoxically boxes other musicians in.

“It [Church] definitely informed me and most musicians I know. The problem with it is, some musicians get stuck in church and any style of music they play sounds like church – they don’t know how to differentiate it”.

“It’s one thing to be influenced by gospel – I’m influenced by gospel, but I’m also influenced by RnB, hip hop and Jazz. Everything I play doesn’t sound like gospel, it doesn’t sound like a gospel cat trying to play Jazz” he tells me from the cosy room that is densely populated with instruments and illuminated by the purple light that lines the walls.

In the mansion of Black American music, Glasper has had extended stays in nearly every room. During that time, he grew tired of the jazz elitist’s “secret club” mentality that closes the door to anyone that doesn’t subscribe to their rigid dress code and tight rule book. So instead, Robert has made a point throughout his career of doing the opposite. He’s the kind of guy that will crack a joke in the jazz club and greet you on the porch with a smile and in a pair of Timbs and a t-shirt.

That’s not to say it’s for everyone – it’s not, you really have to know your sh*t, but he wants you to know you can still rock jeans and play Jazz.

“Roy Hargrove showed me that. He came to my high school for a show and I’d never seen someone in jeans, sneakers and a baseball cap, you know, looking like me”, he says.

“Most people I’d saw were older with suits on, they weren’t talking cool they weren’t talking the language of my generation. From that point on I was like ‘hell yeah, I wanna do that’.”

“Most people I’d saw were older with suits on, they weren’t talking cool they weren’t talking the language of my generation. From that point on I was like ‘hell yeah, I wanna do that’.”

Robert Glasper

“You have certain people you play with that want you to conform. Obviously, when you are coming up and are young you got to play in other people’s bands, you gotta do what they ask you to do. I had to wear suits. I had to be a certain way with the music. You have to do that when you are coming up”.

“Once I was able to do my own thing…” he says rubbing his hands together in excitement, “I did my own thing. It’s important, that’s how you connect with kids”.

That’s where much of his magic lies. Not only has Robert Glasper mastered the delicate balancing act of marrying different genres on his own terms, but he’s learnt from and worked alongside the greats in those genres.

Recalling a time where he spent two weeks with J Dilla in Detroit, he explains it not only helped him hone his skills in the world of hip hop and RnB but reaffirmed the importance of music’s relationship with its physical home. It’s a notion he understood from his days in the gospel church and consolidated on a trip with Bilal to work with the legendary producer.

“We were at the end of our freshman year and Bilal got signed to Interscope Records, Jimmy Lovine signed him. The first producer they had him work with was J Dilla. So we flew to Detroit and we got to hang out with him for two weeks and that’s what we would do while we were trying to come up with something for Bilal” he explains.

“We would jam and then whatever he thought had the possibility of being something he would polish it up a little bit, Bilal wouldn’t even be finished with words and he would be humming stuff, some things had words and some didn’t. Dilla would take the instrumental of what we came up with, we would eat and then go to the club and he’d give the DJ a few of the instrumentals we did that day. The DJ would rock it and then we’d go to a strip club that night and he’d do the same thing at the strip club.”

“The strip club bro”, he says deadpan, repeating himself for emphasis before bursting into a characteristic chuckle. “He’d give the DJ the thing and he’d rock it. I’d never seen that in my life. Unmixed, unmastered, just ideas”

Dilla would take the instrumental of what we came up with, we would eat and then go to the club. The DJ would rock it and then we’d go to a strip club that night and he’d do the same thing at the strip club.

Robert Glasper

“My best friend Brian Michael Cox… he taught me that. When I saw him do it it made sense why Dilla did it. Brian has been in Atlanta for the last 20 years making music and they play all the hottest sh*t in the strip clubs. If you want to know the newest songs you go to the strip club or a club club“, he says differentiating between the pair.

“It’s one of two of those things. Dilla did both. We went to a club club and a strip club. That’s researching, that’s really a person researching. You aren’t turning on a radio station to hear the same five songs over and over. Strip clubs and club clubs play what they know people wanna hear, that makes people wanna stay, that makes people wanna drink, that makes people wanna turn up.”

