How surrendering to the supernatural inspired Villagers’ new album

Words: Dylan Murphy

Photography: Ellius Grace

Illustrations: Conor O’Brien

Clothing: Indigo & Cloth

Ahead of the release of the stunning Fever Dreams, Conor O’Brien of Villagers spoke to Dylan Murphy about how a late night swim under the stars and recurring symbolism gave him a refreshed worldview in increasingly volatile times.

Conor O’Brien is cautiously optimistic. He’s back in Dublin a few days after finally having the opportunity to play to thousands of fans at Latitude Festival. It’s the type of experience he’s been dreaming about since he hunkered down in his city centre apartment in March of last year but one that has still eluded Ireland.

The Mercury Prize-nominated songwriter and brain behind Villagers has spent the better part of a decade making otherworldly records that swim in the abstract. The kind that unwinds slowly, offering food for thought for curious minds, and immersive soundscapes for escapists. This is particularly convenient for restless listeners, given that most responses to the pandemic have been defined by dissociation or periods of existentialism.

Caveats

While you’d think the ultimate reward for soundtracking countless people’s time in confinement would be belting out the lyrics in front of a sea of fans, like every forward step in the past year, it has been met with a caveat. Sat comfortably in a chair opposite a third-floor window overlooking the quays, Conor explains that for every first-gig-back guitar-fuelled adrenaline rush, there’s a tensed forehead focused on reconnecting with playing live. For every long-awaited hug, there’s a chance of catching Covid and jeopardising shows that have been put on hold for over 500 days. These very tangible risks have been compounded by an increased sense of pessimism bred by the last year and a half. We’ve been conditioned to live on the edge, to not get our hopes up, to be wary of the next glitch in the matrix that reminds us we’re just one 2021 bingo card away from the next absurdity. Even the most hopeful artist can’t afford to be careless.

In the midst of this cocktail of conflicting emotions, the Villagers frontman found solace in literature and returning to visual art. He joined a weekly life drawing class on Zoom hosted by his friend in Berlin and sought to make sense of the big questions by immersing himself in decades-old literature that still held up to today’s scrutiny.

Meanwhile, luckily for the singer, he had the bulk of his album completed right before lockdown. It meant in between chapters and trying to understand increasing online tribalism he could fix the tiny details of the record.

“I’ve got a tiny little attic studio which I could work the stuff through, it kind of saved me during lockdown cause I would’ve went insane if we didn’t finish the band stuff. It was perfect timing in a truly ego-centric way”, he explains.

However, outside of the music, he still needed artwork for his new album Fever Dream. While he’d got back into drawing again, his creative skills weren’t translating as he would have liked them to when it came to the cover art.

“I was trying to do the artwork myself and I was failing, I just couldn’t draw and I was blanking completely and getting frustrated. I knew it had to be something to do with scale. A lot of the album’s warbly lo-fi bits sound really intimate and close and then suddenly you are out in space and it is really cosmic”, he says with his hands pulsing in and out, “I really wanted the artwork to represent that without feeling too science-fictiony”.

In turning to another designer he was met by one in a number of coincidences that became the album’s symbolic glue.

I became obsessed with the number seven for a year and a half and I was just seeing it everywhere.

