Somewhere to live, but at what cost?

Words: Izzy Copestake

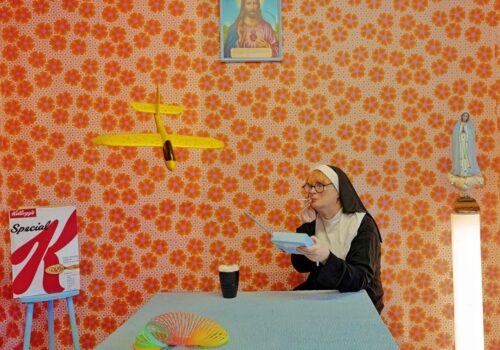

‘Generation Rent’ no longer applies to Ireland’s under-30s. This is ‘Generation (Pa)rent’, but what are the psychological impacts of living in your childhood home long into adulthood? Infantilisation from older generations, shame and a lack of freedom: but in this economy, young people should not be the ones shouldering the blame.

Young people in Ireland have often been tagged with the term ‘Generation Rent’. The phrase was coined back in 2011 by Halifax Building Society to describe the grim prospects home ownership in the UK. Just last year, Irish homelessness charity ‘Threshold’ released a report titled: ‘WE ARE GENERATION RENT’ – suggesting Ireland has the same issue 13 years later. But according the Threshold, ‘Generation Rent’ no longer applies to just Irish people in their 20s, but people in their 30s, 40s, and even retirement age. 68% of 25-29 year olds in Ireland live with their parents, a concerning contrast to the EU average of 42%. So, can we even describe 20-somethings in Ireland as ‘Generation Rent’ anymore? The average monthly rent in Dublin is $2,400 and the monthly living wage is $2,368 (before taxes). Renting is simply not an option for young people in Ireland, many have emigrated – but for those who stay, moving back in with family is the only viable option.

It’s understandable. Doom scrolling through the mouldy and impossibly expensive box-rooms on Daft.ie can come with a dreadful realisation: I cannot pay rent and survive in this market. So, returning to the childhood bedroom can bring with it a level of financial security, but not without an emotional cost.

“Delayed independence may lead to a diminished sense of self,”

Psychologist and Relationship expert Mairéad Molloy

Psychologist and Relationship expert Mairéad Molloy says that living with your parents after a certain age can have serious psychological effects, even if your relationship is good. There’s a reason people begin to feel like a teenager again after staying at home for Christmas, but what happens when this cohabitation becomes necessary for longer periods of time. “Delayed independence may lead to a diminished sense of self,” Molloy tells me, citing things such as diminished responsibility and budgeting as key players in this. However, the real problem is obvious: privacy.

“Young adults living with parents in my view will have poorer mental health than those living independently”

Psychologist and Relationship expert Mairéad Molloy

According to Molloy, a lack of privacy and independence has a direct impact on young people’s mental health. “Young adults living with parents in my view will have poorer mental health than those living independently, unless they have exceptional levels of privacy.” Molloy stresses that while lack of affordable or available housing is not young people’s fault, there is a cultural element at play in Ireland where dependence on the family home past a certain age can make young people feel like a failure.

Last week, YouTuber Keelin Moncrieff appeared on RTE’s Prime Time and called for the government to take responsibility for the country’s lack of housing. “I think it’s a disgrace that people are told that they can’t get a house because they’re not working hard enough or not making enough money. That’s not true. That is a lie we are being told. ” Moncrieff said she made a substantial salary for someone her age, but cannot afford to live close to her family due to rising costs. Shame and unfair judgement a all contribute to the mental strain.

This mental burden is perhaps most obvious for young people who have had an opportunity to live independently for a period of time, say during college, but are later forced back into the family home. 23 year old Katie* from Northern Ireland had lived away from home in Dublin for a number of years, before returning to her family home after college. “It’s the regression that occurs,” Katie tells District. “It’s reverting back to the previous self or state you were in before leaving. I think this happens on two levels, partly because your parents haven’t seen you emotionally and socially since you’ve been away, and partly because you know a practiced set of behaviour in the home space that you will just automatically revert back to being there.” Katie tells me how this regression particularly harmful for her sense of self.

Theres a scientific reason why we feel like a teenager again when we visit home. “Some interactions with family members and others from the past can reinforce past roles and dynamics,” says Molloy. “This can make us fall back into patterns of behaviour, often unintentionally. Going home can reconnect us with past interests, values, and aspects of life we have forgotten about.” Returning to your angsty-teenage self for a couple of days while visiting your parents over Christmas is one thing, but living at home for the foreseeable future is another.

“I’ve personally experienced many comments about me being a drain on my family, living off my parents”

Katie, 23, Northern Ireland

Identity is not the only thing under threat. Many young people who are forced into these situations frequently experience judgement and infantilisation from older generations. “I’ve personally experienced many comments about me being a drain on my family, living off my parents,” says Katie. “I think theres a real lack of understanding with the financial and social situation for young people at the minute.”

“My parents know everything about my life”

Grace, 22, Dublin

As depressing as the ‘generation rent’ stereotypes were for people in their 20s, at least having your own space comes with a level of freedom natural for an adult. For 22 year old Grace*, living at home means a sacrifice of the kind of rite of passages associated with youth. “My parents know everything about my life, which I feel shouldn’t really happen at my age. They know what time I come back from a night out at, because my mum always wakes up. They ask me why I was so late. I sometimes feel like I live a mid-50 year old’s life, because I come home from college, chat to my parents and watch First Dates or Room To Improve, which is a bit brain melting. I definitely don’t see my friends as much at all, I’m less likely to go out.”

The situation for some is bittersweet. Conor O’Brien, owner and creative director of Irish knitwear brand Conor O’Brien Studio, lives at home with his parents, 27 year old brother and 14 year old sister. “I feel a great sense of privilege that I’ve got a roof over my head free of charge, I don’t pay rent but I contribute in other ways to the household.” Conor says he has a great relationship with his family, but jokes that it’s a bit worrying that he’s living in a situation where things like cooking and budgeting aren’t issues, “I definitely feel a lot more anxiety around the prospect of basic survival instincts.”

“I’ve taken taken people home, they’ve slept over and I’ve almost been murdered by my parents,”

Conor O’Brien, 23, Dublin

Regardless of the safety net, dating as an adult living home, naturally, brings its own issues. “I’ve had two major blunders where I’ve taken taken people home, they’ve slept over and I’ve almost been murdered by my parents,” says Conor. “This is a driving factor in me wanting to move out.”

Living with parents comes with a cost: Relationships, personal growth, mental heath and identity are all under threat from the housing crisis. Blaming young people for the failures of the government only creates a culture of shame and embarrassment… which is, probably, the only way to make the situation worse.

*Names have been changed for privacy