Remembering Repeal

Words: Eva O’Beirne

Artwork: Paul Smith

Repeal is difficult to remember. It is exhausting and emotionally draining. There is so much that has been forgotten, and there is so much left to do.

Ireland hinges so much of its identity on storytelling, and the Repeal referendum afforded women a unique opportunity for them to tell their own stories, often at a personal cost.

Recent discourse around the National Maternity Hospital and the tug of war for expansion of current abortion legislation has left activists wondering if Repeal was merely a box-ticking exercise for politicians. Do Fine Gael really think that their promises made in 2018 would be forgotten?

In order to remember the build-up to the vote and everything that was sacrificed to convince the country to vote “Yes” on May 25, 2018, District has asked several campaigners from around the country how we should remember Repeal.

Here are their stories.

Róisín, North Donegal

Róisín was living in Galway in her third year of college when the referendum happened. She returned to her hometown on a tiny island off the coast of Donegal to campaign for two weeks straight before the vote.

“There was around eight of us total in the end,” she said. “Initially it was just me, my sister and her friend. But we recruited more along the way, driving around the entire of north-west Donegal.”

They spent two weeks straight, going from door to door, in the hope that the person who answered would grant them bodily autonomy before jumping back in the car and driving until it was too dark. Abortion wasn’t discussed in her village, not even amongst her family and Róisín suggests that the lack of dialogue is a reason why service provision across the country is so unstable.

However, she did emphasise that despite Donegal being the only county to vote no, people should remember the 48 per cent that did vote yes for Repeal. Remembering Donegal as a “No” county only prevents stories like hers from being told.

I think about all the generations before me that were on that island, everything that the women went through in that area, all alone. I realized, if they had access to proper health care, it could have been so different

Róisín, Donegal

Orlaigh, Monaghan

A similar weight rested on the shoulders of Orlaigh, who was still in secondary school and unable to vote in the referendum when it happened. Despite being in a non-denominational school, Orlaigh first became aware of abortion rights when a classmate was handing out pro-life leaflets after class.

Ultimately, it was Orlaigh and her friend Eoin who were the only people to campaign for “Yes” in her whole school, handing out badges and taking part in Twitter activism in their spare time. “I was 16, I couldn’t vote, I felt helpless, and so all I could do was campaign,” Orlaigh noted. “There were bullies and backlash but we kept going, as much as we could.”

Orlaigh and Eoin gradually pushed for more open debates in the school, challenging the misinformation that existed in the community. “People in my year kept asking me, why are you making such a fuss, why can’t you shut up? But I stuck with it, because it was our future, you know? It was something that would define the rest of our lives,” she explained.

“I changed my mum’s vote. I’m proud of that,” said Orlaigh. “But the negative feelings people had during Repeal haven’t gone away. Why we don’t have safe access zones, I don’t know. Why do we have a three day waiting period? Why don’t we have comprehensive sex education? I have so many questions and I wish someone could answer them.”

