What would a “right to housing” look like?

Words: Ellen Kenny

Art: Jan Walsh

Images: Unsplash

This month, the Government launched a public consultation on the “right to housing”. But what does a right to housing mean, and how can Ireland make it happen?

Houses. We all want one. We all deserve one. People have campaigned, protested and have even been arrested trying to find one. A roof over one’s head is one of the most basic human needs. But it is also causing some of the most contentious discussions and debates.

For years now, academics and activists have urged Irish people to reconsider the way they view a house. To view it as a natural right, rather than a commodity reserved only for those on high salaries. Now, the deepening crisis has spurred the conversations further.

Ireland is in a crisis, or as President Higgins more accurately said, a disaster. There are over 10,000 homeless people in Ireland, with more than half of them in Dublin alone. Approximately one in four Irish adults are affected by hidden homelessness. Counter-intuitively, there are 166,752 vacant homes in Ireland.

In 2021, 20,433 homes were built, but just 7,568 of those were actually bought by home buyers. Property developers have taken over the housing market, and the Government shows no indication of changing this.

The average house price is now almost ten per cent more expensive than last year. The average cost of rent for a full property in Dublin is now 2,200 euros per month.

The statistics keep building up, but the bottom line is that the current system is broken.

Given the seriousness of the situation, the Irish Government has started considering new options. The Housing Commission was set up this year to consider the features of a proper housing system and “introduce a good housing system in Ireland”.

At the start of July, the Housing Commission launched the Public Consultation on a Referendum on Housing. Lasting until September 2, the consultation was formed to figure out the logistics of implementing a right to housing in Ireland. And whether this is something Ireland should even do.

But what does a right to housing mean? Why do we need a referendum about it? And what would a constitutional right to housing actually change about Ireland?

Why do we need a referendum?

Irish people don’t get to make every decision on how the country is run. That job is left to elected politicians most of the time. However, the principles and values laid out in the constitution guarantee certain rights to the people of Ireland and can be amended by a referendum. So a referendum on a right to housing presents an opportunity for the people of Ireland to have agency on the issue.

If successful, the constitutional change would endure beyond the term of the current government and would exist above ideological differences and policy preferences as the common good dictating the lives of all Irish citizens across all time.

What would a right to housing look like in the constitution?

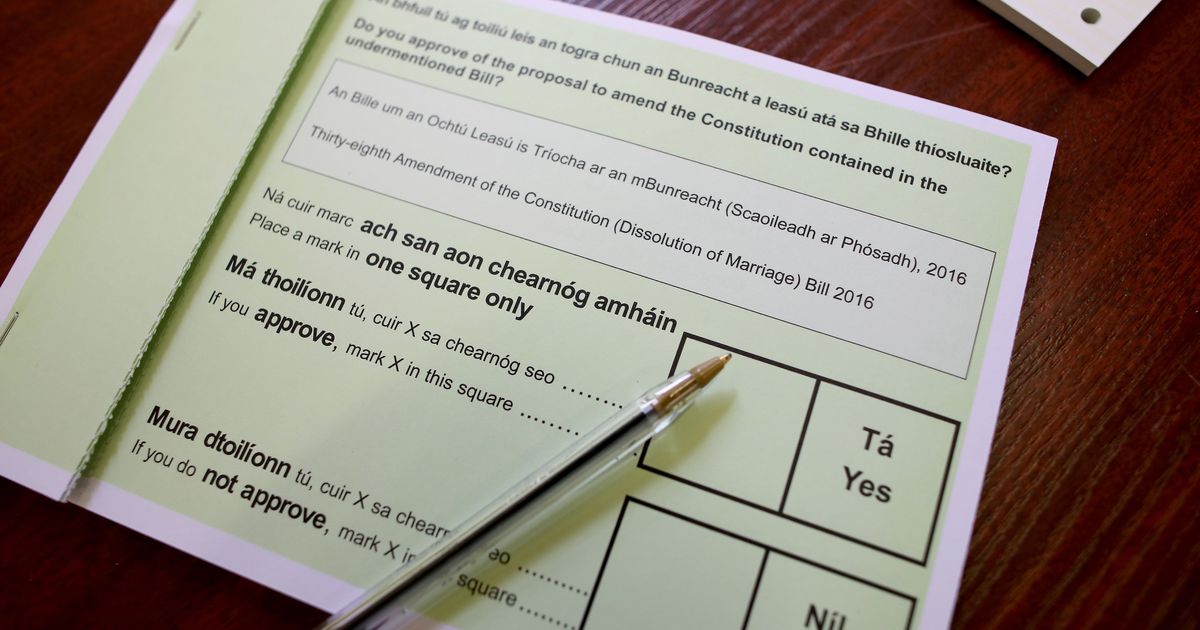

Of course, when you rock up to the polls for a referendum, your ballot just says “yes” or “no”. Even though it’s ultimately the choice of the Irish people, the majority of the work into a referendum occurs behind the scenes.

Before anyone can vote on whether to add a right to housing into the constitution, the exact wording must be decided upon by constitutional experts and politicians. And the language makes all the difference for the impact the right will have.

According to constitutional expert Professor David Kenny, there are many ways the right to housing could be worded in the constitution. “Depending on how far you want the constitutional protection to go, and what you want it to do.”

Professor Kenny suggested that Ireland might follow the lead from other countries that have implemented a right to housing, such as South Africa. The right to housing in Búnreacht na hÉireann, then, would read:

Article 43A- HOUSING

1. The State acknowledges that everyone in the State has the right to have access to appropriate, affordable and secure housing.

2. The State shall take reasonable legislative and other measures, within its available resources, to achieve the progressive realisation of this right, in accordance with the common good and the principles of social justice.

