Locked Out: How Ireland’s Voting Laws Silence Young Voices Abroad

Words: Izzy Copestake

Postal voting is not standard practice in Ireland. Instead, election day is marked by students rushing home to vote from their registered address, crises over childcare as schools close to accommodate polls, and negotiating a time to go and vote around the workday. But for the vast diaspora of Irish citizens living abroad, election day brings a choice between making an expensive last-minute flight home or simply not voting.

While there is an option to postal vote for some, the criteria for eligibility are highly specific, limited, and largely don’t apply to Irish voters living abroad. In fact, unless you’re a full-time member of the armed forces, an Irish diplomat, a citizen in prison, a member of the Garda Síochána, a student at an Irish college but living away from home, have an illness or disability, an anonymous elector (or part of their household), or unable to vote at your local polling station due to your occupation—you must vote in person. Even in these limited circumstances, the deadline to submit the necessary paperwork for this General Election was just two days after it was called—a near-impossible deadline to meet if you live internationally. What’s more, if you’ve lived outside Ireland for more than 18 months, you are no longer legally able to vote.

This exclusion contributes to a stark political continuity. The 2024 election saw Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael maintain power despite historically low vote shares, signalling little change from a century of center-right dominance. Turnout dropped to 59.71%, (down 3.19% from 2020), with disenfranchisement among young emigrants a key factor. Many of these young voters, who are statistically twice as likely to support left leaning parties like Sinn Féin or the Social Democrats than older voters, are effectively silenced by outdated voting laws—leaving Ireland’s political system increasingly out of touch with the electorate it should be serving.