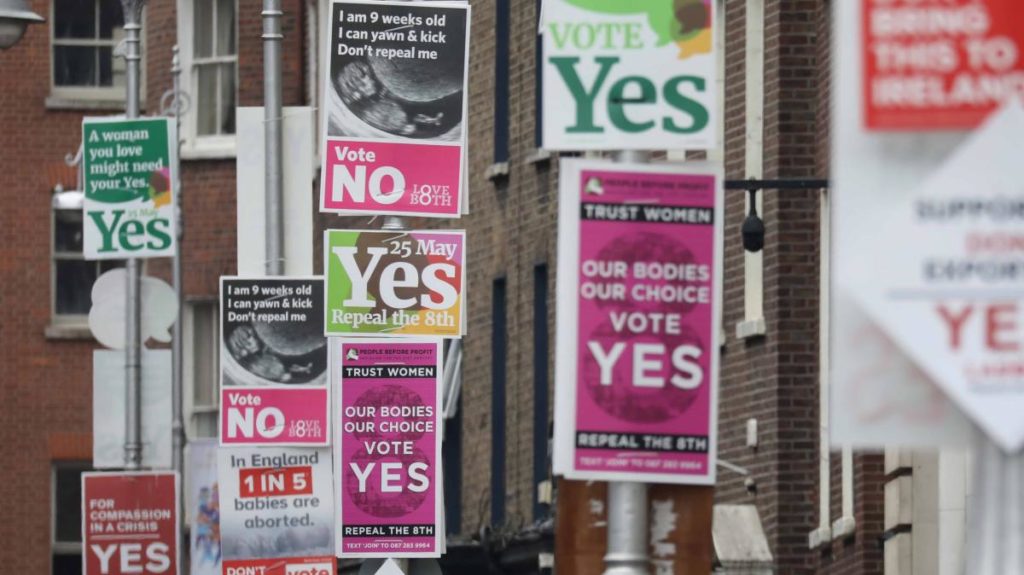

I really thought the “No” side could win because people would believe the lies they were spreading on the posters. No one challenged what they were saying.

Orlaigh, Monaghan

Susan McGrady, Galway East

Campaign materials were essential during the build-up to the referendum, and to activists like Susan McGrady, creating these materials was a full-time job.

Susan’s kitchen became a de facto HQ for Galway East for Choice and for around two and a half years before the referendum, Susan and fellow activists from rural Galway campaigned constantly, often staying overnight to make badges and ship them across Ireland and internationally.

“It started with a coffee morning,” she described. “A number of people who I already kind of knew came, so did from parents from my kid’s school.”

That coffee morning soon turned into an information stall, which turned into regular trips into Galway city centre. And from the very beginning, pro-life activists had been watching them. “I remember our first stall was awful,” said Susan. “We just had one person after another telling us that we should be ashamed of ourselves. But I got up the next day and went back to campaign again, on my own.”

While at the stall, an old man approached Susan. Expecting the worst, she braced herself for the same comments as the day before. To her surprise, he emptied his pockets, giving all his spare change to the cause. “It was around a euro, 1.70 maybe,” Susan smiled as she told the story. “But it was all the kindness I needed to keep going.”

When asked how people should remember campaigning for Repeal, Susan points to her tattoo, which is the very same design that used to be on the badges she made: “It was the solidarity, the girl gang in the black jumpers and that did the impossible. We did it. And we can do more.”

Some days you just had to go, take a break, have a cigarette, cry, come back out, smile and hand out more badges.