3. No person may be evicted from their home, or have their home demolished, without a court order made after considering all relevant circumstances. No legislation may permit arbitrary evictions.

Sounds pretty fun, doesn’t it? Professor Kenny reckons that the more direct wording, the better. People need to understand what they’re voting for, of course.

What would the government be required to do?

Right now, the Government hasn’t taken a very active approach to housing in Ireland. As Professor Rory Hearne, author of Housing Shock, put it, “at the moment the Government just hands over responsibility for the provision of housing to the private developers and investor funds – it’s all about the market. But the market has failed over and over and over to provide affordable homes.”

So, let’s say we go with Professor Kenny’s suggestion of how to word the right to housing. Hypothetically, it passes. What is the Government obliged to do now?

To put one question to bed, a right to housing would not mean everyone gets a free house. Despite what objections say, it wouldn’t mean you could stop paying rent and not get evicted. It wouldn’t mean that someone could break into your house and claim that they’re your new roommate under their constitutional right to a house.

According to Sinn Féín’s spokesperson for Housing Eoin Ó Broin TD, the constitutional right to housing simply “places the legal obligation on the State to take whatever action it feels necessary to get people homes.”

Right now, if the Government refused to let you marry your partner of the same-sex, or get an abortion, you can bring a lawsuit to the High Court of Ireland. Now imagine if you could do that if the Government was ignoring unfair evictions? Or if they were allowing too many homes to go vacant and too many people to remain homeless? Or they allowed too many vacant properties in your area?

“If the State was in breach of the right to housing, which was negatively affecting people, the people affected could take matters into their own hands and challenge the State in court, and the Court could decide if the State was breaching the Constitution.”

Ó Broin thinks that these lawsuits would be “few and far between”. But citizens having the ability to “take matters into their own hands if they feel they are being denied their rights” would likely prompt the Government to take a lot more action.

Ó Broin explained that whatever action the State takes to implement the right to housing “is a matter of the democratic process”. In other words, Fianna Fáil would implement the right to housing in a different way than Fine Gael. And they would obviously do it a different way than Sinn Féin.

But even if a constitutional right to housing creates less of a checklist and more of a nudge, that nudge would break down a lot of barriers.

Professor Hearne says, “I don’t see any other way of making systemic change in this country other than putting a clear right to housing in the Constitution that would make the Government and State, whatever Government is in place, obliged under the highest document and guiding principles in this country to ensure everyone has access to a home.”

“I don’t see any other way of making systemic change in this country other than putting a clear right to housing in the Constitution”

Professor Rory Hearne

How will landlords, tenants, and owners be affected by the right to housing?

Professor Hearne explains that the right to housing would need to go under section 43 of Búnreacht na hÉireann to balance the right to private property. The right to private property is what grants landlords and development companies the right to own multiple properties and rent them out to tenants.

The constitution also states that private property cannot conflict with “the common good”. But this right is what largely protects landlords from measures that would protect tenants such as rent freezes and stricter regulation of evictions.

Previous governments have refrained from implementing rent freezes or controlling the amount of property one person or company owns, in the name of private property rights. However, a constitutional right to housing would, in many cases, require these measures.

As Professor Hearne explains, “Currently policies such as extending the ban on evictions, removing the ability to evict a tenant on sale of a property, or putting some aspects of controls on rents are deemed not possible by the Government due to potential constitutional issues.”

“Putting in place a right to housing is about creating a housing system that is balanced, that works for people to provide a home.”

Professor Rory Hearne

Under a right to housing, however, the common good might prevail: “This right to housing should make it clear that such policies are possible, so the impact of it on landlords will be about strengthening tenants’ security of tenure and rights.”

“A right to housing will further strengthen home ownership, as it will copperfasten people’s right to their home,” Professor Hearne suggests, “Putting in place a right to housing is about creating a housing system that is balanced, that works for people to provide a home.”

“There will still be privately owned and provided housing and hopefully a significant increase in public housing. It should actually lead to an increase in affordable homeownership as our housing market becomes focused on providing homes, not investment assets, and it should lead to an increase in social housing, and in affordable rental housing.”

Landlords have previously highlighted their concerns over their rights being infringed on by the government this year. The current ‘eviction ban’ caused landlords to claim that they were being discriminated against. A first step to securing a right to housing, this eviction ban echoes previous actions taken to protect tenants during the pandemic and is in place until March 2023.

Focus Ireland has previously pointed out that the number of people in emergency accommodation in Ireland actually fell during the pandemic and that the total ban on evictions was “clearly a very significant factor, with strong evidence that the banning of ‘eviction-to-sell’ being the biggest factor” in preventing homelessness.

But when will this happen?

It’s still early days for the right to housing. The Public Consultation on the Right to Housing closed on September 2. (any updates on this) The results and analysis will decide whether Ireland needs to have a referendum. And then it’s a lot more discussions and debates in the Oireachtas before we ever get to the ballot.

Ó Broin suggested that the referendum might not even happen in the lifetime of this Government, as Fine Gael has come out against the right to housing in the past. However, Fianna Fáil is actually much more in favour of it, as are the Greens. And with the right to housing included in the current Programme for Government, there’s every reason to be a little optimistic.

There are several other European countries that have already implemented a right to housing- Spain, Sweden, and the Netherlands, to name a few. All of which have better social housing and fewer homeless people than Ireland.

And if our European neighbours aren’t reason enough to implement a right to housing, the 10,000 homeless people in Ireland are. Ireland has tried one system for long enough. It might be time to try something new.

Elsewhere on District: Sharp increase in Dublin landlords reported for damp, mould and rotting floors