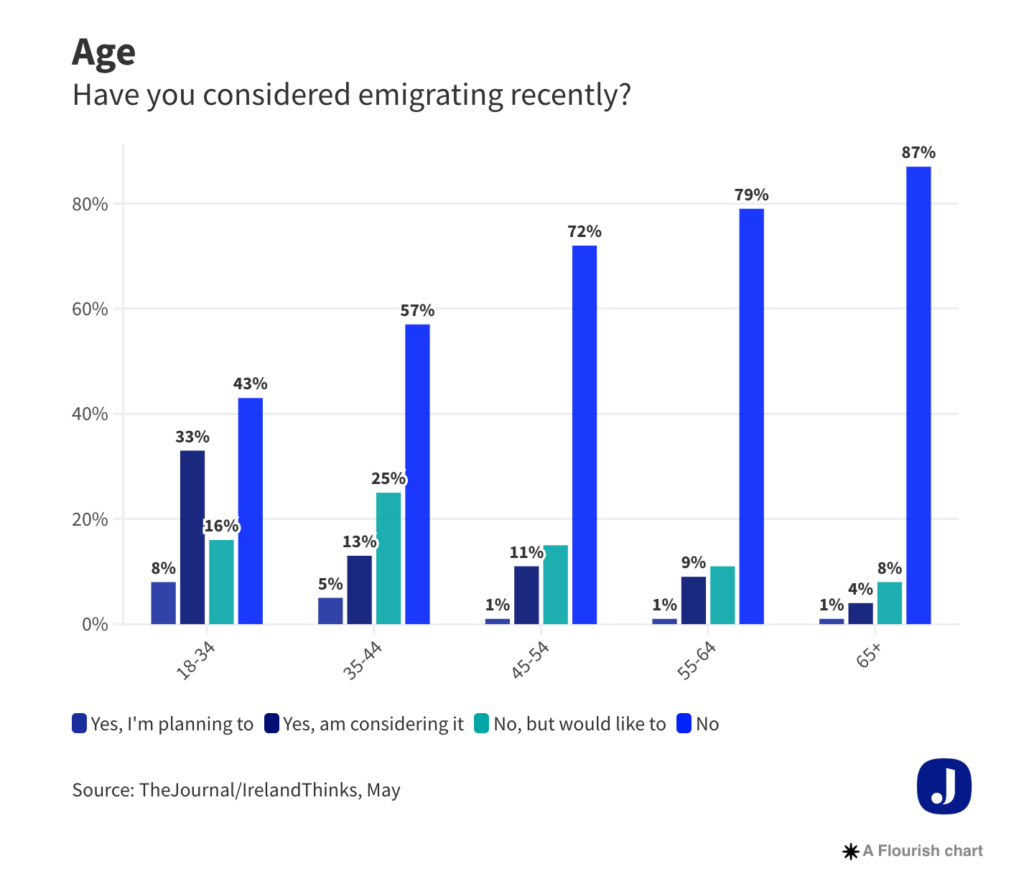

In 2017, the Department of Foreign Affairs estimated that the diaspora of Irish citizens living abroad (not including those in Northern Ireland) stood at approximately 1.5 million*. This number is growing, with at least one-third of 18–34-year-olds stating they are considering emigrating over fears around cost of living, housing, and opportunities. If government policies are pushing young people to emigrate, does preventing them from voting end up contributing to a negative cycle? The current trend certainly doesn’t look healthy for Ireland’s democracy and future.

24 year old Jen believes democratic system is contributing to this vicious cycle of continuity. Jen moved to Berlin after her studies for a sense of freedom she felt wasn’t being offered to her in Ireland, particularly as a woman of colour. Had she been at home, she’d have voted for Social Democrats, People Before Profit or the Greens, but returning home doesn’t look like an option for her any time soon with Fianna Fáil being the largest party in the Dail. “”So many people I know back home are still living with their parents, I was too before I moved. It’s not by choice; rents are outrageous, and moving out just isn’t realistic for most. Moving to Berlin gave me the freedom I couldn’t find in Ireland. The nightlife scene also needs better support, it’s so hard being a DJ in Dublin when venues are constantly shutting down.”

The situation is similar for 23 year old Katherine, who took an opportunity to work in Belgium after 23 years of living with her parents in Dublin and being unable to afford moving out. Similarly, Katherine would have voted for the Social Democrats or Greens. “With Fianna Fáil being the biggest party, I would be less inclined to come back to Ireland as I don’t think there will be a huge amount of changes, opportunities and possibilities for people in their 20s – 30s to live. I loved living in Dublin the last few years but with Fianna Fáil being in government, I am definitely not more likely to come back. “To keep people in Ireland, we obviously need to tackle the increase in rent prices, [and] the government definitely need to follow through with later opening hours.”

“With Fianna Fáil being the biggest party, I would be less inclined to come back to Ireland”

Advocacy groups and diaspora organisations have been campaigning for changes to Ireland’s voting laws for decades, such as the introduction of postal voting and longer eligibility periods for citizens abroad. The Electoral Commission Research Programme 2024-2026 described Ireland’s limited postal voting as “an area where Ireland seems to be an outlier in terms of international best practice.” Indeed, Germany, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Poland, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom all allow postal voting for any voter who needs it. In Ireland, progress has been slow and it’s impacting turnout and the government’s legitimacy. The government has cited logistical challenges, but critics argue that the real issue is political inertia. Extending voting rights could fundamentally reshape the Irish political landscape, potentially unseating the dominance of traditional powerhouses Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael.

The continued disenfranchisement of young Irish citizens abroad has serious implications for Ireland’s future. With record emigration driven by housing shortages, high living costs, and limited career prospects, the inability to vote amplifies the alienation felt by many young Irish people. As Ireland faces pressing challenges, from a worsening housing crisis to climate change, the exclusion of progressive voices risks stagnation in policymaking and a failure to meet the needs of the next generation. If Ireland wants to keep their next generation of voters in the country, it must reform its voting system to allow for progression. Without change, young emigrants will remain voiceless, more Irish people will leave in hopes of a better life, and the country’s future will be shaped without them—creating a home they may never return to.