Susan McGrady

Anna Cosgrave, Dublin

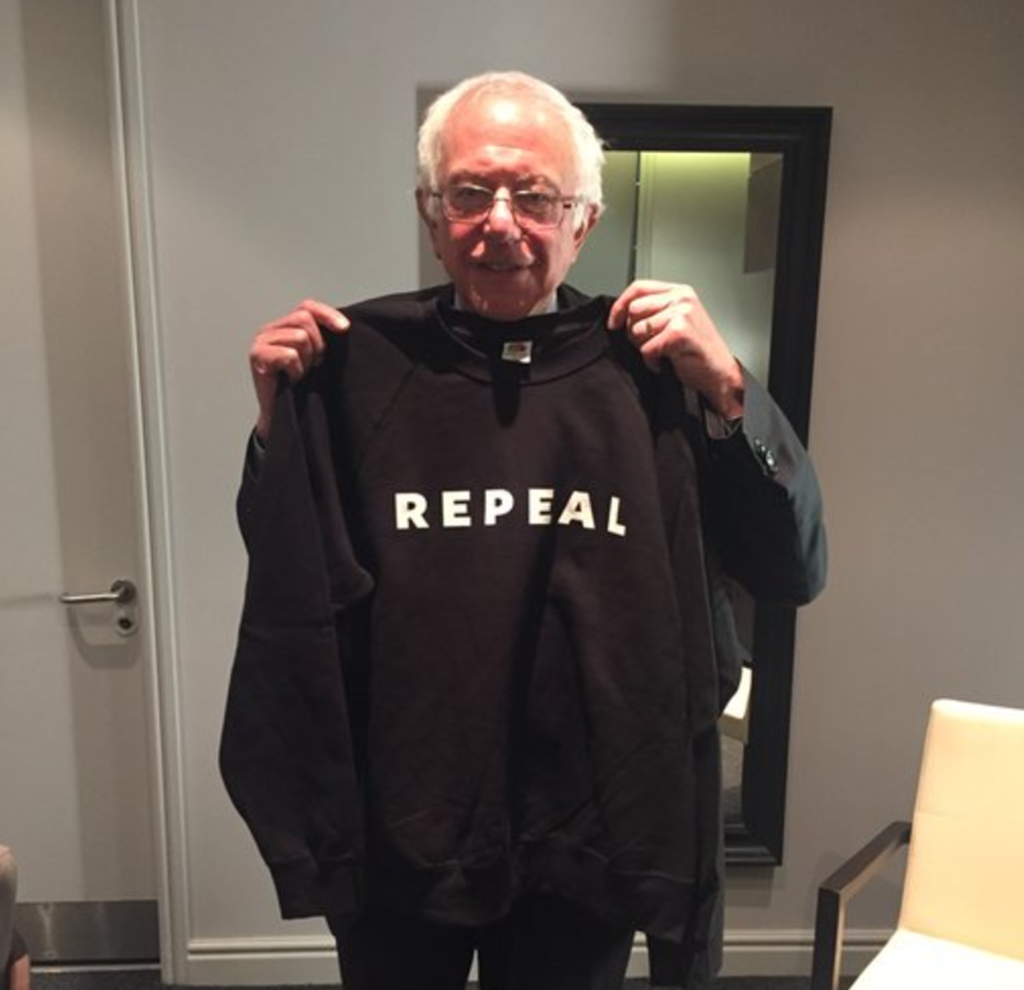

Like many, the death of Savita Halappanavar in October 2012 was a catalyst for Anna Cosgrave’s involvement in campaigning for abortion rights in Ireland. Inspired by a t-shirt Gloria Steinem wore, she launched her REPEAL design that was worn by the likes of Hozier, Bernie Sanders among others.

However, to Anna, Repeal shouldn’t be remembered by who wore a jumper but rather how the abortion laws Ireland received aren’t what was promised.

“There are still huge gaps and disparities in abortion provision in Ireland,” explained Anna. “We see working class, disabled people, rural communities and those living in direct provision impacted gravely. Our government is still forcing people to travel, for healthcare. Our legislation is failing. We need full decriminalisation of abortion and a thorough and appropriate expansion of services to remove barriers.”

“Ireland voted for choice, voted to trust the pregnant person and yet the legislation is not. The shocking origins of The 8th Amendment, it’s harrowing consequences and it’s realities are still hanging in Irish society today. The work is not yet done. Ireland’s conservatism towards reproductive healthcare has a long muddied legacy.”

The REPEAL jumper, alongside badges, created a space for Irish people to have conversations without speaking, to show solidarity without having to beg and plead for reproductive justice from strangers.

The REPEAL jumper became a sign of solidarity and symbolic of Irish people that were tired of hiding their stories, tired of not having a choice over their bodies. Anna fears that these stories could become common again if our legislation is not altered soon.

“I was at the march for the National Maternity Hospital on the weekend – that prospect is terrifying. So much work can be reversed by a conservative majority on any decision-making board, and we can see that from what’s happening internationally,” said Anna. “We can’t give up. Not now and not ever.”

Leo Varadkar called Repeal a “quiet revolution”. But to anyone campaigning, it wasn’t “quiet”, it was the loudest we’d ever been

Anna Cosgrave

Bethany Moore, Derry

Bethany, a member of Alliance for Choice Derry, sees Repeal as a vital part of her activism journey. For so long, the south appeared to be ahead of the north when it came to women’s rights but as it stands, Northern Ireland currently has more progressive abortion legislation than the Republic. With safe access zones and no waiting period, as well as later-term abortions available in certain cases, Bethany noted the juxtaposition between the two states but carefully highlighted that abortion access in the north is continuously under threat.

“In the run-up to Repeal, I got involved in campaigning through a solidarity group in Queens University Belfast. Repeal meant everything to us because it signalled that we could have rights too.”

Promises of “the north is next” were a disappointment to activists in Northern Ireland, who battled for another year to have the procedure decriminalised, and it wasn’t even by popular vote. Even with intervention from Westminster, abortion access in Northern Ireland is still limited in 2022, with women still travelling to England to access services as many doctors don’t recognise twelve weeks as the legal limit for all cases.

Bethany also pointed to the fact that Aontú got 12,000 first preference votes in the recent Stormont elections as a reason for anxiety amongst NI activists. “There’s more of us than there as of anti-choicers and I think they’re fighting a very nasty fight at the minute because they know they’ve lost,” Bethany explained. “But while our laws are progressive and inclusive, they’re nothing without the access to match, and that’s why we’re worried.”