Conor O’Brien, Villagers

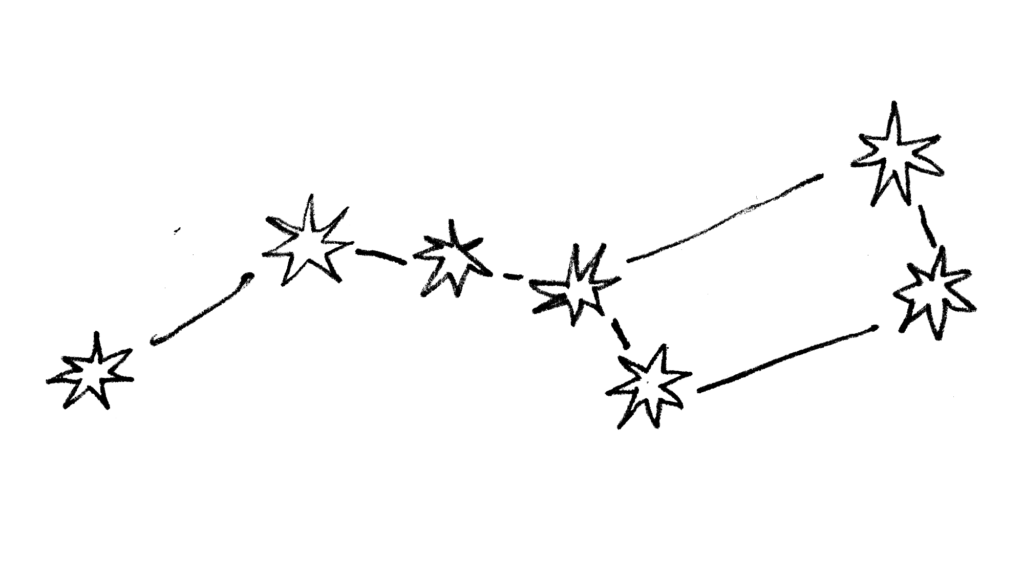

“[The designer] his stuff reminded me of old ‘Judge Dredd 2000 AD’ stuff which again is kind of sci-fi vibes, I just got onto him, and I wasn’t sure he’d be the right guy for the job but I sent him two or three songs and he sent me the bear and the guy in the pool,” he says. “I was instantly blown away and I sent him an email back being like ‘aw man Ursa Major is in one of the songs’. He was like ‘oh that’s a cool coincidence’ and then we started teasing out maybe doing four album covers and the constellation idea picked up more and more.”

Leaning forward in his chair and fixing the lapels of his blue shirt, Conor explains that the appearance of the constellation in a song and in the cover art was one in a number of the album’s overlapping coincidences.

“It’s weird, I became obsessed with the number seven for a year and a half and I was just seeing it everywhere. After a while, I was like ‘I don’t think I’m looking for this anymore’”.

Ursa Major

“The main asterism of Ursa major was the seven stars. We were swimming after a show in Holland and Brendan pointed at the sky and was like ‘look, it’s Ursa major!’. We were all kind of tripping out looking at the sky, swimming in this really warm water and I was just like ‘oh my god, that’s the number seven again’. I had this recording of Danny, the bass player playing a song backstage in Galway a few weeks before that, he’s a jazzer and he was like ‘are you writing a song in seven?’ and I was like ‘oh my god it is in seven’. The number seven just kept appearing.”

Having been initially startled by the recurring presence of the number, Conor eventually surrendered to the phenomena with the results being crystallised in ‘Song in Seven’ from the album. The symbolism, the experience of swimming under the stars and even the recording of Danny can be heard throughout the track, providing an exaggerated motif of his obsession.

“Seven days a week, moon cycles, it’s in nature quite often and I just find it interesting. If you get obsessed with something that seems like it’s not worth focusing on it’s a good doorway into a lot of other themes. I think that number was my doorway, I was looking around the album through the heptagon prism.”

In a time of uncertainty, the seemingly arbitrary appearance of the number in his life and obsession with sights beyond our own earthly confines appeared to bring a sense of wonder and spontaneity to an increasingly predictable world. One where our days indoors were mapped out to the finest detail and premeditated coffee runs and daily walks were the height of recreational activity.

Conor even admits that the mixing decisions were done in multiples of seven. With the panning and volume numbers ranging between 7, 14 and 21 throughout the album. Cracking a smile so big it shone through his mask, he concedes it’s a result of “lockdown craziness” more than anything else.

Dreams

As the album took on a life of its own and became an expedition led by mystic powers, Conor further expanded its reach by inviting fans into its universe. In the three weeks leading up to the album release, Conor hand drew a “dream portrait” once every seven days based on descriptions sent in by fans.

These “dreams” could be anything from actual dreams they’d had at night in their sleep or aspirations for their own lives. It’s his way of bringing things that have lived only in their minds into the physical world during a time that has been defined by virtual interactions.

“It’s cool, I got such a weird variety of paragraphs about crazy stuff and some really moving stuff – even people dreaming about people coming back from the dead” he says slowly, describing their personal experiences with the careful attention of a father holding a newborn child.

It’s this intersection of art, technology and shared experience that gives Conor optimism in spite of an increasingly divisive digital landscape too.

“I found literature in the last two years to be mind-bendingly important for me personally”, he says crossing his legs and fixing his posture on the office chair.

“I feel as though there is a lot of tribalism going on and people thinking in binary ways and even if they think they are being progressive, they are actually really conservative and I think the internet is to blame” he says before inserting a disclaimer that it’s more of a gloomy observation rather than a scornful rant.

Maybe it can’t solve all the world’s problems, but burying himself in time-consuming practices at least gave him reason to be cautiously optimistic.

“There is a lot of reactionary thought happening and I think music and art might have something to play in the fight against that.”