“So with Brian, we’d do the same thing. We’d be in the studio making beats and he’d feel inspired and be like ‘let’s go’ and we hit like four or five strip clubs in a row and we’d only spend like 30 minutes in each one. He’ll just go to pick up the vibes and then we’d go back to the studio and start making beats. That’s what a lot of producers do, especially in Atlanta cause there’s a real strip club culture. Those clubs play what is new, what’s popping and if you are wanting to be inspired by that and you are looking at people’s reactions and then you are like ‘now I see’ and then you go back.”

While he was making inroads into the world of hip hop and RnB, Robert concedes if you asked Erykah Badu, Common or The Roots 20 years ago, they would’ve told you he was their “Jazz friend”. Not because they were pigeon-holing him, more because of their appreciation of his acumen as a trained pianist.

As an undergrad at New School for Jazz and Contemporary Music in New York, Robert quickly became a go-to collaborator for artists across the Soulquarians neo-soul collective. As he spent time with the talented acts and offered his skills he equally made a point to soak the knowledge of Questlove and his contemporaries. It resulted in him losing the “jazz” prefix and becoming synonymous with some of neo-soul’s defining moments, moments that were indebted to the spirit of collaboration.

“There was one time period where we were working on Bilal’s second record. We were in Electric Lady Studios in Manhattan, D’Angelo was on the bottom floor working on Voodoo, Erykah was working on the middle floor working on Mama’s Gun and we were on the top”.

“We locked that studio out for a month and a half and we were all running between each other sessions” he explains as his fingers march up and down the hypothetical stairs of the legendary studio.

It’s experiences like these coupled with frequent visits to the legendary Black Lilly jam sessions in Philadelphia where Glasper would play alongside The Roots that resulted in a more rounded education that meant he could chop and change styles at will.

Robert always had the intention to make music that meandered between the sounds he loved, but for him, it’s not as simple as changing the tempo and adding guest features. It’s about understanding the nuances and respecting the art form.

“I think it’s important that if you want to cross over you have to play with those people, the real people that do that music that you are trying to cross over to” he asserts.

“You trying to cross over to hip hop? You got to go play with some real hip hop motherf**kers, not other jazz musicians that love hip hop too. Not to learn – you need to learn with hip hop cats”.

For the nine-time GRAMMY nominee, he always wanted to be respected in the Jazz world before crossing over into other sounds. However, solidifying his reputation as a jazz pianist first wasn’t so much out of a desire to tick things off a to-do list in a predetermined order but in response in part to an unfortunate reality that sees Black artistry placed in reductive boxes. It’s something that came to a head when Tyler, The Creator called out the GRAMMY’s ‘Urban Music’ categories and it’s an issue that even the most talented acts still contend with.

“You know, I had a plan. I want to be respected in the Jazz world so I want to put out a few trio albums first, so I can solidify myself as a jazz pianist for real, so I can get that respect”, he explains.

“Then I’m going to move onto the other stuff that I’ve been dabbling with, I want to move onto the Black Radio vibe. Having guest singers, guest rappers, the neo-soul thing and mixing it with jazz. If I had done that too early I wouldn’t have the respect I have in the jazz world”.

I always say Black music is a big house and I like to go from room to room.

Robert Glasper

“Especially being an African American, unfortunately, even though it’s our music. If you are a black piano player they can’t wait to call you a hip hop piano player”.

“They pigeon-hole black people to certain things. If I show a glimpse of hip hop it’s like ‘oh that’s what you do. That’s what you really do! I knew it.’”

“I always say black music is a big house and I like to go from room to room. That’s my upbringing, I studied each genre of music that I play in a real way. I play with the masters of those genres, that is why I know how to play it so well.”

Speaking to District as part of the Jameson Black Barrel Smooth Series, Robert Glasper has highlighted that rather than compromising his status as a jazz pianist, his appetite for experimentation has elevated his career and simultaneously crushed outdated stereotypes. He isn’t a gospel cat trying to play jazz or a hip hop pianist dabbling in RnB. He’s a veteran that’s earned his stripes with the best in each genre’s spiritual home.

Whether that’s behind the decks in Atlanta’s strip clubs, opposite an MPC30 with the master of sampling, reviving Jimi Hendrix’s studio to birth neo-soul or simply playing piano on Sundays, the Houston native is opening the doors to jazz music’s exclusive club in a pair of jeans and a t-shirt.

Please drink Jameson Black Barrel responsibly.