Sorcha, Clare

Sorcha, originally from Clare, feels the same way about abortion access in the west of Ireland. During the Repeal campaign period, she was living in Dublin while attending college. For Sorcha, it was the Late Late Show debate on the topic that triggered her inspiration to campaign in her hometown.

“I was always very passionate about the topic and the campaign, and originally I did find the Together For Yes, the whole campaign, really overwhelming and I couldn’t find a way in. But then I saw the debate and decided to campaign at home,” Sorcha explained.

“It was the misinformation really, it was also the fact I felt the “No” side won because they were being louder than anyone else. And I was scared of people from home thinking the same way,” she said. “But I was delighted when I came home, because I was wrong. I started to believe that narrative of “oh Dublin is way ahead of everyone else”, you know?”

For young people like Sorcha, Repeal signalled that it was okay to leave Dublin and return home, that the rest of the country had caught up with more liberal attitudes to women’s healthcare. But with half of counties in Ireland having less than ten GPs that offer abortion care, the reality of a post-Repeal world isn’t good enough.

People are still travelling as not enough GPs have signed up, the issue with the God Squad outside hospitals and GP surgeries. Women in Direct Provision. Traveller women, women experiencing domestic violence I fear are still not cared for and of course poverty and young girls. Lots done, lots more to do. Consent still an issue in hospitals.

Former canvaser (2020) – Repealed by Camilla Fitzsimons

I remember it was a year after Repeal, and I was on a bus in Dublin wearing a denim jacket and I didn’t realise it had a Repeal badge still on it. I’m sitting at the back of the bus and I was getting up for my stop, but the woman facing me pointed at my badge and stood up too. And she hugged me and said thank you. It was nice to have what we went through acknowledged.

Sorcha, Clare

Fay White, National Women’s Council Ireland

Fay White, the Women’s Health Officer from the National Women’s Council of Ireland can’t emphasise the importance of the ongoing Repeal Review enough, as well as awareness of how little the current abortion legislation fulfils the promises made in 2018.

“Women in Ireland have always assumed a “carer” role,” Fay explains. “So when the pandemic came along, women’s healthcare was pushed down in priority. Women had to travel for abortions during the pandemic, they couldn’t access their regular GP appointments and so we won’t know the full extent the past two years has had on women in Ireland for a long time.”

The National Women’s Council see several elements of the current abortion legislation in Ireland as problematic, as well as the issue of abortion access.

Between the three day period to the criminalisation of abortions past twelve weeks in Ireland, Fay notes the many women that are currently left behind. “Women who need to take time off work, find childcare, women who have miscarriages past twelve weeks. Homeless women, women who are experiencing domestic violence, women in Direct Provision and women who can’t afford to travel four hours to the nearest doctor. We can’t forget these women.”

Only 1 in 10 GPs is offering abortion care and not all of them are able to take referrals through My Options, the HSE’s unplanned pregnancy support service for the general public

National Women’s Council

Three weeks before the May referendum, 31 Fianna Fáil Oireachtas members proudly posed for a photo calling for a no vote – an image that continues to haunt the party and activists alike.

While celebrating their 87th anniversary in 2020, Fine Gael listed “repealed the Eight Amendment giving women the right to choose” as one of their key achievements. But the women of Ireland didn’t choose to lease the new National Maternity Hospital from a religious group that has refused to give redress to victims of Magdalene laundries and Mother and Baby Homes.

There was a piece published in the Irish Examiner by Eoin O’Malley, detailing how activists would soon forget the debates around the National Maternity Hospital. For those in Government (and their supporters), it really would be convenient for activists to let go and move on from protesting about Church and State relations. It is too easy to imagine Micheál Martin and Stephen Donnelly shaking their heads and complaining about those pesky feminists in the Dáil bar.

But what Eoin, and those in Government, don’t realise is that the people of Ireland can’t afford to forget. As the tug of war of reproductive rights continues into the next decade, it is absolutely essential that the Repeal Review delivers on the promises made back in 2018. We’ve come too far to forget, too far to experience substandard reproductive care.

We must remember Repeal, otherwise, we wouldn’t remember all the #UnfinishedBusiness that’s left to do.

Elsewhere on District: Why things have changed but it still ain’t different for Tebi Rex